(1796-1817)

Published in Windlesora 34

©2018, WLHG

On 6th November 1817, Princess Charlotte, only child of the Prince Regent, died ‘after a severe effort of nature, which lasted 50 hours in bringing into the world a stillborn male infant‘.

As the time of the birth approached, the Prince Regent, Queen Charlotte and an assortment of Great Officers of State, whose attendance at royal confinements was customary, arrived at Claremont to await the royal delivery, which was expected to take place around 19th October. A week passed and nothing happened. so the assembled company dispersed, Queen Charlotte to Bath and the Prince Regent to Suffolk for some shooting, leaving Sir Richard Croft, the physician-accoucheur and a Mrs Griffiths who acted as nurse.

It was not until 3rd November that Charlotte finally went into labour, those Great Officers who could be contacted, hurriedly made their way back to Claremont. Leopold was constantly at his wife’s side, only leaving the room ‘when delicacy dictated’. Sir Richard had by this time sent for two more doctors, one of whom was his brother-in-law.

At 9 o’clock on the evening of 5th November, Charlotte was delivered of a still-born son. Notwithstanding this, desperate attempts were made to bring the child to life, including rubbing the tiny body with mustard, but he had probably been dead for some hours before the actual birth.

Soon after midnight Charlotte was in agony: dosing her with hot wine and brandy was of no help at all and by half-past two, the heiress- presumptive to the throne lay dead, probably from a blood clot caused by a haemorrhage. Modern medical opinion reckons that Charlotte suffered from porphyria, like her grandfather, and could never have brought a living child into the world.

Leopold was distraught; for some time he would not allow the doctors near his wife’s body and while he lived at Claremont left Charlotte’s cloak and bonnet on the chair exactly where she had put them. (This seems to be a peculiar Coburg characteristic, which was later seized upon by Queen Victoria who practically turned it into an art form.)

The Prince Regent took his daughter’s death badly and was bled by his doctors, the invariable treatment for any kind of affliction – indeed Charlotte was frequently bled during her pregnancy, which must have considerably weakened her. Mourning was nationwide: broadsheets, engravings and china figures were widely sold, commemorating a young woman, heiress-presumptive to the throne, cut off in her prime. She was often depicted with Leopold, who had not only lost his wife and son, but also the prospect of being consort to a future Queen.

Sir Richard Croft had done his best (which the Prince Regent and Leopold readily acknowledged), but even so, allegations of incompetence began to circulate with the result that some expectant mothers looked elsewhere for medical assistance. Three months later Sir Richard was confronted by a similar case and shot himself.

A few days later Banting, the royal undertaker, arrived with 40 of his men to make initial preparations for the funeral. We are told that Charlotte was embalmed (as was the baby) then ‘wrapped in several wax cerecloths and covered with blue velvet’ before being placed in a lead coffin which in its turn was placed in one of mahogany and finally into a state one covered with crimson velvet and silver-gilt decorations.

On the evening of 18th November two hearses set out from Esher followed by Leopold in a closed carriage; in the towns and villages they passed through people stood in silent tribute while the church bells tolled. They arrived at Windsor at 2 o’clock the next morning; Charlotte’s coffin was taken to Lower Lodge (now Burford House) for a brief lying-in- state. The baby’s coffin was taken straight to St. George’s Chapel where eight Yeomen of the Guard deposited it in the Royal Vault without any ceremony.

Arrangements for the funeral were not all they should have been; such was the pushing and shoving to see the lying-in-state that troops had to be called in to keep order. Those citizens lucky enough to get a place in the Chapel were squashed into the north aisle, with so many soldiers in front of them that they saw next to nothing. Charles Knight stated that the undertaker’s men were drunk.

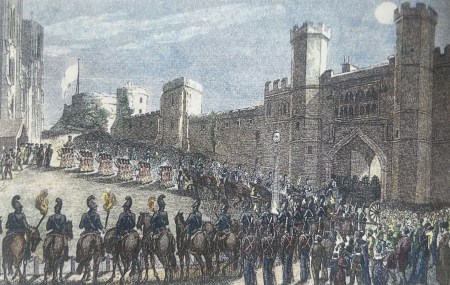

Like all royal funerals at the time, Charlotte’s took place at night, and the cortège set out from Lower Lodge at 8.30 in the evening. Leopold, as Chief Mourner was supported by two of Charlotte’s uncles, the Duke of Clarence (afterwards William IV) and the Duke of York. The Prince Regent, following royal protocol, did not attend.

The service followed a familiar pattern; the burial sentences of Croft and Purcell were sung, as were Psalms 39 and 90. After the coffin was lowered ‘by imperceptible machinery into the vault below‘ the Dead March from Saul was played as the mourners departed. A contemporary aquatint depicts a sea of black, relieved only by the Garter banners and the tabards of the heralds.

Charlotte’s monument in St. George’s Chapel is not only the most spectacular of royal monuments but also the first one of any significance for more than 200 years. It was erected by public subscription, contributions being limited to one guinea (£1.05) per head, which nevertheless raised £15,000. It was at first intended to house the monument in a purpose- built temple or similar structure in a public park (or alternatively in the summerhouse at Claremont), but in the event it was decided to place it in the Urswick Chantry where it was unveiled in 1826.

‘The Princess, says Gunnis, lies covered by a shroud with the fingers of one limp hand protruding to macabre effect. She is attended by four completely veiled kneeling figures, while above the pitiful scene and in contrast, the Princess bursts theatrically from the open tomb and soars upwards, accompanied by two angels, one of whom carries the child’.

It is the work of Matthew Cotes Wyatt, who trained as a painter rather than a sculptor and specialised at first in theatrical design, a skill he uses here with telling effect. Unusually there is no inscription, but at the time everyone would have known whose monument it was. The monument was cleaned and repaired in 1844, when James Bedborough charged £12-5-0 for two pinnacles. Wyatt followed this up with a similar monument to the Duchess of Rutland at Belvoir, equally dramatic, but not so elaborate.

All this meant that there was now a large question mark hanging over the succession to the throne, and so the Prince Regent’s brothers, who were also not married each had to find a wife and produce an heir. Leopold was an important catalyst; his widowed sister Victoria married Edward, Duke of Kent. They had an only daughter, Victoria, and the rest is history.

Leslie Grout

Sources

- Olivia Bland, The Royal Way of Death, 1986

- Shelagh Bond, The Monuments of St. George’s Chapel, 1958 Rupert Gunnis, Dictionary of British Sculptors, 2009

- Fellowes & Poyser, The Registers of St. George’s Chapel, 1957