– More Aerial History of Windsor

Published in Windlesora 03 (1984)

© WLHG

After George III’s experiments with a hydrogen balloon at Windsor Castle in November 1783 (Windelsora No. 2) the next news of ballooning came when Lunardi made his first ascent in London on September 15th 1784, witnessed by the King and his ministers who stopped a meeting to watch him depart. “Alas,” said George lll, “we may never see poor Lunardi again” . . . but Lunardi not only landed safely, first at North Mimms, where he unloaded his cat, “which felt the cold,” then he was up and away again, pursued by fifty horsemen, to Ware. The first rider to catch up with the aeronaut took him out to dinner. The ascent had been expected to include Lunardi’s friend and patron George Biggin, an Etonian, an amateur chemist and inventor – he invented the coffee percolator. However, Lunardi’s hydrogen generator was not working properly, so there was only enough gas to lift Lunardi and his cat, and but for the providential arrival of George II’s expert on hydrogen generation, Aime Argand, the Swiss scientist (who found at about midnight the ground crew were too drunk to manage the generator properly) there might have been no ascent whatsoever. Biggin was not deprived of his balloon flights with Lunardi; he later made an ascent with the ample Mrs. Sage, whose value as ballast was such that on this occasion it was Lunardi who was left behind.

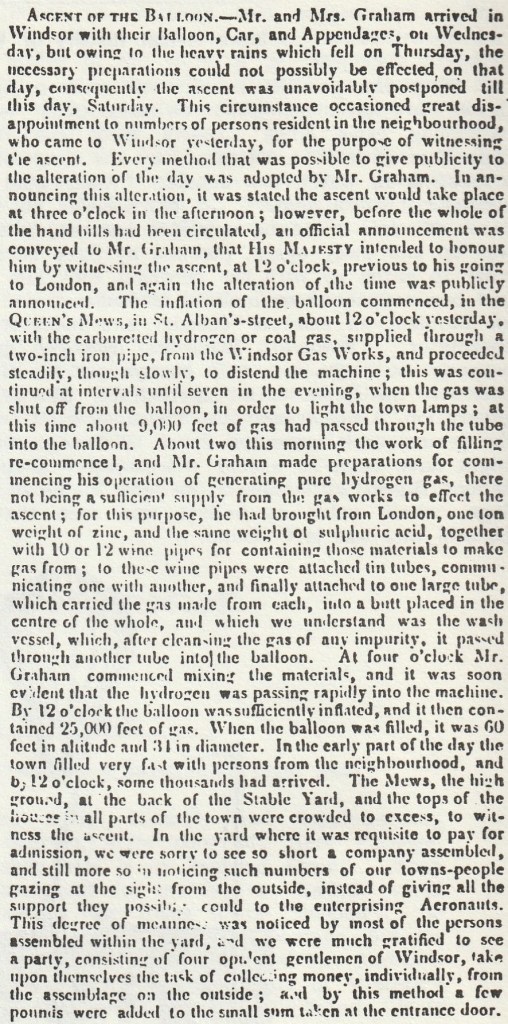

Nearly fifty years later, George Pridie, a Peascod Street cutler and engraver (1787 – 1858) who kept a brief record of local events in a notebook which bears the inscription “GEORGE PRIDIE – HIS BOOK” on the cover, wrote “on Saturday 3rd September 1831 Mr. Graham ascended in a handsome balloon from the Upper Mews,” (which were in St Albans Street). Mr. Graham augmented the town gas supply available in Windsor with hydrogen made on site. The Windsor Express dated 3rd September 1831 gave blow by blow details of the event, which heralded the Coronation of William IV.

The next edition of the Windsor & Eton Express reported that Mr. Graham had landed safely at Farely Heath in Surrey.

In London, the Coronation of William IV was celebrated by Mr. and Mrs. Graham making another ascent, this time from Green Park. They had written verses about their Windsor ascent and the Coronation, and threw 400 copies down from their car to the crowds below.

It was their 113th ascent, and the first made with town gas alone, rather than with hydrogen, or a mixture of hydrogen and town gas at Windsor the previous week.

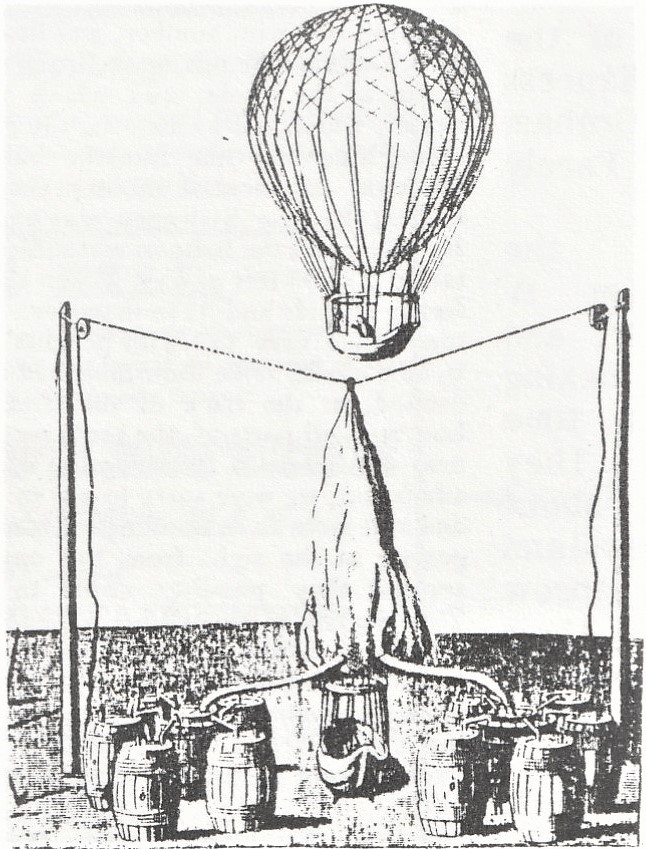

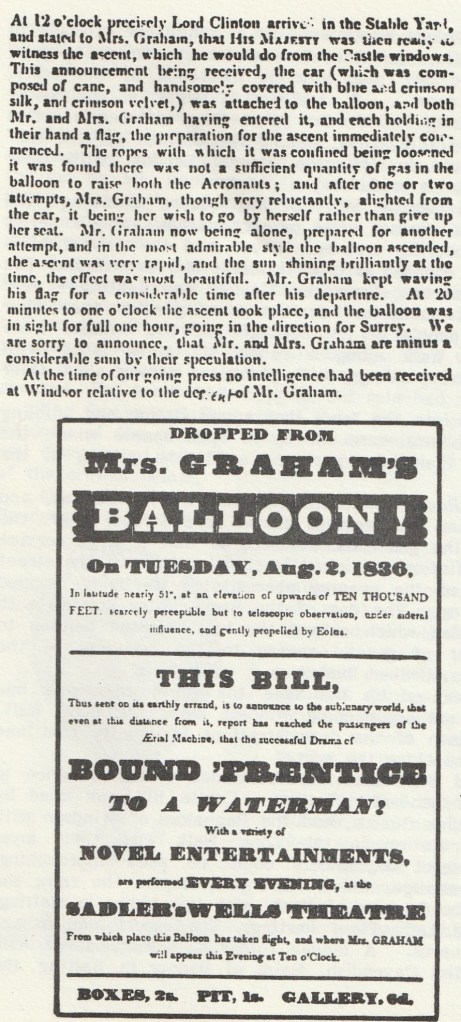

Dropping leaflets from their balloon was a favourite method of advertising used by the Grahams, as shown by the illustration above. Mr and Mrs Graham returned to Windsor with their balloon, the “Royal Victoria” for an ascent on 22nd August, 1837 as part of the celebrations in honour of the State Entry into Windsor of the young Queen Victoria after her Coronation.

About that time, Mrs. Graham wrote a letter in which her attitude to ballooning becomes clear; “The idea that 1 was daring enough to push myself as 1 may say, before my time, into the presence of the Deity, inclines me to a species of terror . . .” And well it might, as the couple rarely had an uneventful ascent. Over the years they suffered a series of mishaps, including on June 16th, 1851, pulling the cornice off the roof of the Prime Minister’s house in Arlington Street, London, with their grapnell, and then landing on his roof.

The Windsor Express related the story of the Queens’ entourage and slow journey from London to Windsor after her coronation, along a series of decorated streets and cheering crowds. Never had the arrival of a Sovereign at Windsor Castle created so much interest and excitement. The arrangements for triumphal arches, fireworks, flowers and lighting – over 3,000 lamps were used – banners and devices were greater than ever before. The poor and old people of the Borough and Old Windsor were given dinner in the Long Walk along a range of tables laden with substantial joints of meat and puddings, with plenty of strong ale. Over 4,000 were thus served.

So many visitors poured into the town that accommodation and stabling was impossible to find, and lines were set up in open spaces where the horses could be kept after their hard journeys, amid “the pelting of the pitiless storm.“

The Graham’s great balloon required 25,000 cubic feet of gas, and inflation had started at 7 a.m. the previous day in Park Street, where the road had been opened and the gas main exposed, so that a large service pipe could be provided. Inflation continued intermittently until the street and house lighting demand of the evening necessitated its being stopped until first thing next morning. The day of the State Entry started with heavy rain and gusts of wind which caused the half inflated balloon to roll tremendously, a matter of great concern to the members of the Committee. But Mr. and Mrs. Graham had seen it all before.

The weather had moderated by the time the royal cavalcade had reached the Double Gates and approaching Windsor along the Long Walk, later than expected by reason of the demonstrations of loyalty that had been encountered everywhere along the route.

The 2nd Lifeguards and their band were stationed at the entrance to the Castle, by the York & Lancaster Towers. Castle Hill was lined by the 1st Battalion of Grenadier Guards, and the Bachelors of Windsor with their band took up their station in the Long Walk with their loyal banners. At last the escort of lancers could be seen approaching, followed by the Queen’s carriage, which was open despite the rain; she was accompanied by HRH the Duchess of Kent, with two ladies in waiting, Lady Charlotte Copley and Lady Flora Hastings. The escort was formed by a squadron of Horse Guards. A landau followed containing the Hon. Miss Cocks and the Hon. Miss Cavendish, Maids of Honour in Waiting, the Baroness Lehzen, and Col. Buckley, Equerry in Waiting. All the bands played the National Anthem, while the most enthusiastic shouts and cheers rent the air. (The lamp lighters were busy, so that their task could be completed before darkness fell).

At six o’clock, when the crowds had gathered as near as they could to the great balloon, now more or less fully inflated, and with its car attached by Mr. Graham and his assistants, Mrs. Graham was handed into the car by Mr. Bedborough, a prominent member of the Committee. Park Street and its continuation to Old Windsor, Frogmore Road, the Long Walk and the surrounding area were so crowded as to be impassable even for equestrians.

A gentleman named Day from the Chester Wharf, Pimlico also stepped into the car, but as Mr. Graham started to release the mooring ropes, it became evident that the rain had added so much to the weight of the balloon that it would not rise until he had been persuaded to get out of the car, which he did very reluctantly. Then the balloon ascended slowly, with Mrs. Graham standing waving her handkerchief, while the crowds cheered. The winds had dropped, but rain had recommenced.

The Queen and Duchess of Kent had a perfect view from the Castle windows of the intrepid aeronauts as the balloon passed over Little Park and disappeared into the low clouds, followed by the continuous cheering of the crowds below.

Mrs. Graham was soon soaked, and brought the balloon down at Pennyoaks Farm, which is now the site of Heathrow Airport. (Thus, Mrs. Graham was the first aerial passenger to disembark there). Mr. Graham had chased the balloon in a carriage, and caught up with her at the King’s Arms, Longford, where the Landlord Mr. Godfrey provided facilities for her to change into dry clothing. They returned to Windsor in time to view the very splendid display of fireworks in the enclosure between the Frogmore Road and the Little Park, marred only by some rain-damped squibs. It had been Mrs. Graham’s 35th solo ascent, and the anniversary of her ascent with the mad Duke of Brunswick, which (the Windsor Express added mysteriously) “was likely to have terminated fatally to her . . .“

Despite their frequent accidents, both Mr. and Mrs. Graham died in their beds, and during their long married life Mrs. Graham presented her husband with eight children.

Gordon Cullingham