St Augustine’s Home, Clewer

Published in Windlesora 12 (1993)

© WLHG

A photograph of a petrol station may seem an odd illustration for an article about a home for destitute boys, but the house behind the forecourt of Maxwell’s garage in Clarence Road, Windsor was St Augustine’s Home for Boys and this is the only known photograph. The Home has long since closed, as indeed has Maxwell’s garage, and both have been replaced by new and far larger premises. Destitute boys have given way to fast cars, a sign of more affluent times.

St Augustine’s Home began on the initiative of one of the Sisters from the Community of St John Baptist, a Sisterhood of Anglican nuns based in Hatch Lane. Their work already included rescuing destitute women, orphan girls, and convalescent nursing. By the early 1880s their mission house in the parish of

Clewer St Stephen was thriving with a number of National schools as well as St Stephen’s College, a prestigious girl’s school. Several of the Sisters worked in St Stephen’s parish, one of whom was Sr Emma.

Emma Waring had joined the Clewer Sisterhood in 1869 and had become a professed Sister in February 1872. In January 1874 she, along with two others, had been sent to New York to begin a new foundation. She stayed there a year before returning to Clewer where she was sent to St Stephen’s. In a recently discovered manuscript in the Clewer Community archives Sr Emma gives an account of her work among the “scamps” as she called them, of St Stephen’s parish.

“On my return from working in the United States,” writes Sr Emma, “I was sent to St Stephen’s Clewer, my work lying a great deal amongst the Boys in and out of our National Schools; Amongst these there appeared so many ‘Scamps’ that I was quite baffled, especially as all my attempts to turn them into respectable members of society seemed to prove utterly futile. The difficulties seemed to lie with the evil surroundings and influences at home, that unless the scamps could be wholly transplanted the work of conversion appeared well nigh hopeless. How I longed to gather these choice spirits together into one house under a good master: then I felt quite sure, the good and clever side of their characters being cultivated, sensible means of occupation and amusement provided – the evil would soon drop off – and the Scamps reclaimed. But alas! this was an idea which appeared quite outside the bounds of possibility – was I not the poorest of poor Sisters, was not St Stephen’s altogether a poor work – our very neighbourhood proclaimed this from its housetops, and the very scamps cried out loudest in confirmation of the fact.”

It seemed as though the idea would progress no further until one day a boy called Jack Kells appeared on the scene. The Sister continued: “Now there was one boy, ‘Jack’ who came under our notice very often, and never for good – the eldest of three urchins whose mother dwelt in an upper room in a very low public house in Back Alley [called] the ‘Napoleon’. She went out to work at 8.a.m. and reappeared when she would, and that was a moveable festival for the three children… the day’s money having been spent in drink… Jack’s mother humoured him and Bob and little Amy… so that the three grew in independence, insolence and in the dishonesty which comes from such training without check.” Occasionally however, Jack would overstep himself upon which his mother would “Call him ‘All but Everythink’ and turn him out of doors for a night.”

The Sister’s concern was quickened by the following encounter between herself and the children. “One pouring day he and Bob and Amy sat in a row on the edge of the pavement eating some crusts soaked in the rain. ‘Jack, can’t you take Amy indoors, she’s wet through?’ ‘Mother aint at home, she’s got the key in her pocket.” The three went into peals of laughter at [my] concern on their behalf… But Tom Neil (a lad of sixteen) heard the laugh and came forward and challenged Jack to go into Rayner’s shop and take half a crown out of the till. Jack never hesitated, and as Rayner was busy and his wife not quite sober, he at last got the half crown and came away. It was at once spent in sweets and eaten. Then came Jack’s mother in tears — quite sober, quite tidy and oh so clean and civil. ‘Ah, Sister, if only you would get off my poor child this once! He’s up before the Magistrates and it’ll go hard with him they tell me. And so [we] were a little touched with pity for poor Jack for [we] knew how little chance he had of learning what was good. Jack was begged for before the Magistrates and let off with a thrashing.”

It seems as if the thrashing instilled some sense into Jack. He began to attend school, and even Sunday school. Alas it was shortlived for, as Sr Emma recounts, “when the summer Treat was over Jack went back again to the old ways, and Tom

Neil was always appearing furtively round unexpected corners to lure him… Then came another fall — and with it another visit from his mother. Would we get him off again… they said he would be transported at least, or she would have to pay a heavy fine, and what could she do! He had this time stolen seven shillings, all now spent in sweets. Tom Neil had had six shillings worth and Jack the rest. It was a second offence, her boy was ruined. [We] thought very seriously over all this -[we] could not think it right to beg Jack off – [we] knew that the only kindness [we] could do would be to ask the Magistrates to send him to a Reformatory, but Jack was under age… The Magistrates decided on another thrashing for Jack, and [we] stipulated that he should be brought straight to [us] immediately afterwards.”

So Jack was given another thrashing, a normal punishment at the time; but obviously Sr Emma was unhappy about it and saw in Jack not a potential criminal but a poor little boy whom no one loved. Her narrative continued: “Poor little Jack, what is to become of you! Behold then, Jack, his ragged coat sleeve covering a red and swollen face, his hair a perfect mop on top of it; his toes peeping out at the ends of what once were boots; torn trousers, torn jacket, torn rags of shirt… standing within the great doors of St Stephen’s College held by the arm by a very tall and strong policeman,… beside him his mother in tears.” But the mother’s tears did not appear to have been shed for the boy, for it seems she was only too keen to be rid of him. Much to the bewilderment of Sr Emma and her colleagues the mother said, “Here he is Sister — take him. I don’t want to have him back again. I don’t care what you do with him.” The policeman withdrew and the mother also, and Jack remained still standing heaving like the sea, his ragged coat sleeve still covering his red and swollen face, and so he stood for a long time.”

The Sisters were now faced with a major problem for they had no facilities for looking after wayward boys and yet the emergency had to be faced. In the event the lad was boarded out with a married couple, a Mr and Mrs Webb, who lived in Victoria Cottages in Windsor. Sr Emma feared he might run away before the morning, but he stayed and after a week or two began to improve in his behaviour. The Sister had undertaken to pay four shillings a week for his upkeep and, knowing that his mother would not provide it, set about begging the money from other people. The variety of excuses which they offered was very disheartening – the boy had lost his good character; others would not encourage a child who had behaved so badly to his mother (despite his mother’s own bad example); another only helped “good” boys; someone else had just given to Dr Barnado; others said “send him to sea”. In the meantime Sr Emma grew fonder of Jack and warmed to the prospect of reclaiming others like him. “Jack was behaving so well,” she recalled, “he was so changed and had begun to grow and to look clean and rosy and healthful, [that] we should not have had the heart to part with him… [But] ah, that call for ‘a good character’! I believe it was that which ripened up our plan of opening the Home, the ‘Scamp’s House’ as we usually called it amongst ourselves.”

Begging expeditions were a common source of income for the work of the Clewer Sisterhood at this time. So it was that Sr Emma found herself begging at the door of a lady in Winchester on behalf of St Stephen’s mission house. As a result of their conversation about wayward boys the lady later sent £50 to help found a Home. More money came in so that when the sum had doubled it was felt expedient to begin. “But,” wrote Sr Emma, “a great and unforseen difficulty now arose. The vicar of our parish, a most excellent man, and a dear friend among us, had a principle of objection to our plan. He thought it would be the introduction of evil into our parish, rather than the uprooting of evil in the individual cases.” The vicar of Clewer St Stephen, the Revd George Davenport Nicholas, had never been reconciled to the presence of the Sisters, who had actually founded the mission five years before his own arrival in the parish. This was simply another attempt to thwart the Sisters’ work. But not to be outdone they took the work outside the parish, as Sr Emma quaintly tells us. “We therefore withdrew from our own parish and opened our Home in Grove Road, Windsor, at least 20 minutes walk from St Stephen’s. This added much to the difficulty of the work, but anything would be better we felt, than to annoy our good friend, or to sanction an act of dishonesty.”

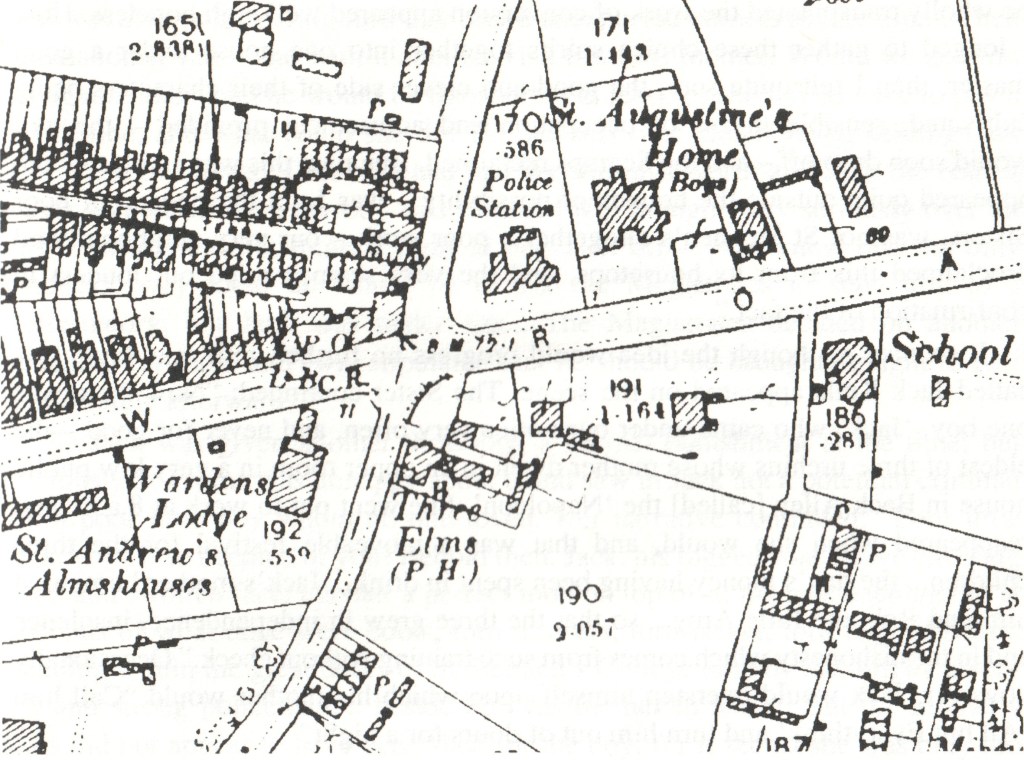

Mr and Mrs Webb were appointed Master and Matron with a salary of twelve shillings per week, and the Home was named St Augustine’s, a name which alas prompted some to call the lads the “disgusting boys.” Survival in those early days was very much hand to mouth, very few people seeing any value in helping wayward boys. It was not for want of trying: “The Mayor and Corporation were invited to participate in the scheme, and to contribute and have a voice in its management, but no one took it up,” wrote Sr Emma. “[We] were left to found and carry on the work in [our] own way — and [we] were very glad of this.” The house in Grove Road was soon outgrown and another sought, but prejudice about boys work was paramount. “No one would have us! All refused to let to a “Boys Home’”. The only place which was offered turned out to be haunted; the Sisters turned it down. “We thought children’s nerves could never stand a haunted house”, wrote Sr Emma, and then continuing more honestly, “and we were not quite sure about our own!!” Eventually three small cottages in Bexley Terrace, Clewer were taken and adapted, and this served for three years until 1887 when a purpose built house in Clarence Road was provided by the generosity of a Miss Wren-Hoskyns of Broadstairs.

Many of the early boys at the Home came from similar backgrounds to Jack Kells, and had literally been picked up off the streets. In time however, the boys tended to come from less neglected backgrounds. A number of places in the Home were regarded as free in order to accommodate cases of real hardship, but generally there was an entrance fee of £2 plus the 4 shillings weekly upkeep. It was common for a clergyman or wealthy lady to guarantee the boy’s fees, and sometimes to provide employment when he left. But when this sponsorship was not forthcoming it could mean real hardship for the boy’s family. Most of the boys were not orphans: St Augustine’s was not primarily an orphanage, but a home for the under-privileged. Some boys were orphans but a larger number were children whose parents for various reasons could not cope. There were cases of widowers left with several children whom they were unable to care for as well as working long hours; similarly, there were cases of women whose drunken and violent husbands had abandoned them with several children, or widows in poverty. Parental illness or disability was also viewed sympathetically. Some boys were sponsored by the Prisoner’s Aid Society which cared for the families of convicts; others were sent by the Magistrates as an alternative to prison or a reformatory. There were also boys who were difficult at home and, in keeping with contemporary thought, needed the discipline of an institution and the training in a trade which this would open up.

Some boys were unable or unwilling to live under the discipline of the Master and Mistress who lived on the premises and they either went back to their families or were sent to other Homes. Sr Emma, based as she was at St Stephen’s mission house did not live at the Home, but she kept a firm grip on the place, visiting daily, and little passed her notice. So when several boys ran away her suspicions were aroused. “Now although boys will run away, and although boys had run away before, yet it is always a sign of discontent,” she wrote wisely. “And if there is discontent there may be some cause, and when the offence became common I was very much disturbed … so I watched. Willie C. ran away, Cecil and Jesse were always running away, Harry Jones ran away, Willie Harrison ran away, and even Harry Wilson.” She did not have to watch for long. Willie C. was traced and brought back to the Home, “but” recalled the Sister, “he was in such an abject state of terror with regard to the probable thrashing which he thought might await him that I began to suspect the thrashing could not be administered with a very merciful hand. The boy’s terror was so great as to threaten serious nervous consequences, and I at once forbid the Master to touch him – I thought the a

gony of mind he was going through was sufficient punishment.” However, it seems that the Master was a devious man who thought he could outwit Sr Emma. She continued: “The Master differed from me in opinion, [and] he was very much put out, so much so indeed that he invented a punishment far more degrading to the child’s self respect, and carried it out without my knowledge.” This was the last straw and when Sr Emma found out she dismissed him. “Who will blame me for feeling that in such a case the Master was no longer fit for his position – he therefore received notice to quit and after due time given him to seek other employment was dismissed. I have never regretted losing him for as is so often the case, I found that his vindictive spirit had in many cases led to concealment from me of the real state of discipline with the boys, and a change had become necessary.”

The question of corporal punishment is of course an emotive one, and a hundred years after these events the attitude of society is wholly different. What was then regarded as punishment is now seen as physical abuse. It is quite clear that Sr Emma found the whole process distasteful whilst reluctantly conceding the necessity for discipline. But the Master had exceeded his brief and there was no question of his continuing in office once his sadistic nature was revealed. The new Master and Matron, a Mr and Mrs Wilkes, had been known by the Sisters for some time and their appointment was made on the understanding that “the Sister’s word was law, [as] binding as that of the Medes and Persians.”

As to the runaway boys, Sr Emma recounted their cases with some affection and not a little amusement. “Harry Wilson came back very penitent; he had been out all night in a bad thunderstorm and was too thankful to cry and beg to be forgiven and be allowed to dry himself by the great kitchen fire at the College. Willie Harrisons experience must have been still more terrible for he could never speak of his escapade without floods of tears, and 1 forbid further enquiry to be made, as he evidently had no intention of repeating it.” But not all the runaways were able to stay: some were difficult, disruptive boys, and there came a point when they had to leave for the sake of the others. Thus Cecil and Jesse “had to be sent away in sad disgrace.” Willie C. whose return heralded the Master’s dismissal, was later dismissed himself for bad conduct. But dismissal did not always mean the boy was destined to lead a bad life: “Harry Jones was dismissed after his third expedition, and we feared his sojourn of eight months in the Home had been quite thrown away — but no, a letter from the kind lady who sent him told me he was an altered boy, no bad words, no violent conduct.”

The final section of Sr Emma’s account tells of what became of some of the boys. “Charlie Checklie was sent to a farm in Yorkshire where he went with great joy and was thoroughly satisfactory both in character and desire for work… Stephen Port was sent as a doctor’s boy in Herefordshire… and is very happy in his work… Jack Kells our first boy is a great fellow now of 16 – a regular Communicant, and appointed a Monitor in the House; he has become quite honest, which for a long time he was not, and as he wishes to stay, we keep him to train up into a sort of sub-master… Willie Young is also a Communicant – he is working with [a] plumber and glazier in Windsor with wages now advanced to 3/6 a week, exclusive of pocket money… Harry Wilson is learning his trade as Carpenter and Builder with Mr Green at Clewer [and] he earns 6/- per week… Willie Harrison and Albert Hurst are both in printing offices earning 2/6 per week each.” Some boys were forcibly removed by relatives: such was the case of Albert Roper who was doing well at a plumber’s trade when “an uncle, a sugar boiler in the East End, heard of his success and wanting a boy, descended upon me as an eagle on the prey, and with a crooked story and most unjustifiable deception, decoyed the boy away with him to the sugar boiling. We have heard nothing of him since.” Sr Emma was ill for a time during which a boy was dismissed without her knowledge: “William Ellis was sent away in disgrace at a time when I was too ill to be consulted. I was much distressed at his going when I knew of it.” With characteristic humour she went on to explain: “he was a gypsy boy who could turn a [cartwheel beautifully – and could stand on his head, on a gallipot, and naturally I was proud of him.” A number went out to domestic service; others became gardener’s boys; one or two took apprenticeships as boot makers; a number became errand boys for local shop keepers. Several boys went to Yorkshire to the coal mines, indeed two died in a pit disaster. Another common employment was to join a training ship, and others joined the Army.

The Clewer Sisterhood believed in using the talents of individual Sisters. St Augustine’s Home was never a separate branch house of the Community, but remained very much Sr Emma’s brainchild in conjunction with her work at Clewer St Stephen. She was fortunate in having the support from the outset of Sr Emily, the indomitable Sister-in-charge of St Stephen’s mission house. Because the Home had no official branch status Sr Emma took sole responsibility for the financial arrangements: “I am, I fear a terrible beggar, there is no doubt of that” she wrote. She was also a very effective one, even succeeding in extorting £30 from her brother who many years previously had objected to her joining a Religious Sisterhood.

She died on March 22nd 1909 and was buried at Clewer on March 26th. Doubtless she would have been glad to know that a number of her old boys came to the funeral. Inevitably, her death marked the end of an era for St Augustine’s, also new standards began to be applied to institutions, and new building regulations. The work struggled on until 1921 when it closed: a casualty of the post-War world. There is one element which runs through Sr Emma’s account of the Home: it is her love for her boys, and the special rapport which she had with them. The outbreak of War in 1914 saw many of her boys, now grown up, respond to the call for King and Country. Many did not return: at least she was spared that sadness.

Valerie Bonham

Acknowledgements

The Revd Mother Superior CSJB, for access to material in the Clewer Community archives.

Mrs Beryl Hedges for permission to reproduce the photograph of Maxwell’s garage.

Sources

Clewer archives: two manuscript accounts by Sr Emma CSJB, A Short History of St Augustine’s Home written at the request of a kind friend, and Some Further Account of “St Augustine’s Home” “Clewer, Windsor.

BONHAM, Valerie A Joyous Service: the Clewer Sisters and their work 1989 ISBN 0 9508710 1 X