Published in Windlesora 14 (1995)

© WLHG

February 1995 witnessed an unprecedented demonstration against the continued closure (over 130 years on) of the towpath by the River Thames where it passes through the private grounds of Windsor Castle.

In April the Ramblers Association (representing 104,000 members) unanimously passed a resolution at its annual conference calling on the Queen to allow the path to become a part of the Thames Path National Trail which, it is planned, will be opened in June 1996. For centuries the Thames towpath – its distance from Putney to Lechlade is 132 miles – was an accepted public way. Then, as a sequel to the permission given to the South Western Railway to come into Windsor across Home Park, that part of the towpath which remained within the private part of the Park was effectively closed to the public in 1849. As Gardener, solicitor to the Crown Commissioners said at the parliamentary enquiry on the Windsor Extension Railway the Crown was given power to “‘stop up the towpath against all the world but the Thames Navigation Commissioners”. The closure of the towpath was confirmed in 1860.

So the situation remained until recent years. The growing movement to open up the countryside to public access and to create long distance walks has stimulated opposition to what are seen as barriers to this freedom. The proposals to establish a Thames Walk have seen the Windsor section as an important ‘missing link’, in fact the most important missing link. These feelings have reached a climax in the demonstration of February 19th and the Ramblers Association resolution of April 8th.

Every historical event has a context. And this particular event – the closure of the towpath – needs to be seen in a wider context: a context of interest and significance.

For hundreds of years the parkland surrounding the Castle was crossed by public ways. Most important of these, one of the main roads from Windsor to London continued from Park Street (Pound Street as it is called in 18th century maps) across the Park by way of Frogmore. It emerged where the gates are now situated opposite the Lord Nelson Inn and continued through Old Windsor and Staines. Much nearer to the Castle was the way to Datchet, continuing the line of route from Peascod Street by way of Castle Hill, passing within a few yards of the Castle itself and proceeding across the Home Park to Datchet. Both these ways are shown clearly, for example, on Collier’s Plan of the Town and Castle of Windsor and Little Park and College of Eton 1742 and, even earlier on Norden’s Survey of 1607.

A new situation arose in the 19th century. The Crown, the Windsor Corporation and the railway companies which aspired to reach Windsor all played a part. The Castle had been transformed in the 1820s and 1830s and, when Prince Albert came to Windsor upon his marriage to Queen Victoria in 1840, he brought his logical German mind to bear on the possibilities of improving the Castle’s environment. One such possibility was the removal of the houses that lined the Castle ditch. Another was certainly the closure of the public ways that traversed the Castle grounds. He was not averse to railways in general – he used the Great Western from Slough to Paddington from 1839. But, so far as Windsor itself was concerned, he probably echoed the Queen’s determination never to give her consent to a railway line between the Castle and the River.

The Windsor Corporation also had a deep interest. In 1835 the Municipal Reform Act had substituted an elected Council for the ‘self-perpetuating oligarchy’ of the former ‘close corporation’. The Hall Book – the Minute Book of the Guildhall Council meetings thereafter shows the anxiety of the Council to make progress in street improvements, the clearance of slums, and sanitary measures. Many too could foresee the benefits railways could bring to Windsor. But the Town could do little without the good-will and support of the Crown.

Both Crown and Town needed money for the improvements they contemplated. The cost of the reconstruction of the Castle caused a public outcry and the Crown hardly dared to approach Parliament for further financial assistance. The railway companies were to supply the answer. But both before and after Prince Albert’s arrival in Windsor the Crown, as we have seen, had been opposed to the railways coming to Windsor – especially if it meant crossing Crown land.

By slow stages the South Western approached Windsor. From Waterloo it proceeded via Richmond and Staines to Datchet, and then to Black Potts on the opposite side of the River to the Castle. Here, at the ‘station in the field’, the line halted. As late as May 1848 the Crown let it be known that “it was clearly stipulated that the promoters of the South Western line should not extend it over the river into Windsor”. Yet by August the announcement was made that “Her Majesty had graciously consented to an extension of the Windsor, Staines and South Western line from Datchet across the Home Park into Windsor“. In 1849 both the South Western and the Great Western reached Windsor, with termini beneath the Castle walls.

As a result of the negotiations the Railway Companies paid the Crown £85,000. The Corporation also benefited. So the railway companies, directly and indirectly, helped to pay for (a) the completion and the widening of High Street and Thames Street; (b) the demolition of the George Street slum (on the site of the Western Station) and of the remaining houses in the Castle Ditch; (c) the construction of new roads from Windsor to Datchet, from Datchet to Old Windsor and from Old Windsor to Windsor (Albert Road), as well as two new bridges – the Victoria Bridge and the Albert Bridge – in place of the old Datchet Bridge which was demolished; and (d) the drainage schemes both for the Castle and for the Town. As part of the general re-development of the former ways from Windsor to Frogmore and Old Windsor and from Windsor to Datchet by way of Castle Hill were stopped up.

But how does the closure of the towpath fit into this tangled web? In spite of all that the Queen had said the railway across the Home Park had come between the Castle and the River. So had the new road from Windsor to Datchet. The outcome was the creation of the Home Park (Public) as distinct from the Home Park (Private). The Queen gave her sanction for the use of a great part of the Home Park between the new road and the railway for recreation. But the privacy of the Home Park nearer the Castle was ensured not only by the closure of the hitherto public ways but by the effective closure of the towpath.

This is the background to the present controversy. Perhaps this is as far as the historian is required to go. Two possible solutions, however, have been suggested. After the February demonstration it was reported that the Crown Commissioners, pleading security consideration, refused to allow walkers on the land and offered to set up an alternative path on the Datchet bank.

But how does the closure of the towpath fit into this tangled web? In spite of all that the Queen had said the railway across the Home Park had come between the Castle and the River. So had the new road from Windsor to Datchet. The outcome was the creation of the Home Park (Public) as distinct from the Home Park (Private). The Queen gave her sanction for the use of a great part of the Home Park between the new road and the railway for recreation. But the privacy of the Home Park nearer the Castle was ensured not only by the closure of the hitherto public ways but by the effective closure of the towpath.

This is the background to the present controversy. Perhaps this is as far as the historian is required to go. Two possible solutions, however, have been suggested. After the February demonstration it was reported that the Crown Commissioners, pleading security consideration, refused to allow walkers on the land and offered to set up an alternative path on the Datchet bank.

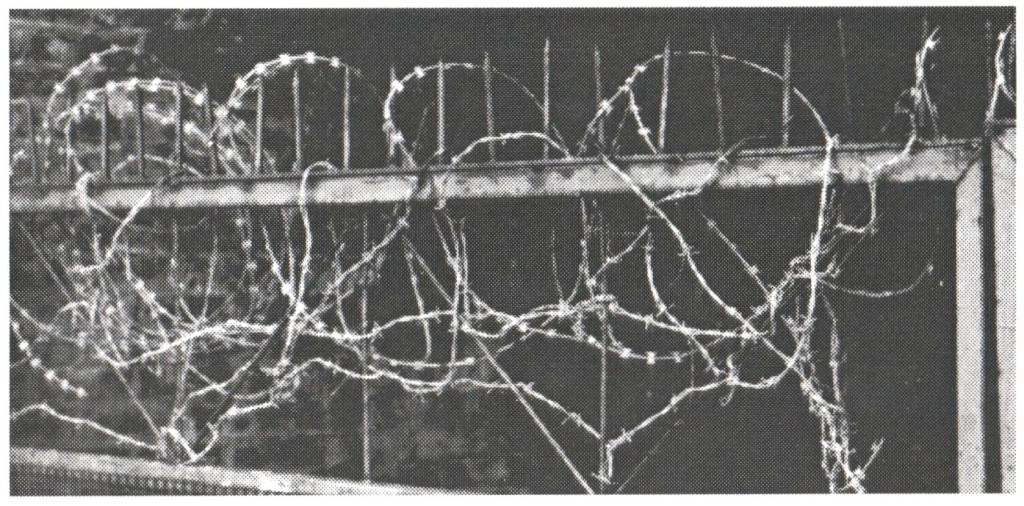

The Ramblers Association, at its annual conference, urged the Queen to allow the path to become part of the Thames Path National Trail. Whether this refers only to the historic towpath through the Castle grounds and allows no room for compromise is not clear. The representative of the Crown Estates put the point of view that “the footpath on the Datchet side will allow better views of the Castle and Park without any unnecessary obstacles“, such as a high security fence. Presumably the Crown Estate Commissioners, the Countryside Commission, the Berkshire County Council and the National Rivers Authority have had this in mind in their discussions. It seems unlikely, however that such an alternative footpath will be able to keep to the riverside for more than a part of the one-and-a-half miles between the present Victoria and Albert Bridges, so we must await developments.

Raymond South

Author’s Note

I have relied for much of the material for this article on two of my books, The Book of Windsor (1977) and Crown, College and Railways (1978), in which references are detailed, together with the Introduction to the Fifth Hall Book of the Borough of New Windsor (1974). I acknowledge with thanks the help of Judith Hunter, Stanley F. Jones, Jack Neave and Margaret Whitelaw.