Windsor barracks in the early 19th century

Published in Windlesora 24 (2008)

©WLHG

The first buildings of any note to be constructed in Windsor since the building of the Guildhall [1687-1689] were the two barracks. Why were two large barracks built in a small town like Windsor, turning it into a major garrison town?

During the Napoleonic wars, the Government had to find sites for a total of 203 barracks. Windsor, which had only recently regained royal patronage under George III, and had once more become a major royal residence, needed protection. George III was also keen to bring his favourite regiment the Royal Horse Guards, affectionately known as the Blues, to Windsor.

A small garrison had always been kept in Windsor, quartered mainly in the inns and public houses of the town, and more recently in the guardhouse built by Charles II in the Middle Ward, backing onto St George’s Chapel. [This was pulled down during the 1820s.]

The two new barracks planned for Windsor were Infantry Barracks in Sheet Street, and Cavalry Barracks in Spital. The Infantry Barracks were built between 1798 and 1799 on a site of one acre, next to the old poorhouse. They were designed for 750 infantry soldiers. Mr E Pinnock sold the land, which used to be an orchard, for £1,260. In 1803, an additional building was planned to provide a canteen with kitchens, bake-house, parlour, bar, tap-room, sergeants’ rooms and bedrooms for 100 men, at a cost of £925.(1) In fact infantry soldiers had to wait for such comforts for several more decades. The planned building simply became an extra barrack block for a further 250 soldiers. Housing 1,000 soldiers often accompanied by several hundred women and children in such a small space was made possible by the use of wooden bunks arranged in two, sometimes three tiers, with two men per bunk. Of course, such overcrowding had a damaging effect on the health of the soldiers and their families who were regularly crammed into these buildings.

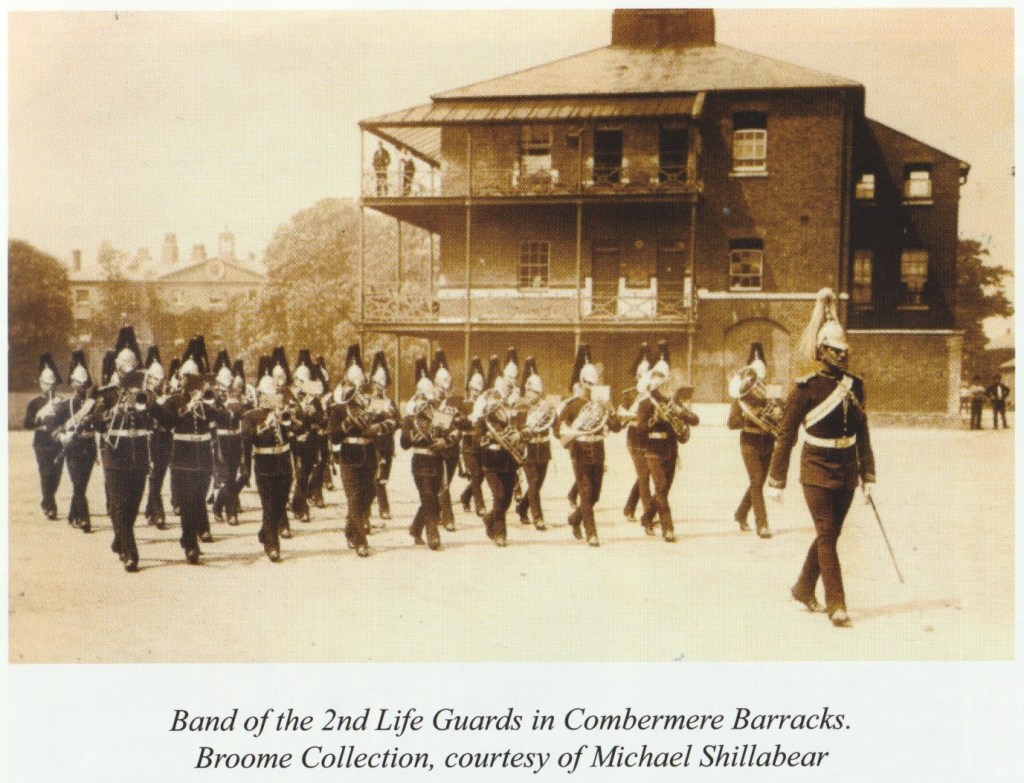

The Cavalry Barracks were built some way out of town in Clewer, along the Spital Road [St Leonard’s Road] on fourteen acres acquired from Mr S Round. They were built between 1800 and 1805 on a much larger scale than the Infantry Barracks, to house about 450 men and their horses. The accommodation for the men was above the stables, as in all cavalry barracks of the time. The horses provided extra warmth in winter, but the combined smell of barrack room and stable must have been potent.

Charles Knight senior describes the new buildings in the Windsor Guide of 1811:

‘The system which had been adopted by administration, partly to relieve the publicans from their burthen of quartering soldiers, and partly to concentrate the military force, was carried into effect at Windsor in 1795, by the erection of handsome and commodious barracks, in a part of town called Sheet-street, for the accommodation of 750 infantry. In 1803 an additional building was erected at the south end. These buildings are well constructed and have a grand appearance, but are in a situation too flat and confined.

Situated at about half a mile from the town, on the road to Winkfield, is also a very handsome building; and, although the structure, in point of inagnitude, is inferior to the Infantry Barracks, yet from the open and judicious disposition of the whole, it has a more pleasing appearance; it will contain He hundred horse, with all requisite accommodation for officers and men.(2)

A survey of 1847 shows that the two barracks between them housed 1,214 men(3) the reality was that they were often seriously overcrowded and in addition to the soldiers, there were the women and children who shared the quarters of the soldiers. During the 1820s the bunks were phased out and iron bedsteads introduced to combat overcrowding, but Wellington lamented that ‘the use of single iron bedsteads has diminished the number, in almost every barrack’.(4)

The Duke’s negative influence on the improvement of the common soldier’s life and conditions was to continue for another fifteen years, to the detriment of the soldiers’ health and well-being. Iron bedsteads reduced the official capacity of the Windsor Infantry Barracks from 1,000 to 790 men.(5) But these regulations were largely ignored, and beds were simply moved closer together giving the men even less space to move around. One must not forget that the barrack room was the only living space soldiers and their families had.

The 1847 Returns for each Barracks in the U.K. furnishes us with a first insight into the conditions in the Windsor garrison. It highlights the lack of washing and cooking facilities, and gives an idea of the size and recommended capacity of the barracks. These returns were not discussed or commented on in Parliament, although they were part of a wider concern and inquiry into the poor health and high mortality and sickness rate of soldiers. Spending on barracks was not popular; when Parliament pronounced in 1843 that it had spent two million pounds on barracks since 1826 it was declared a ‘monstrous outlay’ since it made soldiers more comfortable than the working class.(6)

In the Windsor Infantry Barracks up to 29 men slept in one room measuring 50 feet by 22 feet; each room had just one fireplace and one window. Each room officially also included a soldier’s family. However, these figures cannot be relied on, and it is notoriously difficult to identify the women and children in the barracks, but there is enough evidence to show (hat they were there in large numbers. The rooms in the Cavalry Barracks, measuring 28 feet by 16 feet held nine soldiers. Smaller rooms were for NCOs. In these crowded conditions men, women and children had to sleep, cook their food on the open fireplace and eat it, wash their clothes and dry them; soldiers cleaned their kit, gambled, drank, swore, suffered and died; children were born, grew up and often joined the regiment as boy soldiers or soldiers’ wives.

Each soldier was given two sheets, two blankets, palliasses and bolsters. One roller towel per week had to do for eight cavalry men or twelve infantrymen. In the same way eight cavalry soldiers received two and a half pounds of candles per week, whereas twelve infantry soldiers had to make do with one and a half pounds. Washing of sheets took place once a month, of towels once a week. Bedding was straw which was changed every 30 days.(7)

In 1854 a Parliamentary Report on Barrack Accommodation condemned the two Windsor barracks as unhealthy, overcrowded and having uppalling sanitary arrangements. The privies in the basement had no seats or doors. Cavalry soldiers washed in stable buckets, infantry men in wooden tubs which served as urinals at night.(8) The fact that privies in the barracks liad no doors or partitions was unusual enough for it to be mentioned in a magistrates’ report in the Windsor and Eton Express, when a soldier stood accused of stealing a watch and chain from a man with whom he had been drinking in the barrack canteen, and who followed him into the ‘conveniences, which are quite open and into which twenty or more persons cun go at the same time.(9)

Although there were a number of Parliamentary inquiries into the state of British barracks and recommendations for ‘urgent’ improvements, it was not until Queen Victoria visited the two Windsor barracks on 3rd December 1864(10) that anything was done. The Queen was accompanied by l’vrincess Helena and Prince Leopold, and they were said to have been shocked by the conditions the Queen’s soldiers lived under. On 28th January 1865 the barracks were inspected with a view to improving the living accommodation of the soldiers, provide married quarters, a new hospital, a canteen and separate stables. Typically Parliament cut corners and improvements were carried out piecemeal, little was done to improve sanitation and in 1872 Dr Logie, the medical officer of the Royal Horse Guards, stated that the Cavalry Barracks were ‘unfit for occupation’.(11)

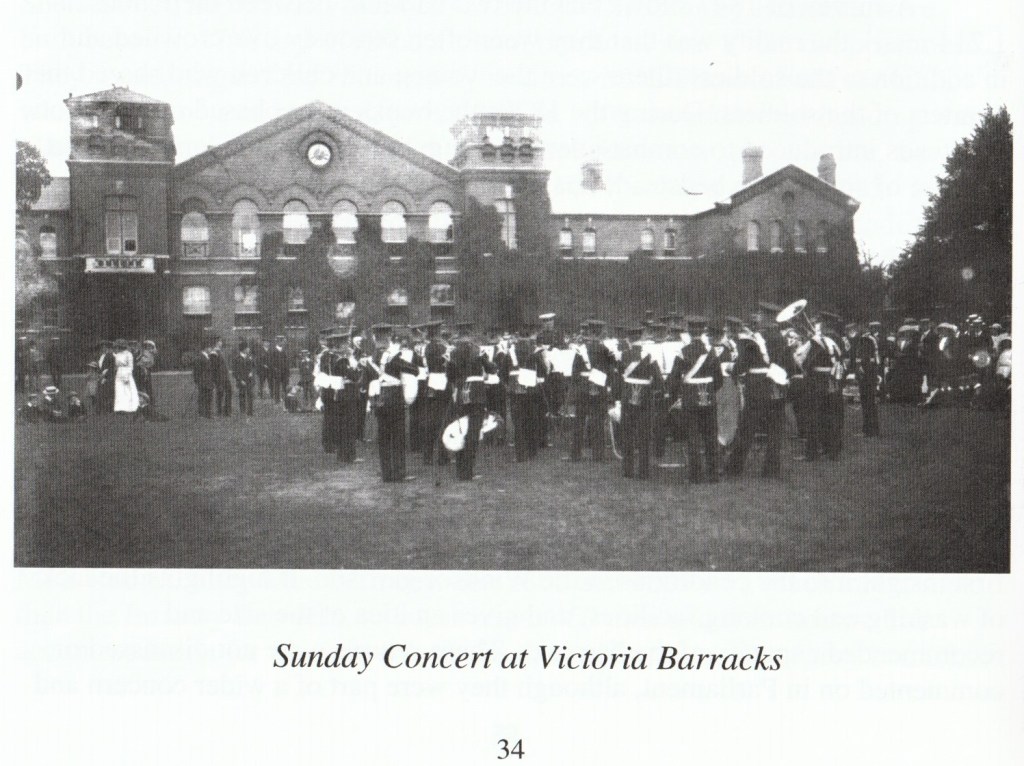

During the 1860s the Infantry Barracks, now called Victoria Barracks, were extensively enlarged over an area called Spring Gardens and again in 1916 a further barrack block was built over Love Lane. The site of the old poorhouse and latterly borough gaol and police station were also incorporated into the barracks, giving infantry soldiers more space. The original 1799 barracks became married quarters and remained so until the 1960s when Broom Farm was developed.

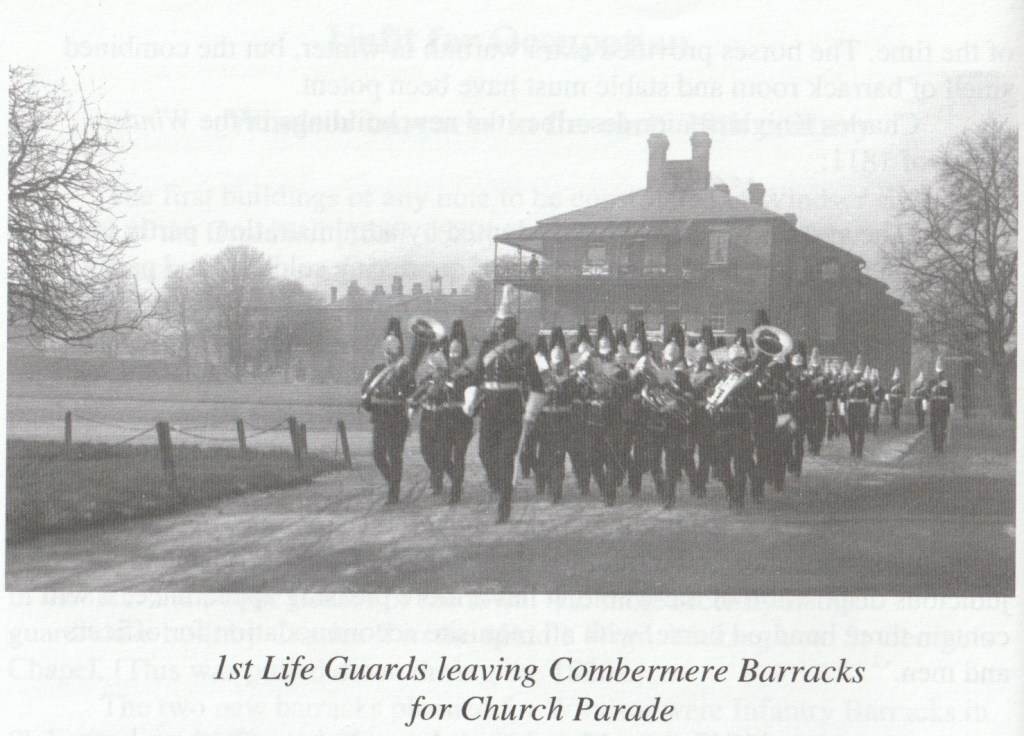

The Cavalry Barracks, now called Combermere Barracks after the Duke of Wellington’s comrade-in-arms, was completely rebuilt during the 1960s and is at present undergoing refurbishment to provide modern soldiers with modern comforts. The old Victoria Barracks have also disappeared; they were rebuilt during the 1980s.

Brigitte Mitchell

References

- PRO, WO 40/18, Plan for Sutling House at Infantry Barracks Windsor, 1803.

- Charles Knight sen., The Windsor Guide 1811, p.25.

- P.P. 1847, Vol XXXVI, Return for each Barracks in the UK, pp. 328-329.

- “Despatches, Correspondence and Memoranda, Arthur Duke of Wellington“, edited by his son the Duke of Wellington, Vol. IV (London, 1865), Regulations Respecting Barracks, 31st Dec. 1827 p.176.

- P.P. 1847, Vol XXXVI, Return for each Barracks in the UK, pp. 328-329

- Hansard LXVII, 1843, c.326.

- General Orders for the Ist Life Guards, 9th July 1837.

- P.P. 1845-55 (405) XXXII Report from the Official Committee on Barrack Accommodation for the Army.

- WEE 31st Oct. 1847.

- WEE 20th December 1864.

- Hansard CCXI, 1872, c.833.