Criminal justice in Medieval Windsor

Published in Windlesora 27 (2011)

© WLHG

It is often supposed that one feature of medieval Windsor which would never be in short supply was gaol space. The castle, surely, could provide as much accommodation of this type as was required, even if it just amounted to an unsavoury dungeon. In fact, throughout the middle ages the castle was only consistently used as a gaol for state prisoners, and even this use was intermittent. The castle’s primary function, particularly from the second half of the thirteenth century, was as a royal palace, nothing more. It would be wrong, however, to say that the castle never operated as a town, forest or Country prison, it did; but these episodes were brief and confined to its early history.

Unlike the modern arrangement, prisons in the middle ages were only used to hold prisoners before trial, rather than being a means of punishment post trial. For this reason medieval gaols were typically small, consisting of a lockable room or cell with sufficient space for perhaps five detainees. A further distinctive feature of these gaols was their singular attachment to a particular type of court. Courts were organised according to the law they administered and as there were several law codes (church, mercantile, civil, forest and criminal), divided for criminal law into major and minor charges, there were a number of different associated gaols. The county sheriff, for example, would control the sheriff’s court, normally hosted in the county town, with its associated county gaol. This arrangement is demonstrated in many counties, but with the exception of Berkshire. It was far from clear which of Berkshire’s major towns was its county town, and in consequence the county gaol was located in a succession of different towns. Before the mid-thirteenth century, for example, the county gaol could be found in Farringdon (1183), and in the castles of Wallingford (1216) and Windsor (1184/5, 1233/4). Some resolution of this issue was attempted in Windsor’s borough charter of 1277, establishing the town as the county town. But this role was short lived, owing to local flooding, a shortage of food and the difficulty of reaching a town located at the extreme eastern edge of the county. The county gaol was moved in 1315 to Wallingford.

Apart from the county gaol, medieval Windsor was the location of two other courts; a specialist forest court, responsible for the administration of forest law applicable to the royal hunting grounds near the town, and a town court.

The existence of a town court in New Windsor only slowly emerges from the documentary evidence of the twelfth century. It is probably a fair assumption, but nevertheless an undocumented one, that some type of court existed from the date of the town’s foundation in the late eleventh century. This court was likely administered by the Constable of the castle (or more usually his deputy), as he (and occasionally, she) administered the day-to-day operation of the Windsor settlements (Old and New Windsor) on behalf of the king. This official would almost certainly have used the castle for this purpose, including space set aside for a court room and gaol. We know that the castle had a gaol from the earliest days, as the Earl of Northumberland was imprisoned there in c. 1080. At this date the castle, or at least its palisades, were of rather un-prison like timber construction but the existence of the gaol may indicate that its internal structures ‘the kings houses’ were built of stone, in the Norman fashion. We have very little information about the operation of this court in the twelfth century, although by c.1190 evidence for the existence of a separate town court, or folk moot, becomes a little firmer.

The early charters of Waltham Abbey note the existence of this civic solidarity in connection with the parish church of St John the Baptist. The abbey had been given possession of the two Windsor (Old and New) parish churches by Henry II in c.1170, and this might connect with meetings of the folk moot in the church yard. Arrangements of this type have been noted in contemporary towns better documented than Windsor. It is unclear, however, what functions this body exercised. Possibly it advised the Constable (or his deputy) on matters concerning justice or indeed, it may have acted as an embryonic town council. Certainly, it was headed by the Reeve, the town’s most important citizen; an individual noted in the Abingdon Chronicles of 1104. This reference is of significance as it further suggests that Windsor’s folk moot, although first documented in the late twelfth century, had likely existed in pre-Conquest times. The post was transferred to the new castle site, together with the rest of the old town, once royal use of Old Windsor formally ceased in c.1110. By the early thirteenth century the position of the Saxon Reeve had been formalised and renamed the town Bailiff – an Anglo- Norman term, indexing the change in official language from Old English to Norman French.

New Windsor underwent a significant change in its constitution in the mid thirteenth century (c.1240), when its Bailiff (and later two town Bailiffs) assumed the Constable’s powers to operate the town court. This body effectively ran the town, and continued in operation until the nineteenth century, although renamed the ‘mayor’s court’ in the mid fourteenth century, with the introduction of this senior civic post. Significantly, the emergence of this independent town court pre-dates Windsor’s 1277 grant of royal borough status. This suggests that the charter did not mark a decisive change in the town’s operation, as is often supposed, but merely confirmation of pre- existing rights. In fact, the independence of the town was probably more effectively marked by the construction of a new, and the town’s first gaol in 1260. It was the town Bailiff’s personal responsibility from this date to confine certain categories of offenders and to ensure their safe delivery to the justice system, through their control of this gaol.

The order to build the gaol is recorded in the Liberate rolls, but unfortunately there is no indication where in the town the gaol was to be built. Nevertheless, with the aid of other documents, it is possible to speculate. As the gaol is not referred to in any of the contemporary town property deeds as forming an abutment to existing property, it was likely a free standing structure. Judging by other towns, it would probably have been situated close to the town court, and this might place it near Windsor’s market place, close to the castle gates. A room over the Castle barbican large double-gated structure replaced by the existing Henry VIII gate in 1509 – is known to have been used as a court room in the early fourteenth century. The exact form of this gaol is unknown, although as timber was ordered to be taken from Windsor forest for its construction, it was likely a single storey timber framed building, typical of other buildings in the town. We have no direct information about those who may have been responsible for its upkeep, a gaol guard perhaps. A note made in the sixteenth century town accounts for a payment to an over-night prison guard suggests there was never a full-time position of this type. Possibly, a guard was recruited only when a prisoner was considered particularly likely to escape. Another possibility is that the hereditary post of town pillory-keeper, as one of the very few medieval paid town officials, would have been additionally responsible for the gaol. We know the first recorded member of this family, Ivo Pillori de Wyndesore, lived in nearby Peascod Street before c. 1242, and this may suggest some connection.

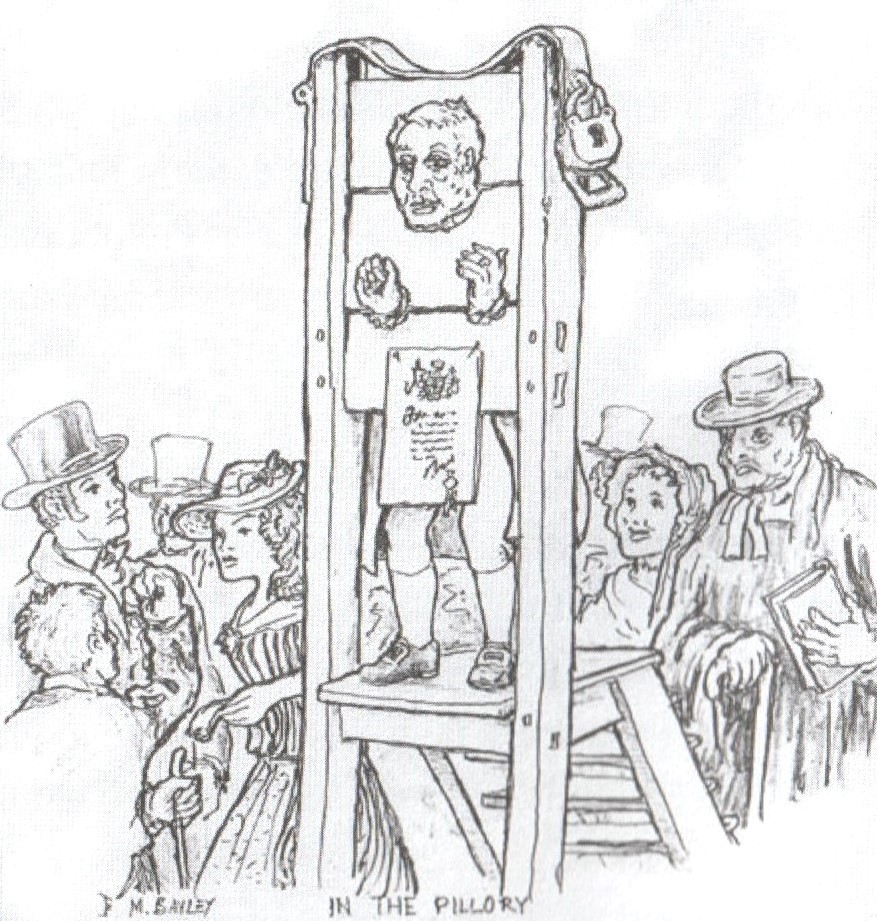

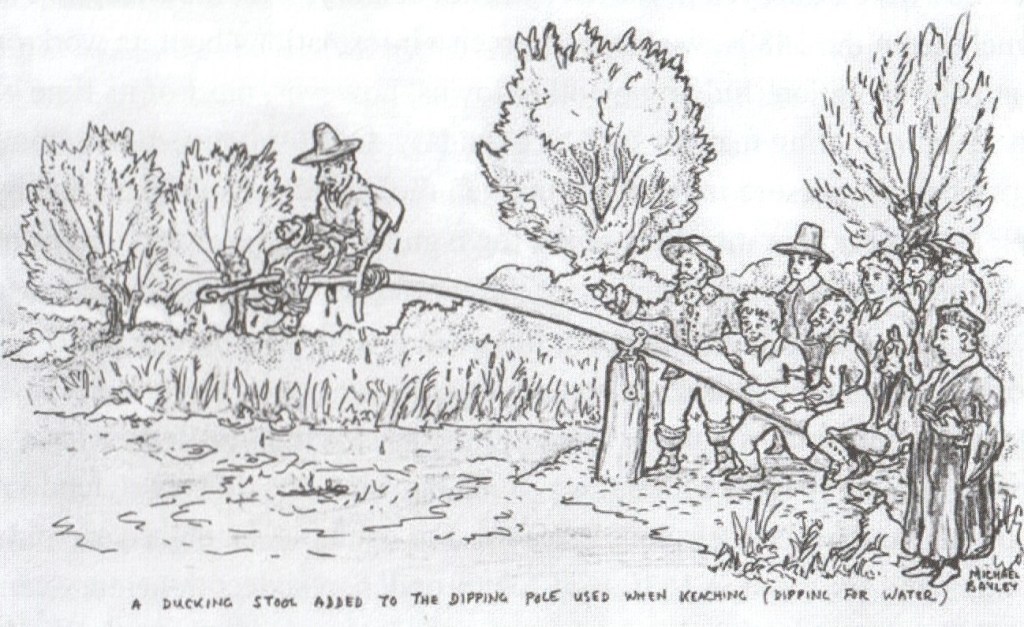

As the name of this official indicates, one of the punishments ordered by the court was to be locked in the town pillory – a punishment likely reinforced with a fine, whipping or typically some other form of public humiliation. We know from seventeenth century drawings of the town that two pillories were located between the site of the current guildhall and the parish church (new built 1612) and this seems to have been their location from the earliest times. The first record of the pillory (and tumbrel) in Windsor is noted in the Liberate rolls in 1272 when 3s. 6d. was paid for their repair. The pillory was used to punish men for minor misdemeanours, whereby the neck and wrists were locked together so that the offender became a target for items thrown by passers-by. As the pillory was located near the market-place some of these missiles would likely have been very unpleasant, and probably it proved an effective means of a settling old scores between town rivals. Women, on the other hand, would be punished by sitting in an elevated chair (a tumbrel) near their home, also being subject to the taunts of their follow townsmen. The town also operated a ducking stool for women offenders, as its cost is noted in the town accounts, but we have no information about its use.

The Bailiff’s court would have tried all local civil disputes and minor criminal matters, with the exception of serious criminal offences involving blood, such as murder. Crimes of this type were reserved to the king, and were tried by the itinerant royal justices. Punishments ordered by this court included hanging, which in medieval Windsor was carried out in a field now occupied by the castle gardens, originally called, rather graphically, ‘La Lynch’. Permanent gallows were erected in this field, within sight of the road between Castle Hill and Datchet ferry, with sufficient space for gatherings of townspeople who might come to watch the punishment being carried out. Timber and nails to maintain the gallows are a feature of the town accounts throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth century. In addition, an inventory of the guildhall taken in the fifteenth century notes the town’s ownership of a hanging rope and gallows lock – presumably the device used to secure the rope whilst in use – confirming the town’s (or more exactly, the Bailiff’s) responsibility to carry out the orders of the court. Although the Lynch field was the usual place of execution in the medieval town, in special circumstances, and when extra publicity was required, other locations might be selected, such as the castle bridge or Windsor Bridge.

Windsor town court met on a frequent basis, probably weekly, but as its records were destroyed in the seventeenth century, with the exception of a fragment from the 1480s, we have no precise information about its work or its mode of operation. Judging by other towns, however, most of its time was likely spent resolving matters such as boundary disputes between neighbours, claims of short measure in the town market, the illegal use of the market by ‘foreigns’ (traders not members of the town guild) or in resolving claims of slander between townspeople. Few of these offences would warrant the use of the town gaol, and still less hanging, but most would have involved the imposition of a nominal fine, or an oath to keep the peace. Despite the loss of the town’s court rolls, a number of punishments exacted in Windsor have survived in other records of the town. Such punishments, however, tend to be exceptional and hence their double record. For example, an eight-year-old boy was hung for arson in 1630, and John London, a sixteenth-century canon of St George’s was tied facing backwards on a horse to ride through Windsor, Reading and Newbury, being pilloried in each town (see the article about the Windsor Martyrs for the reason for this punishment). Although we like to think of the Middle Ages as being barbaric, such cases are far from typical. An impression of the more usual punishments might be gathered from the nineteenth century quarter session rolls, where those convicted of petty theft would be whipped through the market place for a hundred yards.

As the Bailiffs were personally responsible for the safe custody of prisoners, it was considered a serious matter if any prisoners managed to escape. This was of particular concern if the prisoner was awaiting criminal trial, as the Bailiff would then be subject to the king’s justice in place of the accused. Several occurrences of this type are noted in the patent rolls, with the escaped prisoners typically seeking protective sanctuary in Windsor’s nearby parish church. The problem of escape, however, was likely difficult to counter owing to the insubstantial nature of the prison building and the absence of a dedicated full-time gaol guard; Windsor gaol must have represented little challenge to a determined escapee. Windsor Bailiffs were charged with negligence if the prisoner actually escaped, and normally punished with a fine, nothing more.

It may have been to avoid the embarrassment of escape that it became the practice to manacle prisoners while in gaol. Manacles and chains of different types are noted in the fifteenth-century guildhall inventory, together with ‘pins‘ to lock the stocks; a further device used to prevent prisoner escape. Typically the stocks, which locked the legs together at the ankles, were kept within the gaol, despite modern examples of the device which confuse its use with the out-door pillory.

We have little information about Windsor’s court and gaol in the early fourteenth century, but with the town’s growing wealth as a result of Edward III’s building campaign in the castle’s upper ward from 1349, a replacement was considered necessary. In consequence, a prestigious combined guildhall and gaol was built on the market place in c.1351/2. This structure was a significant status symbol for the town, as few could afford such civic buildings, especially given the turmoil – and economic depression – experienced in the wake of the Black Death.

From the medieval town property deeds it seems that although the guildhall and gaol formed a single inter-connecting structure, the gaol was nevertheless capable of operating independently. Almost certainly it consisted of a separate building with its own entrance in Priest Street (now St Alban’s Street), as the gaol is mentioned the deeds of other properties in the street. This guildhall was replaced in 1690 by the existing (Thomas Fitz) guildhall, and although the old building was temporarily used for other civic purposes, it was mostly demolished in 1724. The gaol continued in use for over four hundred and fifty years, surviving the destruction of the medieval guildhall, finally being replaced in 1804. At this date a new prison was opened in George Street (now Windsor Central Station). It is perhaps surprising that the town gaol, together with several other important buildings from the medieval town: the parish church (b.1170), the town leper hospital (b.1252) and several of its once numerous inns, survived until comparatively recently. Unfortunately, all these buildings were pulled down in a rush to modernise. Surely, a lesson from history we could apply to the modern town.