Burnt at the Stake

Published in Windlesora 27 (2011)

© WLHG

Roads have been named after the Windsor Martyrs, and yet how many know the story? It was graphically recorded by John Foxe in his History of the Acts and Monuments of the Church [1563], commonly known as Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. John Marbeck, one of the men implicated, was still alive and had helped Foxe when he was writing of these events of 1543.

The story that Foxe sets out concerns five men: Robert Testwood, Henry Filmer, Anthony Pierson, John Marbeck and Robert Bennett. It must be remembered that Henry VIII lived and died a devout Catholic and would not countenance doctrinal changes. Consequently in 1539 the Act of Six Articles was passed, ‘abolishing diversity in opinions‘ and enforcing belief in six fundamental Catholic doctrines.

It was at this time that the Warden of New College Oxford, Dr John London, became canon of Windsor. Here he was active on behalf of Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, a man who was assiduous in the persecution of ‘heretics‘, that is those questioning long-accepted theology. One of Dr London’s spies was a lawyer, William Simons, who was soon bringing him reports of the priest, Anthony Pierson, who preached in and around Windsor. When Pierson was in the pulpit of Windsor parish church Simons made careful notes of his sermons and stored them up.

Pierson’s unorthodox views were sympathetically received by the church warden, Henry Filmer, a tailor in the town. The vicar of the parish was Sir Thomas Meister whose preaching was approved by Simons although Filmer considered it superstitious nonsense. He reasoned with the vicar and introduced him to new ideas. This alarmed Simons, who succeeded in persuading the weak-willed vicar to complain about the church warden to Dr Capon, the Bishop of Salisbury, in whose diocese Windsor then was. Filmer heard of this and was able to get to Salisbury first. The Bishop listened to him and agreed that what the Vicar was preaching was based on superstition and not on sound doctrine. Moreover Simons was reproved by the Bishop for causing trouble. Simons never forgave Filmer.

Robert Testwood, who had a fine singing voice, was in St George’s choir. He watched the many pilgrims who came to St George’s, and was astonished to see what he considered the encouragement of idolatry in these simple people, but when he expressed himself openly the canons feared loss of offertory money, and Testwood’s scathing comments particularly offended William Simons.

Dr London carried all Simons’ reports back to the Bishop of Winchester, and they agreed that the time had come to halt the subversive undercurrent at work in Windsor. The King was asked to allow for the search and seizure of heretical books and permission was granted. A raid was carried out at 11 o’clock at night on the Thursday before Palm Sunday (16 March 1543), and Filmer and Testwood were arrested for having writings against the Six Articles in their homes, as were a minor lawyer in Windsor, Robert Bennett, and John Marbeck.

Marbeck had been a lay-clerk and in 1541 had become an organist at St George’s chapel. His ability as a musician was acknowledged but he was not a theologian. Yet at his house there were not only writings against the Six Articles but material for a Concordance of the Bible in English – ‘a Worke wherein by the ordre of the letters of the A B C ye maie redely finde any worde conteigned in the whole Bible‘. As he had been engaged in preparing the Concordance for the past six years he had collected a large number of books and papers – too large in the view of the authorities. It became clear in his subsequent examination that Gardiner considered he was incapable of doing research alone and that he must havehad directions from a better- educated sponsor. Gardiner made every effort to discover who this person might be.

After arrest the men were kept over the weekend in custody at Windsor. Testwood was suffering from gout and he was allowed to remain at home in the charge of the bailiffs of the town, but the others were taken to prison in London. Pierson’s arrest must have been at the same time, his later indictment in Court making clear that it was because his preaching was in contravention of the Act of Six Articles.

At the beginning of John Marbeck’s imprisonment in the Marshalsea the conditions were reasonably lenient, but when he continued to insist that he worked on his own and there was no one else to name, the Bishop ordered that he be kept in irons and that no one was to talk to him or visit him – not even his wife. Mistress Marbeck had followed her husband to London, leaving behind in Windsor a 3-month old baby. In desperation she pestered the Bishop until one day she managed to grab his gown as he was passing, forcing him to listen as she pleaded to be allowed a visit. It so happened that at this moment one of the King’s men, Henry Carrike, was passing and heard the Bishop’s vehement refusal. Carrike was the Marbeck’s next door neighbour and he immediately spoke on her behalf, saying that she was a good woman who had her own mother lying bedridden at Windsor besides several children to care for. Finally the Bishop was persuaded to allow Mistress Marbeck to visit her husband but he pressed her to incriminate others and to urge her husband to do so.

On Saturday, 21 July, when they had been in prison for four months, Pierson, Filmer and Marbeck were brought back to gaol in Windsor. Testwood, still suffering from gout, joined them on crutches, but Bennett who was ‘sick of the pestilence‘ was left behind in London.

Woodcut of the trial scene from Foxe’s Book of Martyrs

The trial was arranged for the following Thursday (26 July) and their accusers were so determined to achieve a conviction that they arranged for the jury to be chosen from among St George’s tenant farmers who could be trusted to do as they were told. The prisoners wanted a jury of Windsorians, or at least a jury comprising strangers and local men in equal numbers. This request was refused. There were six judges, led by the Bishop of the diocese, Dr Capon. The indictment against them all was of heresy. They denied the accusations, saying they were either misrepresented or that they had been deliberately slandered.

The case against Henry Filmer is given by Foxe in some detail and is indicative of the sort of story submitted to the court. Henry’s own brother stood up in the witness-box and said that on hearing his brother was going to hear mass one day Henry had said ‘If that be God, I have eaten twenty Gods in my day‘. Henry denied the story and rounded on his brother, a poor labourer, and accused him of accepting bribery. He demanded to see the Book of Statutes under which he was accused and his wife managed to bring it to him. He said if he was to be judged by a law he had the right to see it and pointed out that ‘the law is that I have two lawful witnesses and here is but one‘. He was told ‘Thine heresy is so heinous and abhorreth thine own brother so much that it forceth him to witness against thee, which is more than two other witnesses‘.

John Marbeck was accused of uttering sacrilegious words against the mass. He claimed they were not his own words but those of John Calvin, which he had simply copied out long before the Act of Six Articles was promulgated. However, as he could not prove when he had done it he lost the argument.

The jurymen went off to consider their verdict, and Simons took it upon himself to go and sit with them. Eventually, a man called Hide, from Abingdon, pronounced the accused guilty and they were told to prepare themselves to die next day.

Even then they were further tormented because on the Friday the news came that they would not die that day. The Bishop of Salisbury had decided that there was something to be said for believing Marbeck. He wrote to the Bishop of Winchester who went to the King and obtained a pardon for him. Why it was requested and granted is not known. Some said that the Bishop of Salisbury’s conscience pricked him, others that the Bishop of Winchester hoped that now he could break Marbeck’s will and get him to indict others of heresy, yet others that the king admired Marbeck’s musicianship. At any rate, the town rejoiced at Marbeck’s release.

Pierson, Filmer and Testwood were not so fortunate. There was no reprieve for them. Before their execution on the Saturday they were offered and accepted confession. Pierson’s confessor was a canon, Dr Blithe, with whom the irrepressible Anthony was arguing to the last. His parting shot was ‘Do you call him Dr Blithe? I call him Dr Blind!‘

The three took their leave of Marbeck, praising God for his deliverance and asking for his prayers. They were led through the streets asking people to pray for them and to stand fast in the truth of the gospel. It is clear that the crowds were deeply moved by their bearing and cheerfulness. The route took them past the house belonging to Filmer’s brother. He called and called buthis brother remained out of sight. ‘And will he not come?‘ said Henry, ‘then God forgive him and make him a good man‘.

On the low-lying wasteland below the castle and east of the hundred steps, the three men were tied to a stake, the brushwood was piled around them and they were burnt to death.

But what of Robert Bennett who was left in the Bishop of London’s jail suffering from the plague? Bennett was, strange to relate, a close friend of his fellow-lawyer, William Simons. Although they disagreed profoundly on religion it is recorded that ‘in all other worldly matters they cleaved together like burrs‘. Bennett’s wife went to see Simons in great distress and he agreed to obtain a letter from the Bishop of Salisbury asking the Bishop of Winchester to approach the King for a pardon for Bennett as he had done for Marbeck.

However the investigations before the trial had revealed that the priest Pierson had the support of friends at court. An attempt was made to name these men and their wives and to indict them of being ‘aiders, helpers and maintainers of Pierson’, and the request for Bennett’s pardon was forwarded together with these indictments to Gardiner. The papers were intercepted and brought to the King as examples of the unsubstantiated evidence by which the men had been convicted. The King quashed the charges against the members of his Privy Council who had been implicated, and granted a pardon to Bennett. Upon further enquiries into the trial he withdrew his favour from Gardiner although the Bishop survived to conduct other infamous heresy- hunts.

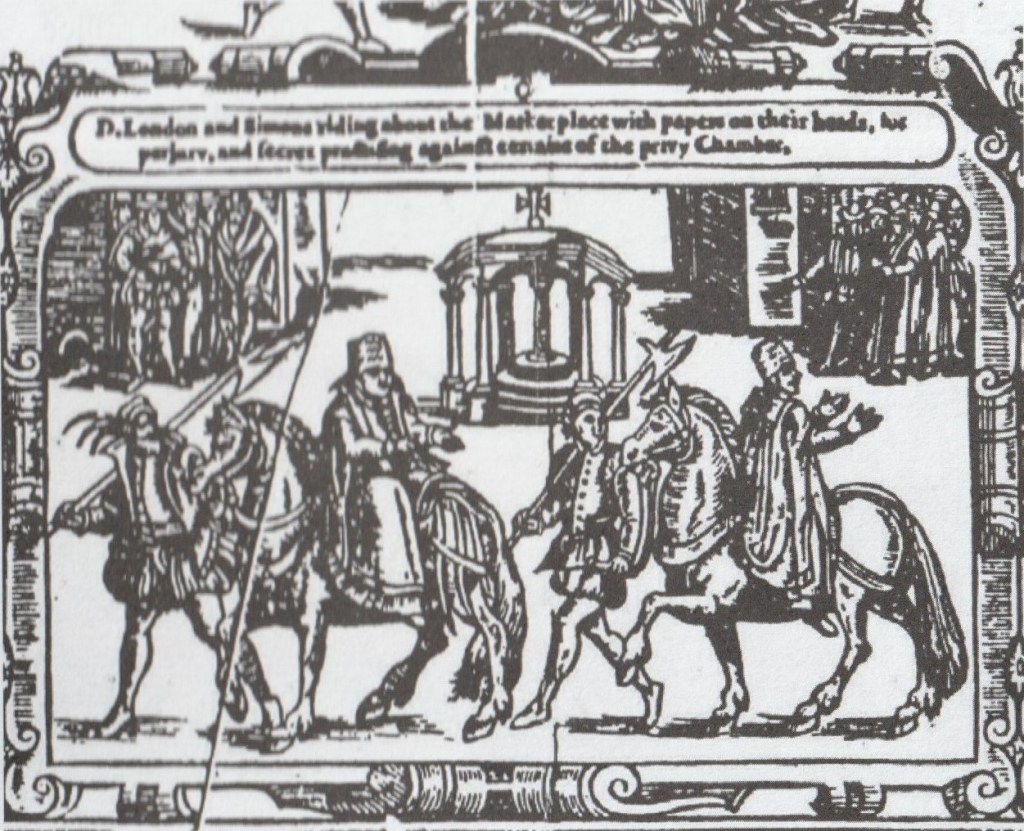

Dr London and William Simons were arrested, examined before the Council, and found guilty of perjury. Their punishment was the humiliation of being made to ride, each with his face to the horse’s tail, through Windsor, Reading and Newbury, and to stand in the pillory. They were then committed to the Fleet prison and Dr London died there soon afterwards.

Whatever may be our view now of the issues involved, there can be no doubt about the courage and steadfastness with which Pierson, Testwood and Filmer faced trial and death. Foxe’s book, which included a woodcut illustrating in graphic detail the Windsor martyrdom, soon became one of the most widely read books in England. The qualities displayed by the martyrs still command our respect and make the same deep impression upon us now as they did on the people of Windsor in 1543.

Jean Kirkwood

Note: This is a shortened version of the article that was published in Windlesora number 1 in 1982.