Published in Berkshire Old and New 33 (2016) and Windlesora 34 (2018)

©2016

During the early nineteenth century, most British regiments introduced regular medical inspections for venereal disease. These so-called willy-parades were highly unpopular. In 1845 two soldiers of the Coldstream Guards stationed in Windsor, who had refused to strip in front of their comrades, were court-martialled on the spot and received 100 lashes each. The whole proceeding, including the court martial, took only two and a half hours.(¹) It not only highlighted the problem of venereal disease in the army, but also showed individuals’ modesty about displaying their naked bodies in front of comrades. The case was consequently discussed in Parliament. Thomas Wakley, member for Finsbury, asked the Secretary at War, Sidney Herbert, why soldiers had to strip in front of a whole company, for the purpose of being examined by a surgeon.(²) William Williams, member for Coventry, added that ‘nothing could be more indelicate or indecent or more repulsive to a proper and correct feeling, than to be placed under the necessity of undergoing such an examination naked in the presence of a large company of their comrades’.(³) Admiral Dundas, member for Greenwich, then said that ‘from his experience, it has never been customary for soldiers or sailors to strip together, in front of each other’.(⁴) This ‘modesty’ explains to some extent the ability of women to get away with serving in the forces disguised as men until well into the 1820s, when more stringent medical examinations were introduced.

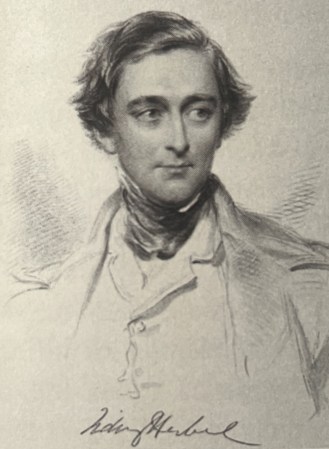

Sidney Herbert (⁵) explained that many of the Guards in Windsor were affected with a certain disease, that many tried to conceal this fact, and that the authorities had ordered a rigid examination, as the result of which sixteen men were found to be infected.(⁶) Medical examinations remained controversial and unpopular with both soldiers and doctors. John Trotter, assistant surgeon of the Coldstream Guards was said to have examined 500 – 600 men in half an hour, which could not have been a thorough examination.(⁷) Eventually, some commanding officers dispensed with them altogether. In 1858, Dr Logie, surgeon of the Royal Horse Guards, lamented the fact that the commanding officer had thought it necessary to do away with the weekly health inspection, ‘as it excited such dissatisfaction’. Now the only means for detecting venereal disease was the inspection of prisoners, of soldiers in hospital and of men coming off furlough.(⁸) By 1859, compulsory inspections of troops were abolished.

Acton claimed that ‘about one in three soldiers suffer from some sort of venereal complaint’,(⁹) and Blanco stated that in 1859, 422 admissions to the army hospital out of every 1,000 were due to venereal disease.(¹⁰) The Army Medical Department’s returns for venereal admissions into hospital show a much higher rate of venereal disease in the Foot Guards and the infantry of the line than in the Household Cavalry. This may be due to the fact that a much higher percentage of cavalry soldiers were married.

These figures clearly worried the authorities, and as soldiers would not be examined the alternative was to examine and treat the prostitutes in order to provide clean and healthy women for the troops.

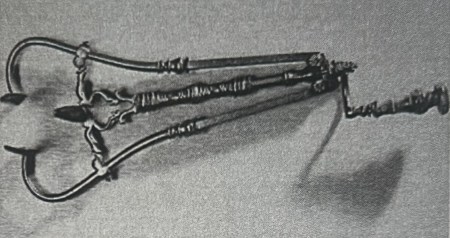

The first attempt by Parliament to curb prostitution was the Seduction and Prostitution Bill, which was passed in 1847.(¹¹) Mr Roebuck, member for Bath, commented ‘The House in passing this Bill were travelling out of the real province of legislation into the province of simple morality, and they were attempting by legislative interference to bring about that which no mere law could ever effect’.(¹²) Lord Brougham objected to the Bill by pointing out that ‘the vilest prostitute could get a man imprisoned for a long period’.(¹³) The Contagious Diseases Acts which were introduced in 1864 had a different aim, which was not so much to curb prostitution as to make paid sex safer for the troops. However, they put the whole burden on the prostitutes. The Act of 1864 was applied in the naval and garrison towns of Portsmouth, Plymouth, Southampton, Chatham, Sheerness, Aldershot, Colchester, Woolwich, Cork and Queenstown. Under the Act, any woman identified as a prostitute by a constable could be forcibly examined, and if found diseased, taken to a government lock hospital, which specialized in the treatment of venereal disease, where she could remain for several months, and where the ‘cure’ for syphilis was mercury!

The Contagious Diseases Bill of 1866 was read for a second time in the House on 15 March, with a view to widening its application to include Windsor with Eton and Clewer. There was very little discussion of the Bill, and a Select Committee was appointed consisting of nineteen members with a quorum of five to discuss the Bill in private. Only two members expressed concern. Mr J. W. Henley, member for Oxfordshire, said that ‘the measure was a very queer Bill upon a very queer subject’. Its object was to preserve the health of Her Majesty’s troops, and its endeavour was to remove all the penalties, which a higher Power had imposed upon sin, and to give the opportunity of sin without the punishment. He asked the Chancellor of the Exchequer if he could ‘expect any blessing upon their legislation if they took these unhappy women, freed them from disease, and then turned them loose to follow the same wretched course, without any attempt to reclaim them’.(¹⁴) Mr Ayrton, member for Tower Hamlets, who two years ago had opposed the Bill for just this reason, viz. it made no provision for reclaiming the unfortunate women, now wanted to know why Windsor was included in the Bill but not Westminster.(¹⁵) Sir George Grey, Secretary of State for the Home Department, replied that the Bill applied to places where either of the services constituted a considerable portion of the population within a five-mile radius of this town.(¹⁶) The Bill was twice referred to in the House, in June and July, but there was no debate in Parliament, and on 29 July 1866 it received the Royal Assent.(¹⁷) The Windsor and Eton Express was equally reticent about this Bill, which was to affect the town. It was never mentioned throughout its early existence and passage through Parliament, and not until February 1868, when the Act came into force in Windsor, did this article appear in the paper:

The Contagious Diseases Act. – It has been resolved by the military authorities to apply the provisions of the Contagious Diseases Act to Windsor, Colchester, Shorncliffe, Canterbury and the Curragh, the London Gazette on Tuesday published this notification dated from the War Office February 11th: “The Secretary of State for War has appointed E. Pearl, Esq., to be visiting surgeon for Windsor, under the Contagious Diseases Act 1866.” (¹⁸)

The Act was overseen by the War Office and the Admiralty, but passed by Parliament; however, the newspaper put the onus for this legislation on the military, leading most unsuspecting readers to believe it was military legislation. There was no further discussion of the Contagious Diseases Acts in the paper; even prostitution was not reported on as it had been in the 1840s and 1850s. But there must have been some local debate about the Contagious Diseases Acts and their implications for Windsor. Claude Quétel quotes:

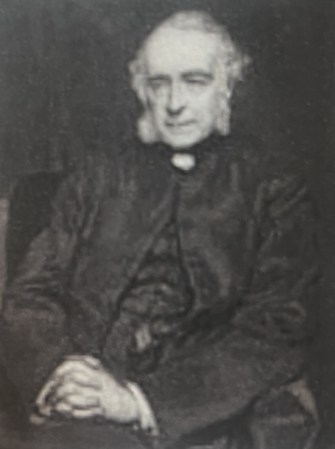

The new legislation, said the vicar of Windsor, treats fornication as a necessity, since its aim is to render the practice less dangerous, the result of this is that men can sin in greater physical security and abandon themselves unrestrainedly to their whims.(¹⁹)

Unfortunately, he does not reveal his source. The vicar of Windsor, who must have been the Revd H. J. Ellison, clearly recognized that the Acts gave the military a false sense of security and conveniently released them from any responsibility of keeping soldiers free from venereal disease. There were also a number of soldiers who felt insulted by the Acts. Trustram quotes:

there is a section of the rank and file who would protest vehemently against the Acts as a libel on their character, and fully expose the Government who proclaim by these laws to our fathers, brothers, mothers and sisters that we have become so debased in an honourable profession as to require a certain number of working men’s daughters to be sacrificed in perpetuity, by special legislation to preserve our health.(²⁰)

The fact that the 1866 Contagious Diseases Act had been invoked in Windsor is a clear indication that prostitution and venereal disease were major problems, but this was no longer discussed openly. It is also much more difficult to identify prostitutes who came before the magistrate. The women who appeared before the Windsor magistrate, charged with drunk and disorderly behaviour, using obscene language or loitering, were not described as prostitutes, as they had been in the past.

Neither was there any mention of the government lock hospital which every garrison town that came under the Contagious Diseases Acts was obliged to set up to accommodate diseased prostitutes. No records have survived, and the memory of this hospital seems to have been lost in Windsor. Only one mention of the government lock hospital can be found in the unpublished autobiography of a cavalry soldier who wrote: ‘There had also been, in Alma Road, a lock hospital, made over to the Imperial Services College, though not for the same purpose’.(²¹) This at least gives us an indication of where the hospital was.

Before a lock hospital was built, the workhouse infirmary took patients with venereal disease. Few records for the Windsor workhouse have survived, but a report of 1867 on the workhouse infirmary published in the newspaper states that there were two small separate buildings at the back of the infirmary for venereal patients. The women’s ward was described as uncomfortably full, and the men’s ward was even worse. There was a foul stench, even though doors and windows were wide open. ‘The children’s ward is near that of fallen women, and they have to pass through it to get to their own’.(²²)

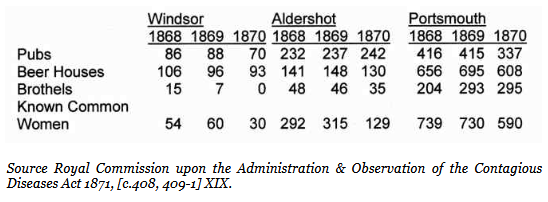

The only surviving facts concerning the Contagious Diseases Acts as applied to Windsor are contained in the report of the Royal Commission upon the Administration and Observation of the Contagious Diseases Act of 1871, which tried to justify the Acts and prove their success by showing a decrease in prostitutes, brothels and public houses (table below). Each town also took in a five-mile radius; therefore figures for Windsor not only included Eton and Clewer but also Datchet and Old Windsor.

In 1869, the Ladies National Association was established to fight, among other injustices to women, against the Contagious Diseases Acts. It was spearheaded by Josephine Butler who was able to disprove the above figures; she was also able to prove that prostitution and venereal disease had not declined. A manifesto the Ladies National Association took to Parliament included the sentence: ‘it is unjust to punish the sex who are the victim of a vice, and leave unpunished the sex who are the main cause’.

The campaign was successful. The Contagious Diseases Acts were repealed in 1886, and willy-parades were reintroduced in the army.

Brigitte Mitchell

References

Windsor and Eton Express [WEE] 19 July 1845.

- Hansard, LXXXII, 18 July 1845, c.674-677.

- Ibid., c.676.

- Ibid., c.677.

- The Right Hon. S. Herbert, 1810-1861, MP for Wiltshire South, Secretary at War 1845-6, 1852-4 and Secretary of State for War 1859-61.

- Hansard, LXXXII, 18 July 1845, c.676.

- Myna Trustram, ‘Marriage and the Victorian Army at Home; The Regulation of Soldiers‘ Relationships with Women and the Treatment of Soldiers’ Wives’ (University of Bristol. PhD thesis 1981) p. 144.

- Royal Horse Guards, Medical Officers’ Correspondence, Annual Report of the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards from 1 April 1857 to 31 March 1858 at Windsor.

- William Acton, Prostitution (1968) p. 78.

- R. L. Blanco, ‘The Attempted Control of Venereal Disease in the Army of Mid Victorian England’, Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, v. 45 (1967) p. 236.

- Hansard, XCIV, 23 June 1847, c.811.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. 13 July 1847, c.215.

- Hansard, CLXXXII, 22 March 1866, c.815.

- Ibid, 22 April 1866, c.2177.

- Ibid.

- Vict. c. 85.

- WEE, 15 February 1868.

- C. Quétel, History of Syphilis (1990) p. 235.

- Trustram Women, p. 132, from National League Journal, 1 September 1875, p.13.

- R. J. T. Hill, Horse Foot and Guns, unpublished and unclassified manuscript, Household Cavalry Museum Archives, p. 162.

- WEE, 5 October 1867 and 2 November 1867.

Berkshire Old and New

Members of the WLHG regularly contribute to the Berkshire Old and New magazine published by the Berkshire Local History Organisation. The WLHG is also a member. These magazines are freely available and contain a rich source of information about the history of Berkshire.