Caleys Business

Published in Windlesora 23 (2007)

© WLHG

Caleys store in Windsor High Street closed at 6pm on Saturday 15th July 2006, 183 years after the Caley family first moved into the shop.

Maria Caley founded a business sometime before 1813. Her first shop was in Thames Street where shops lined both side of the street. She then moved to Castle Street, now Castle Hill, roughly where Queen Victoria’s statue stands today, and the shop was about 30ft from the walls of the castle In 1823 her brother, John William (the first of that name), ‘a silk mercer and laceman’, moved the business to the High Street.

Over the years there were several rival firms all within a short distance. Messrs Bird and Alien were at 25 High Street, Richard Sharman and Harry Cook traded near by in Park Street, a Miss Lloyd traded as a milliner and described her merchandise as ‘fresh from Paris’. Perhaps the best known was the firm of Rodgers and Denyer also dress makers and milliners to the court. This was where author H G Wells was apprenticed in 1880; the heroes of Kipps and History of Mr Polly were both drapers’ assistants. Caleys was to prove the most successful of the businesses.

In 1845, John William, son of John William the first, Maria’s nephew, joined the business which became Caley and Son, and when Frederick Goodman Caley also joined it became Caley Brothers.

By the 1870s the business was run by Hugh A Caley, son of Frederick, and further expanded. He and his wife had an unerring instinct of enterprise and tradition. Mrs Hugh Caley was in fact a remarkable successor to the founder; Mr Robinson, a Caleys employee, paints a picture of her queening it in the gown showroom and correcting in serene self-possession a noble customer’s memory: ‘It was in such and such a year that your ladyship wore that particular dress’. Mrs Caley kept her own documentation of every model served to regular customers.

The family was very religious and worshipped at the Gospel Hall in Windsor, a sect very similar to Plymouth Brethren today, strict and evangelical. When tramps were evicted from the Guildhall porch they were given shelter in the railway arcades which John Caley lined with straw, and they provided buns, tea and hymn singing. John William junior was a member of the Early Closing Association and in 1853 we find him seconding a motion urging all traders to follow the example of the drapers and close their shops at 8 pm during the months of April to September, and 7 pm during the winter.

When the American evangelists Sankey and Moody were unable to get permission to organise a revivalist meeting in 1875 Frederick Goodman Caley, who lived in on his shop premises, seeing that there were crowds in the High Street, offered his large garden at the rear and this was accepted. Customers and about 300 Eton boys entered through the shop whilst others entered from Acre Passage. A choir of 30 and a congregation of about 1,000 heard the sermon of Mr Moody, as he stood on a chair under a chestnut tree.*

Royal Patronage

Royal warrants are granted only after a business has provided goods or services to a Royal household for a number of years. Queen Elizabeth II is the seventh queen on whose account Caleys have held a royal warrant, the first being Queen Charlotte, wife of George III, who died in 1818. By 1900 there were 22 warrants including the Empress of Russia, Prince Henry of Prussia and the Crown Princess of Greece among others.

Although Queen Victoria never entered the store, she had a close association with it. Every one of her bonnets was made in the millinery department. White bonnets were for morning wear, black bonnets sequinned were for evenings. The head milliner, a Miss Coles in the later 19th century, went regularly to the castle. A black bonnet worn by Queen Victoria was displayed in a case outside the coffee shop until the firm closed.

One of the charitable events of the town took place on Christmas day when the Queen’s Bounty was distributed to the poor, the local tradesmen contracting to supply the food, with Mr Caley supplying blankets, flannelsand cloaks. In 1847 blankets were stamped ‘The gift of HM the Queen and HRH Prince Albert’.

The Queen did more business with Caleys in 1868 when she purchased a quantity of green damask for the green drawing room, in preparation for the marriage of the Princess Royal. This was one of the rooms destroyed in the 1992 fire and now beautifully restored. They also supplied the wedding trousseau for the marriage of Princess Alice to the Grand Duke of Hesse, and the gloves for Princess Alexandra’s wedding in 1863.

The swathed toques of Queen Mary, consort of George V, were supplied by Caleys. At John Lewis’ archives in Stevenage, they have a blue toque with an interesting story. It was supplied with other hats on approval and after a while all were returned. However, during the period of time the hats were at the Castle a photograph of the Queen wearing the blue hat was spotted in a newspaper.

After the fire in 1992 Caleys were asked to provide wallpaper and fabrics for the staff rooms in the Brunswick Tower and blinds for the Prince of Wales Tower, 2700 feet of wallpaper and 300 metres of fabric for bedspreads, furniture covers and curtains.

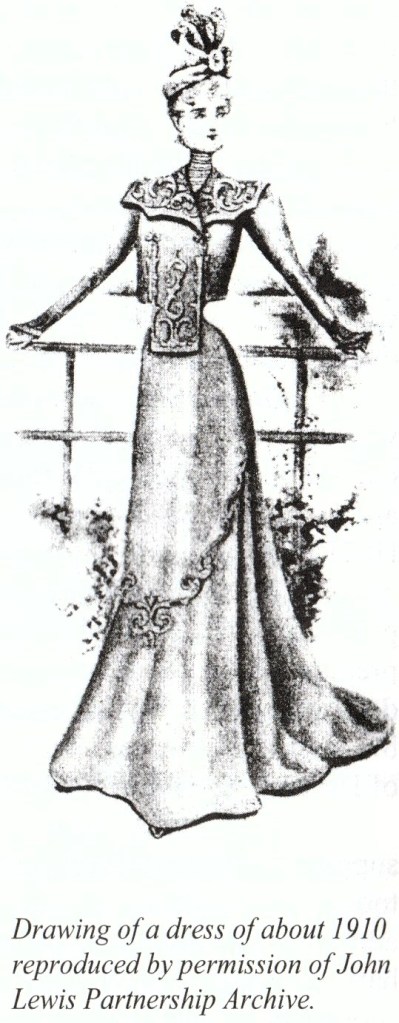

The shop in the High Street was continually expanding, keeping with every vogue and the current social trends. Dressmaking and millinery were the most important constituents of the business at a time when ready-to-wear garments for women were virtually unheard of until well into the 19th century.

The emphasis was on quality trade, dignity and restraint. Opulence and security were reflected in the deep-carpeted showrooms, with products from France and Switzerland as well as home produced goods.

Each year the Caley family let out their house in Osborne Road whilst they travelled abroad accompanied by the head milliner and the head of the gown showroom. Soon, huge wooden crates filled with model gowns would arrive from Paris. As soon as these were unpacked mannequins would walk the showrooms in them and a woman artist would make sketches and then finished paintings, which were eventually hung along the walls. Every presentation gown made by Caleys was displayed in the shop.

Mrs Caley took advantage of the fact that women were beginning to read newspapers. She had advertising campaigns especially to advertise the Spring and Autumn new fashions. The shop kept up to date with changes in fashion and materials, electricity, telephone and other mod cons as they became available.

The packing of gowns was an art. Each was draped in immaculate folds of tissue paper and a gold-edged card bearing the name of the debutante who was to wear it was included. It was delivered in a special Court ‘train box’ made of wood, to ensure that the garment could travel any distance and arrive without a crease. If it was going abroad it was packed in tin and then roped and sealed.

Caleys was an acknowledged shop of wealth and fashion. Day after day the carriages drew up, the steps were lowered and a commissionaire escorted customers to the door. The fashionable hours for shopping were from 11.00 to 1.00 in the morning and 3.00 to 4.00 in the afternoon. Accounts were sent to established customers twice-yearly midsummer and Christmas, with 5% interest being charged on anything outstanding after 6 months. However it was a business that needed profit and sales were advertised. For example in 1862 the public were told ‘As a result of improvements a large portion of remaining stock is available at a considerably reduced price – 22% for ready money’.

Funerals

Caleys became funeral furnishers by the 1860s. In 1862 they advertised their new coffins:

Wood coffins entirely superseded and lead ones rendered unnecessary by the use of this patent air tight metallic coffin which combines all the advantages of a wood, shell, lead and oak coffins. In addition to the economy of these coffins their great advantage is that no matter what the cause of death or however infectious the disease there can be no possibility of danger to the relatives or inmates of the house from the escape of noxious effluvia.

Many drapers began conducting of funerals to ensure good business for their mourning department. It was a worthwhile business when a lady’s dress required 10 or 12 yards of material and full mourning was worn for weeks after.

Gown Workshop

Caleys had their own gown workshop as early as 1851 with a staff of 89, roughly the same number as those that worked in the shop. Before that the work had been done in a corner of the drawing room when the family lived above the shop. As the shop grew so did the workshop and by 1907 there were 105 working there. The making of Edwardian clothes was complicated, time consuming and labour intensive. Labour was cheap; hours were long. Staff worked from 6.30 am to 8 pm on weekdays and 4 pm on Saturdays. The total wage bill for 1907 was £2420 which gives an average of 44p for each assistant per week. Skilled fitters or cutters earned more and apprentices might get no cash payments at all. No overtime, no bonus, and they often had to stay to finish garments to meet a delivery date.

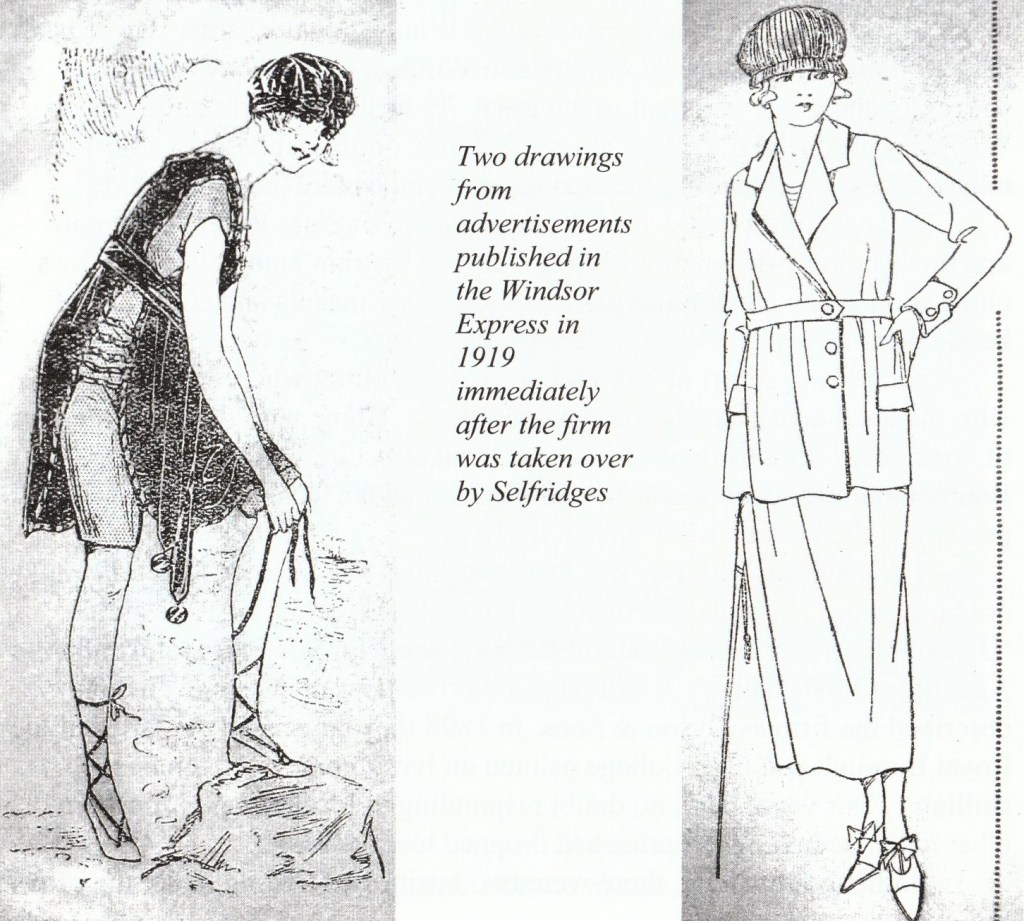

The setting up of Government Trade Boards for the needle trades between 1912 and 1920 gradually ensured standardisation and improvement. This inevitably involved extra costs and coupled with various social changes such as the increasing availability and acceptability of ready-to-wear clothes and the direct and indirect effects of WW1 led to a decline in the scale of fashion workshop operations. The vast armies of seamstresses and milliners who had once toiled behind the scenes were dispersed.

Deliveries

Mr Archibald Robinson started work in the Despatch Department of Caleys in 1897 and retired in 1947. Costumes and gowns were packed for delivery in wooden boxes, and with one of these in hand he tramped for miles round the district and thought nothing of setting out for a circuit on foot of Eton College, Eton Wick, Dorney, Slough and Datchet.

The gowns were packed in geographical order, that is, the further away the destination the nearer the bottom they were placed. At house after house the box was opened and the customer or her attendant was requested to remove her gown from the top of the pile. The same rule applied for the packing of bonnets and hats in wooden hatboxes of the familiar oval shape.

Mr Hugh Caley later bought a modern safety-type bicycle with pneumatic tyres. Having tested it out for its potentialities for himself, he began lending it for business use to Mr Robinson who was probably the first man to deliver goods on a bicycle in Windsor.

In 1909 Caleys was at the peak of their success. Their letter heading described them as Court Dressmakers, Mantle Makers, Milliners, Ladies’ Tailors, Silk Mercers and Linen Drapers, Ladies and Children’s Outfitters, House Furnishers and Upholsterers, and Funeral Furnishers. They also had a lease on 18 Albemarle Street Piccadilly London ,carrying on a business as Court Dressmakers.

The End of Caleys as a Family Business

On the 26th May 1909 the family business was incorporated with three directors, Hugh Caley, his wife Anne, and retired chartered accountant A G Blow. Hugh Caley sold the business to the Company for £24,000 including £15,306 for furniture, horses, stock etc, £2,815 for goodwill and including the business in Albemarle Street.

In 1919 the American, H Gordon Selfridge, who had founded the Oxford Street store ten years earlier, was looking to expand into the provinces. No member of the Caley family was interested in running the business so they decided to sell.

In 1940 the Selfridge family sold the whole of the Selfridge Provincial Stores to the John Lewis Partnership. Over the following years the shop extended into adjoining premises and in 1951-2 the High Street frontage was rebuilt in approved Georgian Style.

The store was an amalgam of five-and-a-half High Street buildings, several of them listed. There were 24 different floor levels so that lifts and escalators were not feasible. There was no space for large sized merchandise and storage was limited, every inch counted.

This building has considerable charm and was a unique place in which to shop. The Georgian facade has wrought iron balconies, which in summer were festooned with flowers. Inside there is a staircase protected by a preservation order, acanthus topped columns, which rise to the ceiling in the perfumery department, two mediaeval wells and at least two ghosts.

Windsor will not be the same without it and I am sure we all approach whatever changes are to come, with great trepidation.

Norman Oxley

Notes

*Full details in an article “Rival of Moody and Sankey in Windsor” by Fred Fuzzens in Windlesora No 7.