– the building of the Windsor water conduit

Published in Windlesora 21 (2005)

© WLHG

It is a little known fact that Windsor once boasted one of the most elaborate water systems in the country. It provided Windsor Castle, and also probably the town of Windsor, with the first supplies of piped water and would indeed have seemed ‘curious’ to the sixteenth century Berkshire citizen. How was it possible, three hundred years before the invention of the mechanical pump, to have a fountain thirty feet high in the upper ward of the castle — a local high point, itself one hundred feet above the river Thames – producing a gushing water spout a further thirteen feet high? How was the system powered and where did the water come from?

Early water systems or conduits, were installed in the most important medieval towns and many monasteries – mostly for reasons of hygiene, although due to their cost, display and status might also have influenced the decision to build them. They operated purely through the forces of gravity. Typically water was collected from a convenient hill-side spring into a head reservoir that was located at some elevation above the distribution fountain; the pressure contained within the head tank would then force water through a connecting (sealed) underground lead pipe to the fountain. The significant advantage of conduit systems was their ability to transport water up-hill, due to the pressure exerted from the head cistern within the pipe. This allowed conduit systems to cross river valleys or other topographic features without the requirement for expensive aqueducts or water tunnels that were necessary in ‘open channel’ type water systems, typically found in Roman settlements. The first English conduit systems were established in Christ Church, Canterbury dating from 1153 and Waltham Abbey from 1220. The London water conduit, probably the first purely urban system, was operating by 1260 – considered relatively late by European standards; Paris for example, had a system from 1119.

Conduit systems however were often unreliable, the pipes would leak causing local flooding and the springs that fed to systems could run dry in the summer months. As with all technology, over time improvement were made and gradually conduits became better built and more reliable. By the sixteenth century, the great land owners, merchants and bishops all sought to have a conduit water supply diverted into their homes, as extensions from the public system; it was the must-have domestic improvement for the sixteenth century urban rich. Royal palaces were not to be excluded, Westminster palace had a running hot and cold water (and royal bathtub embellished with gold (lattern) taps) from the time of Edward III (1327-77) and Hampton Court had a supply tapped from Coombe Hill. The Windsor conduit formed part of the improvements made to the castle between 1552-9. Unfortunately, when many of these conduits were replaced, the records relating to their construction and management were destroyed — as they were considered at the time of no further relevance. As a consequence the complex technology of medieval conduits has been largely, and undeservedly, forgotten. The Windsor conduit is however unique in England, as an almost complete set of construction accounts has survived, as transcribed in the eighteenth century by Elias Ashmole in the working papers for his volume on the history of Berkshire. These accounts detail how the system was built and explain its princely price tag of over nine million pounds, in current-day terms.

Ashmole’s record starts with the construction work between 24th July 1552 and 12th November in the same year — the construction dates are note-worthy, as it seems that the conduit could only be built whilst the weather was warm enough to both dig the trenches for the pipe and build the furnaces to melt lead, the principal construction material. The system was conventionally designed with a series of tanks at the source springs that fed into a larger head collection cistern. The head cistern was then connected to a single sealed pipe that roughly followed a downward path towards Windsor town; the pipe being laid from head cistern, so that a check could be made as the pipe was installed that water continued to flow. Gravity-fed water systems did not require an exact downward course for the pipe, but experience hadtaught conduit designers to avoid steep gradients where possible, as they tended to increase the rate of pipe fracture by increasing the internal pipe pressure at the point of rapid decent.

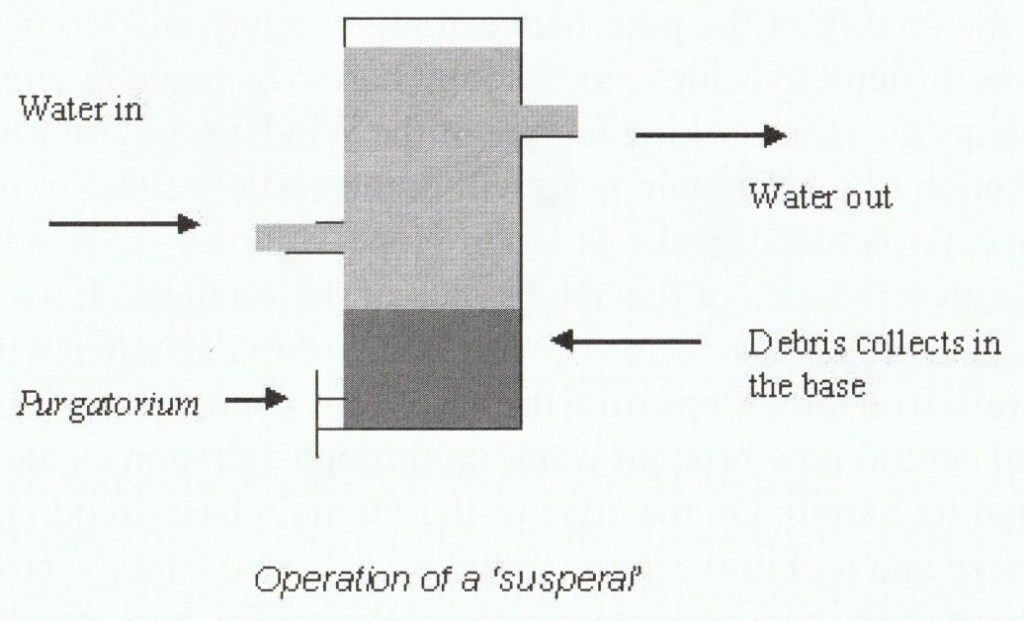

The water for the Windsor conduit system was taken from field springs immediately behind the current site of Windsor Park village, identified on Norden’s map of Windsor district as Cramborne Walk (modern Cranborne), due south of an enclosed area called ‘Suning hill parke’. The water collected would have contained sand and other debris that needed to be removed to prevent it accumulating within the pipe and creating a blockage. The method of performing this task was to insert water cleaning and inspection tank within the course of the pipe. These tanks were given different names by the various conduit designers, but in the Windsor accounts they are called ‘susspalls’; in other systems they have been called suspirel, suspirale, cesperill, spurgel, spurgella or spurgellum.(1) Suspirals worked rather like settling tanks, where water would flow into a sealed chamber through a pipe approximately half way up one side, with clean water being drawn off by an exit pipe on the top of the opposite side, allowing solid debris to fall to the bottom which was subsequently removed either by hand or by a special flushing valve — known as a purgatorium.

The Windsor conduit would have had a fall of about 40 meters from the head cistern to the fountain in the upper ward of the castle and this would have been sufficient to provide a substantial flow of water through the pipe, even allowing for the upward slope of the pipe as it reached Castle Hill.

The path of the conduit pipe towards Windsor can be followed from the accounts. From the conduit head in Cranborne in the parish of Winkfield, the system had a ‘first receipt’ or ‘sesterne’ at ‘Frith Lane, called Kilby Gate’, the pipe was then let down to a second or “middle receipt’ inexactly described as ‘down towards the pond’. From there the water flowed to ‘the place where it is knit to the (unidentified) corner house’, leading towards the ‘Mote park’. At this point, for an unknown reason, conduit building appears to have stopped for two years, although as this date coincides with the death of Edward VI in July 1553 there may have been problems in securing continuing funding for the project. However, In June 1555 the building work resumed, from the Mote park the pipe was laid through ‘Clewere’, Windsor field (le Worth), ‘Ole Pitte’ (Bachelors Acre), the church yard of St John the Baptist, the gardens of the Old House, the castle ditch and finally through the ‘rubbish gate’ of the castle to the upper ward. As the accounts record ‘the pipe (was) bought up into the middle of the court where the receipt of the water shall be, and there the water plenteously did run 13 foote high’.

Book three of the accounts records the building costs of the conduit, such as that of carpenters making ‘the great mould in the plumbery’. The mould referred to would have been used to cast a flat sheet of lead (in a similar process to making roofing lead) that was the starting point for the manufacture of conduit pipes. The method of making pipes changed little throughout the middle ages; the flat sheet of lead, whilst still warm, was formed around a circular core or mandrel to make a pipe that was more pear-shaped than round. The seam joint being sealed with a lead/tin solder. Making conduit pipes was deemed to be an especially skilled task as the plumbers ordinances of 1365, state that working ‘a clove of lead for gutters or roofs of houses take only one halfpenny, for working a clove of lead for belfries and conduit pipes, one penny’. The source of lead for making the pipes in Windsor was substantially the scrap lead from the roofs of ecclesiastical buildings that were being pulled down following the reformation. Initial supplies were obtained from the monasteries of Owebourne, (Ogbourne) Wallingford and Abingdon, with additional supplies from Wallingford Castle, Grafton, London, ‘Maydstone’, the buildings of the former nuns of (King’s) Langley and the roof covering of the south aisle, lady-chapel and vestry of the (suppressed) Blackfriars church, also in King’s Langley. The recovery of previously used building material was not limited to lead; Caen stone was taken from Reading Abbey; Roger Amice is recorded as ‘surveying, viewing and appointing’ the stone and subsequently moving 268 cart loads from Reading to Windsor. Conduit pipes were typically ten to twelve feet in length and up to four inches in diameter and would have been very heavy — but yet required careful support and handling so as not to damage the delicate seam joint. Sections of pipe were transported to the installation site and joined either by simple butt-joints or by flaring one pipe end and inserting the next pipe; the joint being sealed with further solder provided from a mobile furnace located near-by. As the pipe had to be perfectly sealed for the conduit to work effectively, the quality of the joint between pipe sections had to be well made, but often this was difficult to achieve as the joint had to be made in-situ.

Perhaps the most striking feature of the Windsor conduit accounts is the detailed description of the fountain head within the castle walls. From Norden’s 1608 Windsor survey (included in the St. John Hope volumes on Windsor Castle) it is possible to gain some idea of the appearance of the fountain. It was 45 feet across, standing on an eight sided stone base, with lead cistern decorated with heraldic arms in cast lead raised on three steps from the base. Taps poured water into the cistern and an additional central pipe brought water up through a dragon statue that discharged water through its mouth. On the edge of the fountain base stood eight pillars, supporting a frieze and architrave surmounted by a domed canopy, covered with lead. Round the base of the canopy were figures of the griffin, hart, greyhound, antelope, each holding a cartouche of the royal arms and above all this, a lion and an eagle holding between them a great vane with the imperially crowned royal arms of England and Spain. The conduit fountain dominated the upper ward of the castle and was obviously intended to be an iconographic statement, attesting to the power and modernity of the monarchy.

Despite the enormous sums of money spent on the Windsor conduit, it appears to have only worked for about fifty years, as by 1609 the system was reported ‘broken’ and requiring substantial repairs costing £646/10s. It seems likely that the fine sandy soil from the Great Park was finding its way into the underground pipes, blocking the flow of water. Further extensive repairs were again reported as necessary in 1635 and this appears to have been the final straw; and although there was a suggestion of replacing the fountain with a statue of Hercules, the conduit was removed in December 1635.(2) Hollar’s view of the upper ward of the castle made in 1657 has no conduit fountain. The valuable underground lead pipes would have been largely recovered at this time, although exceptionally, a piece of the pipe was discovered in Windsor churchyard in the nineteenth century, whilst a grave was being dug.

The Windsor conduit accounts provide a unique insight into the methods of building water conduits, the iconography of kingship in the sixteenth century and a case study in why gravity-fed water systems, although popular for over three hundred years, were comprehensively replaced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries for systems that were both more reliable and durable.

David Lewis

Notes

- Tighe and Davis confuse the term ‘sesspall’ with cesspool — clearly a cesspool would have no function within a water transportation system. T & D, I, 602.

- St. John Hope, I, p.300