A Georgian Building and a pocket full of Personalities

Published in Windlesora 27 (2011)

© WLHG

‘Any visitor to an historic country town or city quickly becomes aware in his or her peregrinations that the most attractive houses in the centre are invariably the offices of lawyers‘ – PD James, Holy Orders.

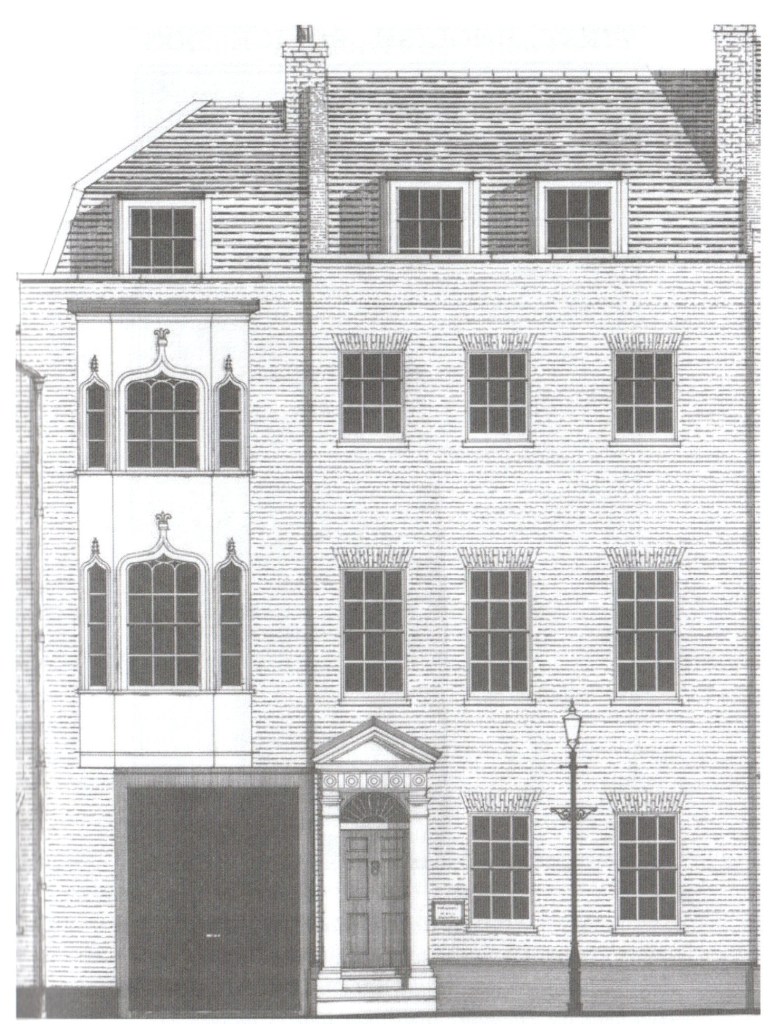

Number 4, Park Street, Windsor, which nestles close to the Cambridge Gate into the Long Walk, almost opposite the Two Brewers public house, is just one gem in a street which, even today, aspires to a touch of commendable elitism, both as to the residencies on the north side and to the various professional practices and offices on the south. It is one of the two or three oldest streets in Windsor; known in medieval times as Moor Street, a gallows stood menacingly at its junction with the High Street. Subsequently, it metamorphosised into Pound Street when the Town Pound for corralling stray animals was situated there, before becoming Park Street in the eighteenth century.

Numbers 4 and 5 Park Street were, according to Angus McNaughton in his Windsor and Eton in Georgian Times, built in 1773 for a Mr Edward Thomas of St James’s Palace, number 6 Park Street being built at the same time. They are notable for their fine doorways encapsulating Doric pilasters and interiors. Even in the twenty first century they retain much of their higgledy-piggledy character. Mr Datchery, in search of lodgings in Charles Dickens’s The Mystery of Edwin Drood would have approved: ‘Something old is what I should prefer, something odd and out of the way; something venerable, architectural and inconvenient‘.

In the eighteenth century and before, Park Street continued across the Long Walk and constituted the beginning of the high road to London. Park Street was a rendezvous for coaches, one of the coaching inns being the Black Horse, which stood at the rear of numbers 4 and 5 and gave its name to Black Horse Yard, which later constituted an office car park.

In 1861 the solicitor George Henry Long occupied number 4 Park Street where he and his wife were looked after by three servants. Born in 1818, he had entered the office of his solicitor father at the age of fifteen when the practice was carried on from a property in St Albans Street. Later, the office moved to his Park Street residence from where he ultimately moved to Beaumont House in St Leonard’s Road. Thereafter 4 Park Street continued as his firm’s offices. In 1877 Long went into partnership with Philip Lovegrove, and Edward Durant joined the firm in 1900, the year of Long’s death, at which date it became Lovegrove & Durant. It was said that Long hardly ever took a holiday from the day he joined his father’s firm. He became Town Clerk and, controversially, simultaneously Mayor, besides being an Alderman of the County Council, the Chairman of the Royal Windsor Gas Company and owner of the Theatre Royal. He was knighted as Mayor in the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee.

The partnership between Durant and Lovegrove ended with the latter’s death on 8 March 1912 and for the next twenty years Durant carried on the practice on his own with considerable distinction, acquiring a host of prestigious appointments on the way. From 1900 until 1929 he was Town Clerk of Windsor, ‘an office which‘, observed the Windsor & Eton Express when reporting his death and funeral in 1945, ‘he filled with dignity, charm and integrity’. For lengthy periods he held numerous positions including that of Clerk to the Windsor Bench, followed by appointment as a Justice of the Peace, President of the Royal Albert Institute, Vice President and Vice Chairman of the King Edward VII Board of Management, Chairman of the Constitutional Club, Chairman of the Governors of Windsor County Girls School and Vice Chairman of the Governors of Windsor County Boys School. He was President of the Berks, Bucks & Oxfordshire Law Society in 1919 and was admitted as a Member of the Royal Victorian Order in 1930. He was prominent as a Freemason and as solicitor to the Princess Christian Maternity Home, the Windsor Fire Brigade, the Windsor & Eton Permanent Benefit Building Society, the Windsor Royal Gaslight Company and various insurance companies, together with the Eton Excelsior Rowing Club, the Conservative Club and the Windsor & Eton Bowling Club. He was a Trustee of not a few charities.

Cecil Durant played a leading role in the acquisition of a suitable vessel for the Windsor & Eton Sea Cadets, which had been formed in 1899 as the first of such Units in the country. Durant’s father, Benjamin, was also a solicitor, who hailed from the West Country. Durant père’s offices were in that portion of St Albans Street, adjoining the Royal Mews, which were demolished in about 1935. Here, as Sir Owen Morshead, Royal Librarian, put it in his appreciation, ‘The son was initiated into the mysteries of the Law’. He qualified in 1886 and carried on the practice alone after the death of his father in 1892. In those days, as the leading legal firm in Windsor, Long Durnford & Lovegrove, practised in 4 Park Street. As to Sir George Long, Sir Owen recorded that he ‘was able to conclude his entry in Who’s Who with the gratifying announcement that he owned one hundred and sixty two acres and two hundred and forty-eight houses‘. Probably many of these properties were held by him as a Trustee and he was certainly of considerable influence in the administration of the Clewer and Vansittart estates, which were clients of the firm, their remnants throwing up interesting conundrums even in the late twentieth century.

Durant migrated from the house in which he was born in Clarence Road (which in due course became part of the Princess Christian Nursing Home) in 1896 when he acquired Clewer Court, formerly the farmhouse of the Vansittart Estate. After Durant’s death the old house fell victim firstly to progressive neglect and then to the fashionable urge for destruction. Remnants of its ruin now lie beneath the Windsor Leisure Centre.

Durant married a Miss Brown, a daughter of the old-established Eton tailoring firm of Tom Brown, hard by Barnes Pool Bridge. By her he had one daughter, who became the wife of the leading medical practitioner in the town, Dr Edmund C Malden. As Sir Owen Morshead wrote, ‘he was a Windsorian root and branch‘. The Windsor & Eton Express under the heading ‘Death and Funeral of a Former Town Clerk of Windsor‘ reported ‘Mr Cecil Durant passes away at the age of eighty one years: a well known character in the Royal Borough for over sixty years‘. There were weighty tributes; Sir Owen again: ‘A solicitor who rarely advised litigation; this gentle and upright character‘. The newspaper devoted over fifty inches of column space to its report, an expression of respect which it might be doubted had ever been equalled before for a local solicitor and would certainly never be again.

Bound inextricably into the life of number 4 was a clutch of solicitors’ clerks, almost Victorian in their efficiency, loyalty and independent outlook.

Of these stalwarts of a virtually vanished breed, J W Hutchinson was an outstanding example. A eulogy written by one of the partners on his death in the early 1950s is worth the quoting:

With the passing of Mr JW Hutchinson Windsor has lost yet another of those sterling characters who were born and bred in the golden autumn of the Victorian age, an epoch which has so entirely vanished that it seems hard to us who never knew it to realise that there are people still alive who lived in it and who still unconsciously measure their standards in part by their early experience of its solidity and security.

James William Hutchinson was born on the 9th April 1878.

At the age of 14 he left school to enter the Office of the late Mr EC Durant who then practised as a Solicitor in St. Alban’s Street. In 1900 Mr Durant joined the late Mr Philip Lovegrove in his practice at 4 Park Street Windsor and young Hutchinson came with him. He has worked in that Office uninterruptedly (with the exception of his period of service with the Berks Yeomanry during the 1914-18 War) ever since.

It is a wonderful record of devoted service and we at the Office will miss him sadly. He was, as might be supposed, a mine of information upon all local subjects and used to delight in retailing anecdotes of his early experiences and of bygone Windsor figures.

Hutch, as he was known, was succeeded as cashier by Tom Pinder, whose hours were from 10.00 am to 4.00 pm, since with his fine voice he was also a Lay Clerk at St George’s Chapel and his first priorities were to the Chapel Services. Mr Pinder – nobody in the office was so familiar as to call him ‘Tom‘ – affected a somewhat critical demeanour and was an expert at metaphorically raising his eyebrows. His account books were in his own meticulous handwriting, such was the level of administrative sophistication in those days.

Mr Pinder conducted this side of the firm’s business from the front office at 4 Park Street, furnished with high antique oak desks, at which he and an assistant sat on lofty stools. The whole scene, down to the coal fire, which burned in an ancient grate, could have been lifted from one of Cruikshank’s drawings in the novels of Charles Dickens.

Laurence Whitelock, aged about 30, was, from shortly after WW2, manager of the firm’s probate department. He was unmarried and lived in lodgings in Bexley Street. His home was in Penrith, where his mother lived and where his six brothers and sisters also resided. He was exceedingly hard – working, helpful and intelligent.

Laurence Whitelock had a severe limp. This deficiency, coupled with his inability to swim, doubtless contributed to the tragedy on the 4/5 June 1955. Walking home in the dark with a group of friends from the Eton Fourth of June Celebrations, along the promenade just above Windsor Bridge near the Old House Hotel, a girl in the party missed her footing and fell into the river. Without a thought for his own safety, and regardless of his disability, Whitelock jumped in to try and save her. The tragedy was complete: both were drowned.

As an epitaph for Laurence Whitelock, one can do no better than go to Agatha Christie’s autobiography: ‘Loyalty and courage are two of the finest things there are. Any kind of courage, physical or moral, arouses my utmost admiration. It is one of the most important virtues to bring to life.‘ Loyalty was the hallmark of his life and courage was the hallmark of his death.

Miss Violet Schofield was the senior secretary with the firm for over fifteen years. Before arriving at Lovegrove and Durant she had for many years been secretary to Mr Beckwith, Headmaster of the old Imperial Service College, leaving only on his death. When the senior partner needed a secretary in about 1942, she was therefore delighted to accept the position.

Miss Schofield’s family came from Westward Ho! on the North Devon coast, where the Imperial Service College, then known as the United Services College, was situated before its translation to Windsor, where in 1911 it amalgamated with the St Mark’s College (which establishment had earlier given its name to St Mark’s Place and St Mark’s Road). In 1911 it became the Imperial Services College.

When Rudyard Kipling came to write his novel, Stalky & Co., he was inspired by his unhappy school days at the United Services College. Into the novel he injected various real-life personalities. Major General LC Dunsterville became the Stalky of the title, and one of the others was none other than Violet Schofield’s father who appears in the book as Sergeant Instructor.

Towering above them all was Jack Barker although nobody but the senior partner would have dared address him as other than Mr Barker.

There used to be a feature in the Readers’ Digest headed ‘The Most Unforgettable Character I Ever Met‘, and Mr Barker would come close to being the author’s nomination for this adulatory accolation. To generations born before WW1, AJB referred to Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister and nephew of the great Lord Salisbury. To those who had anything to do with the law in East Berkshire after the Second World War, and many who hadn’t, AJB meant exclusively Arthur John Barker. To partners, staff and clients he was a force to be reckoned with.

Mr Barker joined the firm in 1936, almost from school after a brief period with a firm of builders. The oft-told story was that he first approached a rival firm by whom he was offered the position of office boy at 1/- per week less than he believed himself to be worth. He therefore applied to Lovegrove & Durant where he was engaged by Cecil Durant, the senior partner, who, with great foresight, agreed to the extra shilling. That other firm ever afterwards bemoaned their misplaced frugality.

It quickly became apparent that Lovegrove & Durant had gained the services of one who, even at that age, swiftly displayed those characteristics, which never left him, of loyalty, fairness, integrity, sustained hard work and a gargantuan fund of common sense. During the war he served with the RAF in Egypt, where he suffered from a bout of malaria. Egypt gave him no taste for foreign travel. He never went abroad again. ‘England is enough for me,’ he said, but as he hardly ever took a holiday the comparison was, perhaps, academic. Returning to the office after demobilisation in 1945, he began his long and fulfilling reign in his large second-floor office. Nothing fazed AJB. His knowledge, which he carried in his head, of the titles to most of the real estate in Windsor and, indeed, in the surrounding countryside, was phenomenal and conveyancers from other firms would ring him up to seek his advice. When answering Preliminary Enquiries or Requisitions on Title from a purchaser’s solicitors, he would not, if he deemed the question inept, refrain from replying in the most contemptuous and virulent terms so that the partners were accustomed quietly to check such documents before dispatch and, if desirable, tone them down.

All his views were forthright and expressed with vigour. At such times his rubicund features would acquire a deeper hue. Since he knew his subject through and through, the targets of his scorn from top to bottom, knew better than to challenge his diktats. There is some truth in Trollope’s character, ‘Mr Walker’, in his perceptive remark in The Last Chronicle of Barset to the Rev. Mark Robarts: ‘The Clerks often know more than the partners‘. He spoke with a true old Berkshire burr which never altered.

AJB’s explosions never lasted for long and he would be back to his normal equable self. The secretarial staff, all of whom he indiscriminately called ‘Ducks‘, regarded him with great affection and were not above pulling his leg at carefully selected moments.

AJB retired in 1979 at the age of 65, only to turn up again as usual in the office next day announcing that from now on he would come in at 8.30am instead of 8am. He continued to work until 1999, when increasing problems with his leg and a mild heart attack forced a final retirement at the age of almost 85. He died in 2001.

As was said of Sir Thomas More, he was ‘a man of singular virtue and of a clear, unspotted conscience‘.

All these individuals shared with number 4 itself a solidity and an integrity which, in many ways, the modern world has passed by. To have worked there with them and many others was a privilege and a delight.

John Handcock

(The author was with the firm for 48 years as, successively, assistant Solicitor, Solicitor, Partner, Senior Partner and Consultant.)

Acknowledgements

Are appreciately due to the late Angus MacNaughton for nuggets from his book Windsor and Eton in Georgian Times.

And to Mr David Handcock MCIAT for permission to reproduce his architectural drawing of 4 Park Street.