Published in Windlesora 12 (1993)

© WLHG

The Penny Magazine was first published in 1832 by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge under the editorship of Charles Knight. As Knight had been brought up in Windsor and, with his father, started the Windsor and Eton Express it is not surprising to find that several of the articles in the magazine were about local affairs. In the issue dated 28th September 1833 Knight reports the opening of a “Public Library” for the use of the people of Windsor and Eton.

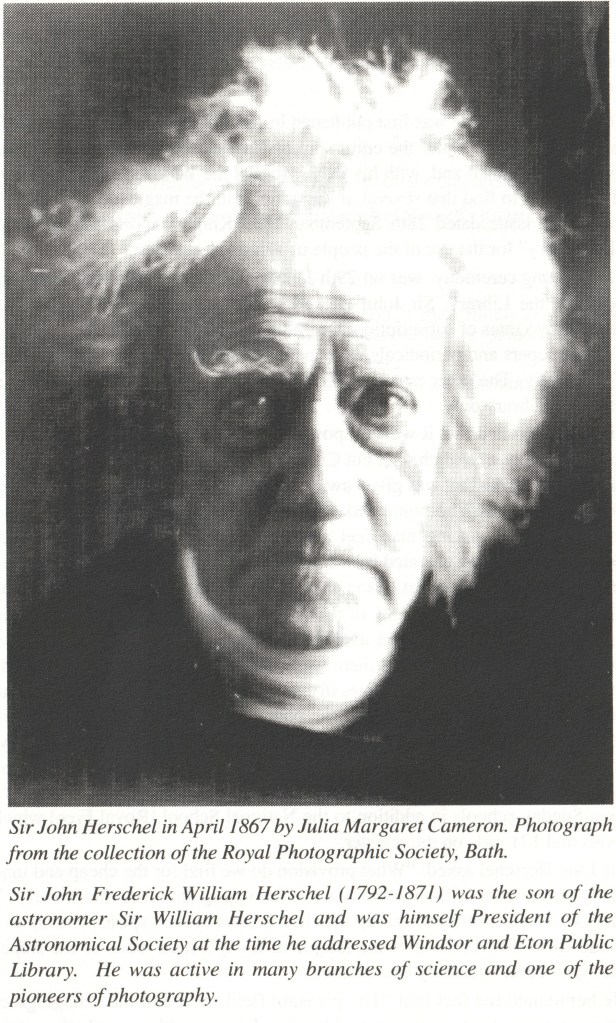

The opening ceremony was on 29th January and consisted of an address by the President of the Library, Sir John Herschel who started by explaining the rules. There were two rates of subscription. One admitted the subscriber to a reading room where newspapers and periodicals were available and allowed him to borrow books from the library. The other rate was for the “humbler classes” and allowed him the facility of the library only.

Sir John regretted that it was not possible for some people to be able to use the library completely free of charge, but Charles Knight was opposed to this idea as he thought that anything that was given away free was not prized by those who received it. “And besides this,” he continued, “the payment of even a penny a week to a library makes the working man feel as independent as the wealthier subscriber. While his mind is being elevated by the process of acquiring knowledge, it must not be degraded by the feeling that others are paying for the means of his improvement.”

There would have been plenty of the “humbler classes” able to read in Windsor as there had been free education available in the town for at least a hundred and twenty five years. In fact in 1818 there was a Select Committee on the Education of the Poor, which looked at the facilities in every town and the report of this committee included a short list of towns where “the poor have means of education”. Windsor was on this list which meant that the town council was not compelled to provide a school, the churches were doing enough. The Abstract of Educational Returns for 1833 gives details of nine infant schools, four daily schools, eight boarding schools and two Sunday schools in addition to the National School [Royal Free] which had 216 boys and 171 girls on the register.

Sir John Herschel asked: “What provision do we find for the cheap and innocent and daily amusement of the mass of the labouring population of this country? What sort of resources have they to call up the cheerfulness of their spirits, and chase away the cloud from their brow after the fatigue of a day’s hard work or the stupefying monotony of some sedentary occupation?”

He bemoaned the fact that “The pleasant field walk and the village green are becoming rarer and rarer every year. Music and dancing (the more’s the pity) have become so closely associated with ideas of riot and debauchery, among the less cultivated classes, that a taste for them for their own sake can hardly be said to exist.”

“The beer-shop and the public-house, it is true, are always open and always full, but it is not by those institutions that the cause of moral and intellectual culture is advanced. The truth is, that under the pressure of a continually condensing population, the habits of the city have crept into the village — the demands of agriculture have become sterner and more imperious; and while hardly a foot of ground is left uncultivated and unappropriated, there is positively not space left for many of the cheerful amusements of rural life.”

Sir John said that the hours when a man was not labouring should be used for amusement. Quoting the proverb “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” he said that a community of dull boys would be a society of “ignorant, headlong and ferocious men“. A man should not be urged into vice or crime, to acquire evil associates and brutal habits for the want of something better to do. Naturally he recommended reading. “It relieves his home of the dullness and sameness that drives him out to the ale-house, to his own ruin and his family’s. It transports him into a livelier and gayer and more diversified and interesting scene; and while he enjoys himself there, he may forget the evils of the present moment, fully as much as if he were ever so drunk, with the great advantage of finding himself the next day with his money in his pocket and without a headache. What he had read the previous day could accompany him to work so that he could enjoy it whilst absent from home and look forward with pleasure to his return.”

He then went on to discuss books that were written especially for the labouring classes in which the story is only a “cloak for the instruction intended to be conveyed – a sort of gilding of what they cannot well help fancying must be a pill when they see so much and such obvious pains taken to wrap it up.”

Sir John did not like these books “Try it on the other tack.” he recommends. “Furnish them liberally with books not written expressly for them as a class – but published for their betters, and those the best of their kind. You will soon find they have the same feelings to be interested by the varieties of fortune and incident – the same discernment to perceive the shades of character – the same relish for striking contrast of good and evil in moral conduct, and the same irresistable propensity to take the good side – the same perception of the sublime and beautiful in nature and art, when distinctly placed before them by the touches of a master.” He recommended novels by Cervantes and Richardson, Goldsmith, Edgeworth and Scott.

The address concluded with some suggestions of ways in which to read books, in the form of anecdotes and then Sir John said “If I were to pray for a taste which would stand me in stead under every variety of circumstances, and be a source of happiness and cheerfulness to me through life, and a shield against its ills. however things might go amiss, and the world frown upon me, it would be a taste for reading.”

“It civilizes the conduct of men, and suffers them not to remain barbarous.”

Pamela Marson