Published in Windlesora 27 (2011)

© WLHG

The Death of King Edward VII on 6 May 1910 brought the Duke of York and his wife, May of Teck firmly into the roles of King and Queen. With one year to plan for their coronation both were besieged by minor relatives and hosts of civil servants: ‘I am getting worn out and people bother one so … I am sick of the everlasting begging for favours …‘ the new Queen Mary wrote. When the coronation took place on 22 June 1911, the glorious spectacle unfolded under showery skies. King George V and Queen Mary returned to Windsor after the ceremonies in London, and His Majesty graciously knighted the Mayor in the High Street making him Sir Frederick Dyson.

The busy year continued with a State Visit to Ireland followed by the presentation of the Prince of Wales to the Principality of Wales in a colourful pageant at Carnarvon Castle. On the horizon however loomed the greatest coronation display of all, the Indian Durbar. To be staged in Delhi in December it would need immense planning if it was to impress the world.

However, trouble on the political front in Britain and abroad was never far away. Germany was engaged upon a dangerous naval arms race, suffragettes were becoming more raucous in their demands and a renewed bout of industrial unrest was threatened among coal miners and dockers. Many political insiders were aware that the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith was said to be drinking rather heavily and his daughter Cynthia was ‘… not alone in fearing it was the beginning of a French Revolution …‘

It was with this mounting crescendo of problems that a crippling strike of railwaymen took place. At Llanelli in Wales shots were fired when strikers tried to block the railway line as soldiers manned the trains to keep them running. At Windsor the Mayor tried to offer support to the loyal railwaymen who did not take industrial action but received practically no wages and were sent home. The rail companies were unable to run reliable timetables and carry on the normal business of carrying freight.

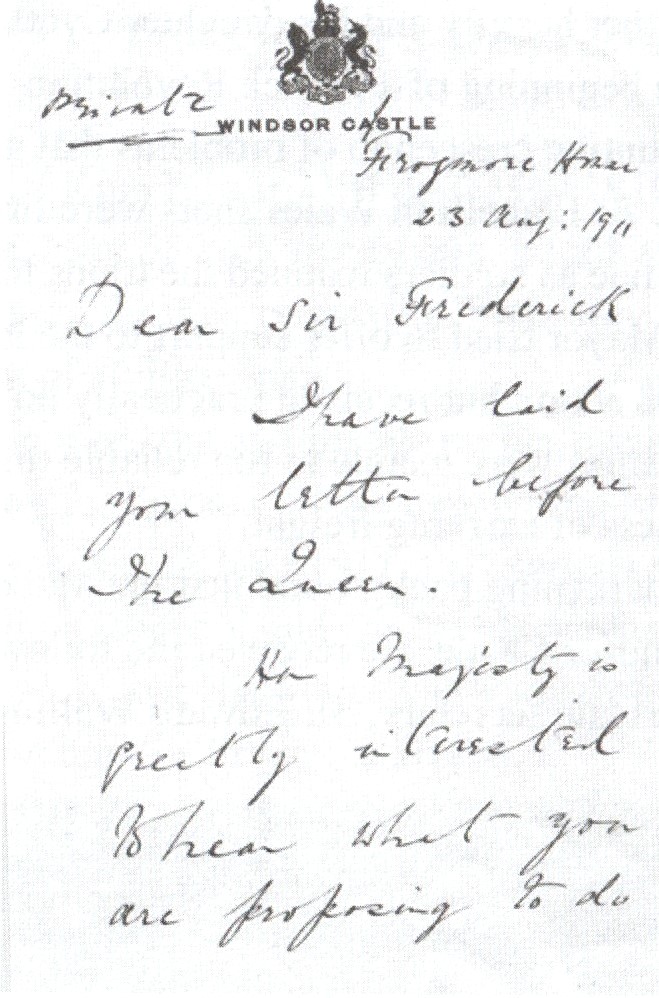

It was against this darkening background that the Mayor of Windsor wrote to the Queen at Windsor Castle. He received the following tactful letter from the Queen Mary’s private secretary, Sir Edward Wallington:

Private

Frogmore House 23 Aug; 1911Dear Sir Frederick

I have laid your letter before The Queen.

Her Majesty is greatly interested to hear what you are proposing to do for the local railway men who remained loyal to the Companies during the recent strike.

The Queen feels sure you will understand that it would not be possible for Her name to be mentioned in connection with the Fund, but by Her Majesty’s commands I am sending you five pounds, which the Queen hopes you will receive anonimously [sic] and add to the Fund to be collected.yours very truly

E.W.Wallington

The Queen was well served by Sir Edward in this matter and he continued to act in her interest for many years. He admired his royal mistress greatly and wrote this of her:

‘she was an example to the housewives of Britain for wise shopping, careful spending and discriminating choice. I have been on hundreds of shopping expeditions with her and I was always amazed by her grasp of current prices and the discrimination she showed in buying the right article. I never found a flaw in her bills. She is too good a housewife.’

The industrial unrest was eventually settled by the Chancellor, David Lloyd George, in August 1911, earning a note from Mr Asquith who was deeply grateful for his adroit intervention. The Indian Durbar was set for December 1911 and King George V and Queen Mary were able to concentrate on this great event with lighter hearts.

Chris Vivash

Sources

Clifford, Colin, The Asquiths John Murray, 2002

Pope-Hennessy, James, Queen Mary George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1959 The Times

Sir Edward Wallington’s letter is from an unpublished private collection.