Published in Windlesora 34

©2018, WLHG

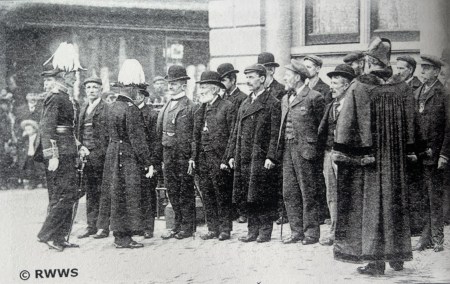

When John Statham stood smartly to attention outside the Guildhall in 1903, waiting for Lord Roberts, he was 81 years old. A retired career soldier, he had experienced horrors we cannot imagine. This was a time of hand-to-hand combat, bullet and bayonet, it was bloody and brutal.

John Statham joined the army at the age of 21 and sought his discharge after more than 21 years of service. His career took him to India, where he saw action in some of the most famous and bloody campaigns and battles, witnessed terrible atrocities, while soldiering with more than one regiment. We do not know which soldier he is in the photograph, perhaps the one with the white beard in front of Lord Roberts, but it is certain that he is one of the oldest.

Born on 25th June 1822 in Whittington, Staffordshire, to John and Dorothy Statham, he was baptized on 5th August, at Wade Street Chapel in Lichfield, some four miles walk away, by the minister William Salt. This was a Congregational Church, called thus because the decisions were not made by the minister or a bishop, but by the congregation. Congregationalists suffered persecution, and the Lichfield chapel had a secret door behind the pulpit so that the minister could escape should there be an attack. It is a challenging start for a child.

He joined the army on 8th September 1843 and became Private John Statham of the 17th Foot Regiment, a year after the end of the First Anglo-Afghan War in which the regiment had fought. On 31st January 1847, he was transferred to the 78th Foot, and served with them until 31st October 1859. In 1857, the 78th was posted to Persia and John fought at the Battle of Khusab on 7th and 8th February, defeating the Persians. Afterwards the regiment marched to Bushire under the most appalling conditions. Torrential rain turned the ground to deep mud which was extremely difficult to get through, pulling soldiers’ boots from their feet for example, making it a tremendous physical ordeal. As Sandes describes in Indian Sappers and Miners (1948):

The troops had covered 46 miles in 41 hours to meet the enemy, a further 20 miles over the most difficult country during the night after the battle, and after a rest of 6 hours, another 24 miles to Bushire.

John and the regiment reached Bushire on 10th February, but not long after this they returned to India in response to a mutiny by Indian troops.

The Indian Mutiny 1857

The summer of 1857 saw violence, perpetrated by the Indians and the Britons, on an unprecedented scale. Never before and never after in the history of British rule in India was there violence at the level that 1857 witnessed.

Rudrangshu Mukherjee, Historian

On 10th May 1857, a group of Sepoys in the garrison of Meerut mutinied and the uprising spread quickly, though not all Indian troops or regiments rebelled.

Cawnpore

By late June, the British garrison at Cawnpore, including women, children, and civilians, had endured three torturous weeks of siege in blistering heat. They were desperately short of ammunition, food, and medical supplies, were under constant bombardment, and faced the very real prospect of starvation. Disease spread through the barracks, and the stress sent some insane. Help from nearby garrisons was impossible as they too were fighting the rebels, so Sir Hugh Wheeler, the 67 year old commander of the garrison, was in a desperate situation. With close to a thousand sheltering in the barracks, he had no choice but to accept a rebel offer that allowed the Garrison to leave under safe conduct down the River Ganges to Allahabad. He surrendered on 24th June, but the evacuation ended in a double massacre. The men and some women were killed at the river; the remaining women and children, altogether some 200 souls, were taken to the Bibighar. The insanitary conditions killed some, but they were the lucky ones; as a rescue force approached the decision was made to kill the rest. Local butchers went to work with cleavers.

Although vastly outnumbered, Cawnpore was recaptured in July, with the 78th instrumental in the action. The brutal scene that met John Statham and his fellow soldiers was gruesome. Everywhere inside the Bibighar was strewn with women and children’s clothes and hair, and the tree nearest the well was drenched in blood. Then the troops found the courtyard well filled with bodies. They were horrified and enraged. The news reports shocked Victorian society, and incensed the rank and file, giving birth to the battle cry ‘Remember Cawnpore!‘

Lucknow

We cannot imagine the effect on men like John Statham, but he and his fellow troops had no time to dwell. They were just 48 miles from besieged Lucknow. General Henry Havelock attempted its relief three times between 20th July and 11th August but failed. He returned to Cawnpore which was again under threat. Major General Sir John Outram arrived with reinforcements on 15th September.

The Lucknow situation was worsening, so he resumed the relief on 18th September. After driving the rebels from Alambagh, they moved towards Lucknow on 25th September. The monsoon rains had flooded the ground around the city, so John and his comrades were forced to fight through narrow, heavily defended streets. It was brutal. From a force of 2000, some 535 men were lost. Most were killed on this last push to the Residency where the garrison, plus 1280 non-combatants, including hundreds of women and children, had withstood a siege of 87 days. Their fighting number had fallen from 1720 to 982.

Outram’s original plan to evacuate was rendered impossible by the heavy losses as well as the wounded, sick, women and children. His discovery of two month’s worth of supplies convinced him to remain. John Statham and the rest of the 78th, joined with the remnants of the Residency’s defenders. Subjected to incessant musket and artillery fire, they kept the rebels at bay for another six weeks, whilst also contending with attacks from below ground. Some 20 mines were dug; seven were tunnelled into by the British and taken over, seven were blown in, three caused loss of life, and two did no injury.

Relief of Lucknow

On 14th November, the new Commander-in-Chief, Sir Colin Campbell commenced his relief of Lucknow, but decided on a different route (see map left). They met no resistance until Dilkusha, but by mid-day the rebels were driven back into Lucknow. On 16th November the column advanced to the Secundra Bagh. Heavy casualties were sustained before men from the 4th Punjab and the 93rd Highlanders pushed forward. The Highlanders poured in through a wall-breach shouting, ‘Remember Cawnpore! At Shah Najaf, unremitting Sepoy fire and failed attempts to breach inflicted more heavy losses on the British. A small party of Highlanders finally entered and opened the main gate. By nightfall Shah Najaf was Campbell’s headquarters.

After a disguised messenger passed information between the Outram and Campbell, the preparations to meet with Campbell and the column were complete. The Residency was finally reached. The evacuation commenced on 19th November whilst John and the rest of the 78th defended and assisted. Campbell’s artillery bombarded the Kaisarbagh to misdirect the rebels’ attention, and after two days, Outram spiked the British guns and withdrew. Such was the precarious state of soldiers’ health, Havelock succumbed to a sudden bout of dysentery and sadly died on 24th November. There was no time to grieve, as both military and civilians moved to the Alambagh. On 27th November Campbell left Outram with 4000 troops, including John Statham, to defend it while Campbell, with 3000 troops and most of the civilians moved on to Cawnpore.

The first siege had lasted 87 days until the arrival of the relief column that included John. The second siege lasted a further 61 days. The Indian Mutiny Medal had three clasps relating to Lucknow:

- Defence of Lucknow awarded to the original defenders, 29 June to 22 November;

- Relief of Lucknow awarded to the relief force, November;

- Lucknow, awarded to troops in the final capture in November.

John Statham was awarded clasps 1 and 3. His records also reveal that he was awarded one year’s additional service ‘for Alambagh‘ under:

HORSE GUARDS GENERAL ORDER, NO. 810, JUNE 2, 1862.

Her Majesty having been graciously pleased to grant to the Officers, Non-commissioned Officers, and Soldiers who comprised the garrison of Lucknow, in 1857, the permission to reckon an additional year’s service towards pay and pension, and having been pleased to extend this boon to the force which entered that place under the late Sir Henry Havelock, in September of that year, is now further pleased to direct that the troops composing the detachment left by that Officer in the Alumbagh, on the 25th of September, together with those that subsequently entered it and remained there until the relief by Lord Clyde, on the 18th of November, 1857, shall also participate in the above-mentioned advantages. The additional year’s service in all such cases is allowed to reckon towards the qualifications for ‘medal and gratuity’. This grant is to be entered at once in the record of service of all those who are entitled to its advantages.

John moved regiment a second time. When the 78th were posted back to England, John volunteered for the 64th Foot which he joined in January 1859 but remained with them for just 28 days. No reason is given as to why, but he was then transferred to 75th Foot on 1st March 1859. The regiment was returned to Britain in 1860, however in the World-wide Army Census of 1861 John is stationed at Fort William in Calcutta with the 75th Foot. John served with them until his discharge in 1863.

Throughout his 22 years of service John remained a Private. We could speculate as to why this was, but it was not uncommon for soldiers to have a lengthy career without promotion. His record was excellent; he received five Good Conduct awards, never faced a Court Martial, nor did his name appear in any Regiment’s Defaulters’ book. John spent 17 years and 348 days serving abroad, and interestingly it is recorded that he spent 264 days at sea. In his forties, John was five feet and six inches tall, and described as having a fresh complexion, grey eyes, and light brown hair, but no marks or scars on his face or body (which considering his campaign record is remarkable). Another interesting note is that he had received all pay and allowances due him ‘except the whole of his share of Prize Money for Lucknow’.

He states that on discharge his intended place of residence will be Prees, near Whitchurch in Shropshire, which is 43 miles from Whittington, where he was born. It is possible he intended to go to family, however there is no indication that he went there. While awaiting his discharge in Devonport, John worked as a groom in Raglan Barracks. He met Phoebe Tyler at some point, and they were married on 1st October 1863. She was a spinster aged 33, and John lied about his age as it is recorded as 36 and not 41. Phoebe’s father was a Smith by profession and it was probably through his work as a groom that John met her.

By the time their son John Charles is born in February 1869, the family are living in Chelsea Barracks in London, where John is working as a Barrack Labourer. The Statham family were living in the cavalry barracks in Clewer at the time of the 1871 Census. He is a Labourer but also listed as an Army Pensioner.

By 1881 John Charles has left home. John and Phoebe have also moved on and are running the Oxford Blue in Old Windsor, listed in the census as Beer Keeper and Beer Keeper’s Wife. They took over the license at the Petty Session on 6th January 1872, from James Evans, a well-known Waterloo veteran. John and Phoebe were regular church-goers, no doubt instilled since his childhood, and were well-respected in the Old Windsor community. At the Berkshire Petty Sessions on Saturday 1st April 1882, John was appointed as one of three parish overseers, and is named before the other two. On Saturday 6th May, also at the Berkshire Petty Sessions John transfers the license of the Oxford Blue to Mr George Lisney, a gardener also from Old Windsor. It is likely that this is the time he becomes a Ballast Merchant.

By 1891, they have moved again and are living in Mills Cottages in Old Windsor, and in the census of that year John is listed as a Ballast Merchant. On Monday 18th April 1892, John was elected to the vestry Burial Board, and at the church vestry meeting held afterwards, he was one of six to be appointed a sidesman for the church. John and Phoebe are still in Old Windsor in 1901, living on Union Road with John listed as a Retired Stone Ballast Merchant. He met Lord Roberts two years later in 1903.

John died in 1907 and is believed to be buried in the cemetery of Old Windsor’s parish church. Phoebe was still living on Union Road by the time of the 1911 census. She died on 17th July 1915 and leaves her son John Charles £313.10s.6d in her will.

John Charles married Annie in 1892 and had two children, Alice born in 1893, and John (who was at least the fourth generation male to be called John) born in 1895. When their Grandfather died in 1907, they were aged 14 and 12 respectively. In 1901, John Charles is the publican at the Union Beerhouse in Old Windsor, but by 1911 he is a boat-builder and the family are living in Osbourne Cottages. Alice is 18 and at home with her mother on ‘Household Duties’, whilst 16 year old John is a Telegraph Messenger with the Post Office.

Carol Dixon-Smith

Sources

- England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567- 1970

- England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915

- Royal Hospital Chelsea Pensioner Soldier Service Records, 1760-1920

- Census Returns: 1841, 1871, 1881, 1891, 1901, 1911

- London, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917

- England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966

- David, Saul, The Indian Mutiny: 1857, Penguin, 2003

- Hibbert, Christopher, The Great Mutiny: India 1857, Penguin, 1980