The Early Years of Clewer St Stephen

Published in Windlesora 11 (1992)

© WLHG

As one approaches Windsor along the relief road, two churches come into view: to the right near the river there is the ancient parish church of Clewer dedicated to St Andrew, and to the left, rising up from amongst the surrounding houses the much larger Clewer St Stephen. The area served by Clewer St Stephen is much different in character nowadays from that of the 1860s when the first mission was established by the Community of St John Baptist in the slum district known as Clewer Fields or the Gravel Pits.

The development of the mission and its subsequent growth into a thriving parish church surrounded by several schools was due to three people — the Revd T.T.Carter, rector of Clewer and co-founder of the Community of St John Baptist, Clewer; Sister Emily CSJB; and the Revd George Davenport Nicholas, curate of Clewer and subsequently first vicar of St Stephen’s.

Carter had been rector of Clewer since 1844; it was a sprawling parish covering a large area of the town with densely populated courtyards and alleys which were abodes of vice and over-crowding, and by contrast, rural hamlets west of the town containing both poor cottages and country mansions. One of Carter’s earliest concerns had been to rescue women and young girls whose lives were being ruined in the brothels, beer houses and lodging houses which abounded in the garrison town of Windsor especially in the Clewer Fields area. This work of moral rescue formed the initial work of the Community of St John Baptist whose large convent began to rise above the Clewer skyline during the 1850s. Thus it was that once the Community had become more established, and the Sisters had increased in numbers sufficiently to expand their work, one of the priorities should be the slum district of Clewer Fields.

Harriet Monsell, the foundress and first Mother Superior of the Clewer Sisters had an extraordinary gift for recognising and utilising the talents of others. Thus when a young woman called Emily Hutchinson requested admission to the Community despite the misgivings of her father, an Evangelical clergyman who disapproved of all “Popish” things, (which in his mind included Sisterhoods), Mother Harriet recognised the determination of this young woman to follow her calling. It was to accommodate such as Emily that a Second Order had been founded at Clewer: members lived part of the year at home and part at Clewer, and made their commitment for three years at a time and followed a simple Rule. Emily’s father reluctantly accepted her admission to the Second Order and following his death she was admitted to the First Order as a novice in February 1863 and was professed on November 30th 1864 aged 29 years. While Emily was still a novice Carter asked Mother Harriet for a Sister to help establish a mission house in Clewer Fields. Despite her youth and junior status Emily was chosen; in her wisdom Mother Harriet had recognised in Sister Emily the qualities which the task required, namely, strength of character and a determined spirit. She was not mistaken in her judgement, and the young novice was to make Clewer St Stephen as it became, her life’s work.

Carter had secured the use of a room in a cottage and it was here in 1863 that Sr Emily began her solitary work. Once a week either Carter or his curate, had held an evening service but with little success, and so the Sister decided to start a ragged school hoping to establish some rapport with the children in the hope that their parents might also be drawn in. An early account describes the Sister’s method: “A stove in the middle of the room was the only furniture. Into this room the Sister gathered the children she had picked up. They sat round her on the floor —a flock of ragged, bare-footed, unwashed children. Her first proceeding had been to entice one child in to be washed, while another watched at the door, who, seeing the result was apparently satisfactory, consented to be washed also, and so on till seven had some of the grime taken off.” That the washing was necessary leaves little room for doubt; what is more remarkable is that Sr Emily did the necessary ablutions herself. As the daughter of a clergyman she would have come from a home where servants would have performed all menial tasks. She would certainly not have been accustomed to manual work but seemed quite prepared to do so for these poor and incredibly dirty children of the streets.

The home life, or lack of it, became apparent when she questioned her young charges, and she could not have been prepared for the horror of some of their answers:

“Have you ever heard of God?’ All shook their heads. At last one exclaimed, ‘I knows. You mean the Devil.’ Nothing more intelligent was at first evolved.

“Who are your parents?”

’‘Don’t know, never had none.””Where do you live?’

’‘Anywhere.””Where do you sleep in the night?’’

’‘Anywheres. Outside in a cart.”Always in a cart?”

“Yes, its warm in the straw.’’“Where do you get your dinner?’

‘Dinner? What’s that?’

‘Food. Victuals.’‘Ah yes, what we picks up, or e’er one gives us a bit here and there.’ ”

The narrative goes on to recount that:

“it was difficult to tell which were girls and which were boys. One garment was considered enough, and that seemed shaped according to one pattern. Boys and girls were equally ragged, equally shock headed, equally barefooted and used equally bad language.”

The young Sister must have been tempted to give up in those early days, so discouraging must it have seemed. While her primary object had been to give them religious instruction, we are told that besides this, she had to “teach them cleanliness and civilisation.” Nevertheless, she carried on regardless and soon reached the stage when she felt it would be appropriate to take them to Clewer church for the Sunday service. Of course, no one had anything decent to wear in an age when Sunday worship demanded Sunday clothes and so she begged old clothes from neighbours and painstakingly altered them to fit the children. Good Friday came, and Sr Emily fixed some pictures of Christ’s passion around the walls of the schoolroom. Then carefully leaving the door open, she led the children round the room in a home-made version of the Way of the Cross. Upon hearing singing the adults became curious and looked in, whereupon they were invited to join the small procession.

Carter had been observing Sr Emily’s progress and by 1866 deemed the time right to consolidate her efforts. There had been a limited amount of slum clearance, though it was not until the 1920s that the last vestiges were removed. But a very gradual improvement began in the area from the mid-1860s with the building of new artisans’ dwellings such as Bexley Street. In turn the children attending the ragged school became less rough and there was a general improvement. A room was taken for the school in Bexley Street, and then two Associates of the Clewer Sisters gave money for purchasing a site for a mission house with enough space to build a permanent church later. This stroke of good fortune put the work on an entirely different footing and the prospect of developing not only schools but also a new church opened itself up.

Work on the mission house began at once and the foundation stone was laid by Carter on Wednesday July 3rd 1867. A procession was formed by the school children, Sisters and clergy who went from the old school to the site of the new building where the service was performed. Possession was taken of the new building on April 23rd 1868 and a week later the new schoolroom was solemnly opened with prayers led by the Revd G. D. Nicholas who had been appointed priest-in-charge of the mission.

George Davenport Nicholas had arrived in Windsor in 1860 soon after his ordination as deacon, and he served as curate of Holy Trinity until 1862 when he left to become Vice-Principal of St John’s Theological College in Newfoundland. This appointment was short-lived and in 1864 he returned to Windsor as curate of Clewer, an appointment which was superseded by his becoming priest-in-charge, and subsequently vicar, of Clewer St Stephen. Nicholas was a complex person, not an easy man to get on with, as all who had to work closely with him were to find. His private journal, which he kept from the day he came to St Stephen’s until the day he left in 1917 not only provides a graphic description of the early years of a Victorian parish church but also gives much insight into the life of a lonely, hyper-sensitive and frequently embattled priest.

The ragged school begun by Sr Emily was by now far from ragged and all sorts of children begun to be catered for. Nicholas’ journal mentions a school for “the middle classes” which was opened in July 1868 with a charge of 6d a week for children under 8 years and 1/- for older children. Just a few days later he notes that “the Industrial Girls began sleeping in the Mission House which was from this time regularly inhabited.” These so-called industrial girls were the older girls who were being trained in laundry work and housework as a preliminary to domestic service. At the same time a number of requests were being received from clergy and professional men for the Sisters to educate their daughters, and from 1868 the school developed along these lines. From 1872-7 the parochial National schools were built nearby, and it became possible to separate the fee-paying pupils in what now became St Stephen’s College from the parish schools.

On Thursday, October 29th 1868, St Stephen’s Mission was formally dedicated. The upper schoolroom had been made into a chapel until a separate church could be erected, and an early photograph shows an altar standing on three steps adorned with brass cross, candles and vases of flowers, with an embroidered frontal overlaid with lace. A screen separated the sanctuary from the rest of the room, and two embroidered banners stood at either end of it. The dedication service was impressive and was carried out with much high church ceremonial. At 8.45. a.m. Carter blessed all the sacred furnishings i.e. chalice, paten, candlesticks, vestments and linen. Then six boys from Bell Farm school in the parish, clad in cassocks and surplices led the procession as it made its way throughout the building, before returning to the chapel. At the Holy Communion service which followed, linen vestments were worn, Carter being the celebrant with Nicholas acting as deacon and another curate (R. J. Ives) as sub-deacon. About 40 people received Holy Communion “‘poor as well as rich” so Nicholas tells us. In the afternoon the poor of the district were given tea and cake, and by all accounts it was quite a party with about 200 children, 40 regular attenders of the Mothers’ Meeting and 18 girls from the Friendly Society.

Thus the mission house began with a flourish and a regular pattern of Sunday and weekday services was established with a number of clubs and guilds catering for all. There was a religious framework to all these activities but there was also a valuable social element; boys and men were presented with an alternative to the street corner or the beer house; women and girls were given help in learning how to improve themselves and their homes; mothers were given assistance in saving their pence for buying food at Christmas or boots for the children; children were given an annual outing or a present from the Christmas tree — a treat indeed.

It was not long before the chapel in the upper room was so over-crowded that the distant prospect of a church became an urgent necessity. A friend gave £1,000 anonymously to enable the work to begin and on the strength of this donation thedecision to proceed was made. The ground was marked out in September and on November 9th 1870 the foundation stone was laid with much ceremonial on what we are told was a very foggy day. Next day the workmen were given a supper at which they enjoyed meat, puddings and cheese, followed by pipes of tobacco.

Carter collapsed with a chill in January 1871 and became so seriously ill that he was sent away from the parish to recuperate. In fact he was absent for two years and had to follow the progress of the new church by post. In the meantime Nicholas aided by the other curates (whom Carter called the “venerable Synod”’) ran the parish as well as the mission house together with all the preparations for the completion of the new church. It was an exciting time for all and one can sense Carter’s growing frustration at being so far away from the centre of activity.

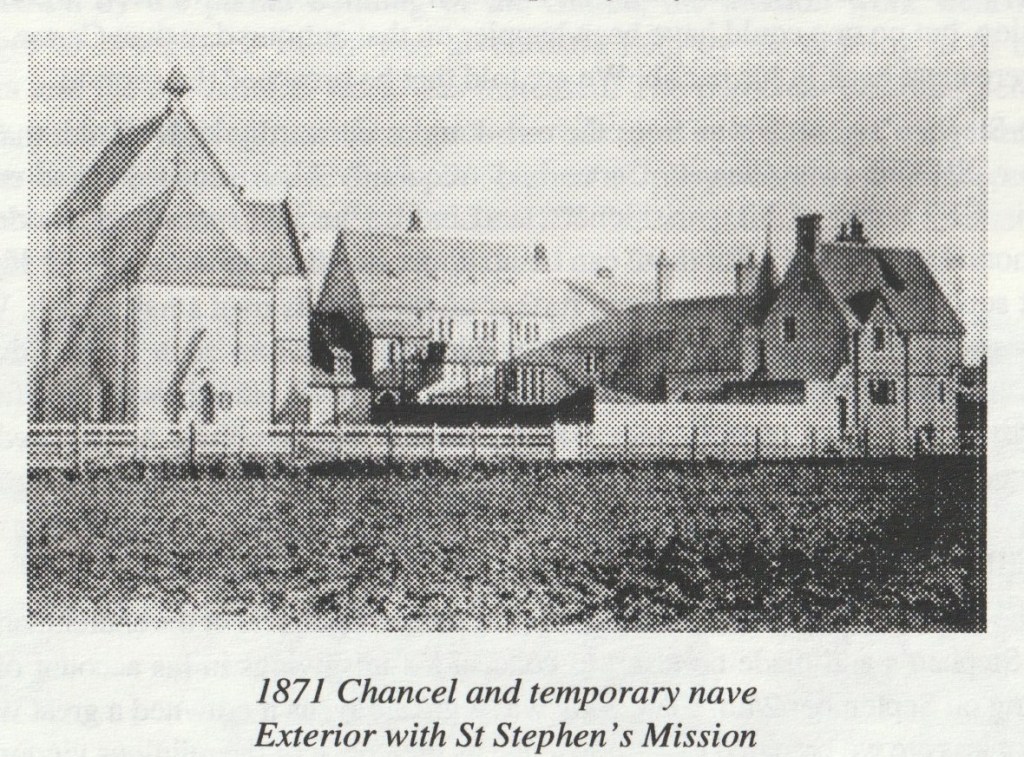

On July 25th 1871 the new church was opened — or at least part of it. Like the donors of the great medieval cathedrals the Victorians built their churches piecemeal. When the money ran out they stopped, raised more funds and then started again. Thus the church of Clewer St Stephen originally consisted of the chancel and part of the nave. A photograph taken in 1871 shows the truncated church together with the mission house next to it. A second photograph shows the interior furnished in similar manner to the mission house chapel, with Nicholas sitting in his stall and two Clewer Sisters, one of whom must have been Sr Emily, sitting opposite. Poor Carter must have felt abject at missing this grand occasion but was recompensed with these photographs: “I am delighted with the photograph of St Stephen’s and yourself in it. How well it looks. And so my long story comes to an end…” Not quite though — he was to live another 30 years.

The architect of St Stephen’s was Henry Woodyer, friend of Carter and no stranger to Clewer. As well as carrying out a full scale restoration of Clewer parish church which he did tastefully and sympathetically, he was also architect of the vast range of buildings within the parish which formed the mother house of the Community of St John Baptist.

There is nothing like a promising start to give an incentive for work, and spurred on by the partial building of the church, the mission work went from strength to strength. Sr Emily was given extra help by the drafting in of other Sisters and the educational work was increased. The parochial National Schools which were developing near the church were helped by the Sisters who went on regular begging trips to raise funds. St Stephen’s College continued to increase in

numbers and educational standards and in 1873 the mission house was extended to provide further accommodation.

On May 11th 1873 Nicholas noted in his journal that a Te Deum was sung after Evensong in thanksgiving for the gift of £3,000 for the building fund. Further generous gifts followed and on July 7th the contract for the building of the nave and aisles was signed by Nicholas and the builders, Wheeler Brothers of Reading. A few weeks previously, on June 10th, Nicholas had been instituted to the Perpetual Curacy (Titular Vicarage) of Clewer St Stephen by the Bishop of Oxford in his chapel at Cuddesdon.

The completed church was ready for use though not quite paid for by September 1874. The opening ceremony took place on September 24th but the church was not consecrated until December 22nd by which time the debt was paid off. The church was opened amidst the usual high ceremonial, and it must have been a glorious occasion, but no one could have been happier on that autumn day than Carter, now recovered and back in his parish. We are told that he preached the sermon.

St Stephen’s church was from the outset more outwardly high church than its mother, St Andrew’s Clewer. Carter had frequently been accused of so-called ritualism by some of his parishioners, and indeed he had introduced moderate ceremonial at Clewer. But there can be no doubt that St Stephen’s was far higher and it soon attracted followers from further afield than its own small parish. With the passage of time there were some wealthy benefactors such Lord Edward Spencer-Churchill who lived at Queensmead in Windsor, but this lay in the future and during the early years finance was a problem. Not everyone appreciated the high church trend within the Church of England; a small vocal minority saw it as Popery thinly disguised, something which a more ecumenically minded age may find difficult to understand.

The editor of the Windsor and Eton Express was very critical of the churchmanship of St Stephen’s and made no effort to conceal his misgivings in his account of the opening on September 24th:

“Thursday was a great day, as it crowned a great work; and not less are we prepared to acknowledge its greatness, or the religious vigour and life which has brought it to a successful issue, because we regard with pain and sorrow that principles and practices so nearly allied to Romanism should be openly taught and observed in a building connected with the Established Church of the land… The Church is now opened… and the parishioners, for good or evil, are under the regime of Ritualism… We may draw attention to the fact that all the leading characteristics of the Ritualists prevail — that in the celebration of the Communion the ‘real presence’ is insisted on, and is accompanied by an elaborate ceremonial characteristic of the Romish mass; lights burn upon the altar; and an excessive reverence is paid to the elements. The usual sacrificial vestments are worn… [and] we find from other sources that what is called ‘Sacramental Confession’ is enjoined… It cannot be asserted that such practices and doctrines are in character with the Protestant character of the Church of England.”

Windsor & Eton Express of 24th September 1873

Despite this somewhat hysterical outburst from the otherwise fairly staid columns of the Windsor and Eton Express very few people took any notice. St Stephen’s was built in a poor district to serve the poor, although its congregation was in time augmented by the young ladies from the College and a wealthy eclectic element. It was when high church practices were introduced into well established parish churches such as Clewer that the more Protestant-minded parishioners began to complain. Thus when Carter was persecuted for alleged ritualism at Clewer throughout the 1870s, the protests came from wealthy parishioners who counted themselves members of the parish church irrespective of how frequently they attended.

The consecration of the church by Bishop Mackarness of Oxford on December 22nd 1874 came as the crowning glory in a great work. But there was much more to be done both in terms of mission work and in completing the building. The bare interior needed adornment with mosaic, fresco and stained glass and this was done over a number of years. Space does not permit a detailed description but mention must be made of some features, notably: the reredos behind the high altar designed by Woodyer and erected in 1876 depicting the vision of St Stephen; the west window depicting the six deacons appointed with Stephen; the pre-Raphaelite style wall paintings which were the work of G. W. Ostrehan whose brother was curate at the church; and stained glass windows by Hardman of Birmingham.

Not only did the church flourish but also the schools were in great demand. The College catered mainly for boarders and in time there was a demand for something similar on a daily basis, and so from 1877 the work was divided into two branches. But it was not until 1882 that Sr Emily appointed a secular Head Mistress (Miss Du Pre) after which St Stephen’s High School, as this new foundation was called, flourished. In time the High School also took in boarders and there was tremendous rivalry between them and the College. Both schools catered for girls from similar backgrounds although the High School had many more local girls on its roll. Sr Miriam was associated with the High School for many years and was a guiding force.

One would have thought that Nicholas would have given his unreserved support to the Sisters’ educational work, bringing as it did a steady supply of Confirmation candidates, and boosting the congregation in term time. In fact there was bitter resentment on his part towards this work as it developed over the years. Nicholas could never come to terms with fact that Sr Emily had worked in the parish longer than he had, and that she had begun the original mission work. One suspects it was something which she liked to remind him about! It would certainly not have gone down well with his misogynist frame of mind. Sisters were not the only ones to fall foul of Nicholas; curates came and went at an alarming rate, with one or two exceptions. But it was not all strife; one of the greatest supporters of Nicholas was Francis Mount Durnford, church warden from 1878 until his untimely death in 1898 aged 48 years. His death dealt Nicholas a tremendous blow and he never established the same rapport again with a parish officer. But he might be gratified to know that almost a century later St Stephen’s numbers among its ranks descendents of his faithful warden.

Carter, Sr Emily and Nicholas all lived long enough to see the work at St Stephen’s flourish. Carter died in 1901 aged 93; Sr Emily lived until 1905, and a plaque commemorates her in the church; Nicholas outlived them all. He retired in 1917 and lived until 1932 dying at the age of 95. But after years of conflict over the schools the Sisters can be said to have had the last word. In 1919, two years after Nicholas retired the Sisters removed St Stephen’s College to Folkestone, and the High School took over their premises. It was the final twist and one which Sr Emily, pioneer in the Gravel Pits, would have enjoyed enormously.

Valerie Bonham

Footnotes

- St John Baptist Magazine Easter 1884.

- BONHAM, Valerie “A Complication of Circumstances: Canon Carter and the Clewer Case” in Windlesora No. 8 1989 pp. 15-24.

St Stephen’s High School closed in 1934: St Stephen’s College moved to Broadstairs following evacuation to Taplow Court during World War 2 and finally closed in 1991: the church of Clewer St Stephen is, at the time of writing, part of the Windsor team ministry.

Acknowledgments

I am indebted to the following for help and information: the Community of St John Baptist, Clewer; the vicar and church wardens of Clewer St Stephen; the Misses Osborne; Mr R. L. Bull.