Two Jewels in Windsor’s Historic Treasury

Published in Windlesora 26 (2010)

© WLHG

‘A beautiful home is an inestimable treasure — and the harmony that is an integral part of beauty can only be found in things with a past, with a history, with secret vibrations that touch the finest fibres of our nature – Yvonne Bremond d’Ars.’

In Sheet Street in the heart of Windsor, directly opposite the junction with Victoria Street, stands a trio of eighteenth century buildings tinged with a portion of England’s history stretching back more than six hundred years before they were erected.

In 1795, Hadleigh House and its wings, to the north and south, were built as a single property for a local man, William Thomas, who became Mayor of Windsor in 1805. How the house acquired its name is lost in the haze of time.

William Thomas was an apothecary and subsequently a surgeon. A suggestion that he was one of Queen Anne’s doctors is fanciful – he would have been very old as Queen Anne died in 1714, eighty years before the house was built.

Following William Thomas, the house was occupied by another doctor named John O’Reilly, Surgeon Apothecary to the households of George IV and William IV. In 1819 it is recorded that he attended the Duke of York, who fell and broke his arm when one of his spurs caught in the loop of his pantaloons. George IV thought little of O’Reilly’s skills, saying that he was ‘the damndest liar in the world’, although His Majesty was said to have enjoyed his gossipy company.

It was O’Reilly who, on 17 September 1801, was summoned to St Leonard’s Dale, where General Harcourt had fallen from his horse, but by the time O’Reilly arrived the General had already expired.

An episode with a more felicitous ending concerned a chimney sweep’s boy who became stuck in one of the chimneys. To encourage him to move, his master lit the fire below, whereupon the terrified child climbed onto the roof, only to fall into the forecourt. Amazingly, however, he arose uninjured.

The next occupier was yet another doctor, one Henry Brown, a partner of John O’Reilly, who had died in 1833. Brown became a favourite of Queen Victoria. It was Brown who delivered the Duke of Clarence, first child of the Prince and Princess of Wales. This was an unexpectedly premature birth and in the absence of a layette, the baby was wrapped in Lady Mansfield’s red flannel petticoat.

The North Wing was used by Henry Brown as his surgery. He died in 1868. His family left Windsor but retained Hadleigh House, which was let to a series of tenants. Thus ended for the time being the medical connection.

The defining moment for the integrity of the property as a single unit came in 1914 when the freehold was purchased by Mr Arthur Francis Gresham Leveson-Gower. Leveson-Gower was an aristocrat and a diplomat with a peripatetic career. He and his wife, Caroline, had four children – William born in Brazil, Emily in Austria, Victor in Germany and Osbert in Switzerland. Leveson-Gower had diplomacy in his blood being of the family which produced the first Lord Granville, a personal friend of the Younger Pitt, by whom he was sent in 1804 to negotiate an alliance with the Russia of the Tzar Alexander I.

It was a grandson of Granville – the fourth Earl – who married Lady Rose Bowes-Lyon, elder sister of the Queen Mother, whose younger daughter, Mary, married Samuel Clayton, a brother of Doctor John Clayton, a respected medical practitioner in Eton. Lady Mary lives at Cumberland Lodge in Windsor Great Park to the present day.

It was presumably because of Arthur’s prolonged absences that he decided to separate Hadleigh House from its northern adjunct. The main house was let to Sir George and Lady Mary Crichton, whilst he occupied the northern wing, which he named Clifford Lodge.

The origin of the Lodge’s name is not so great an enigma as is that of Hadleigh House. Arthur Leveson-Gower rejoiced in a remarkable ancestry. A kinsman of the Dukes of Sutherland and of the Earls Granville, he was able to trace his lineage back to Rollo a Viking Chieftain, who in the tenth century became first Duke of Normandy and was an ancestor of William the Conquerer. For my purposes, however my story begins with Richard Fitz-Ponz, whose son Walter in the twelfth century acquired, through Margaret, his wife, Clifford Castle, about four miles north of Hay on Wye, from which edifice he took his surname.

Walter’s daughter, Rosamond de Clifford, bears a name which flashes from the pages of England’s history. As the beautiful Fair Rosamond she became mistress to Henry II. Reputedly murdered by the Queen, she was buried at Godstone Nunnery on the Thames near Oxford.

Walter’s great grandson, Roger de Clifford, was appointed Justice of all the Kings’ Forests, south of Trent and was granted the Lordship of Old Kingsbury in Warwickshire. He died in 1255 and was succeeded in his turn by his grandson, Robert de Clifford, who was a prominent soldier in the reigns of Edward I and Edward II. He was created the first Baron Clifford in 1299. He was killed at the Battle of Bannockburn on 24 June 1314.

The Cliffords of that era were a pretty sanguinary lot. Robert’s son Roger, the second Baron, was possibly executed as a rebel at York in 1322, but more probably was reprieved after suffering a severe head wound at the Battle of Boroughbridge and lived on for another five years.

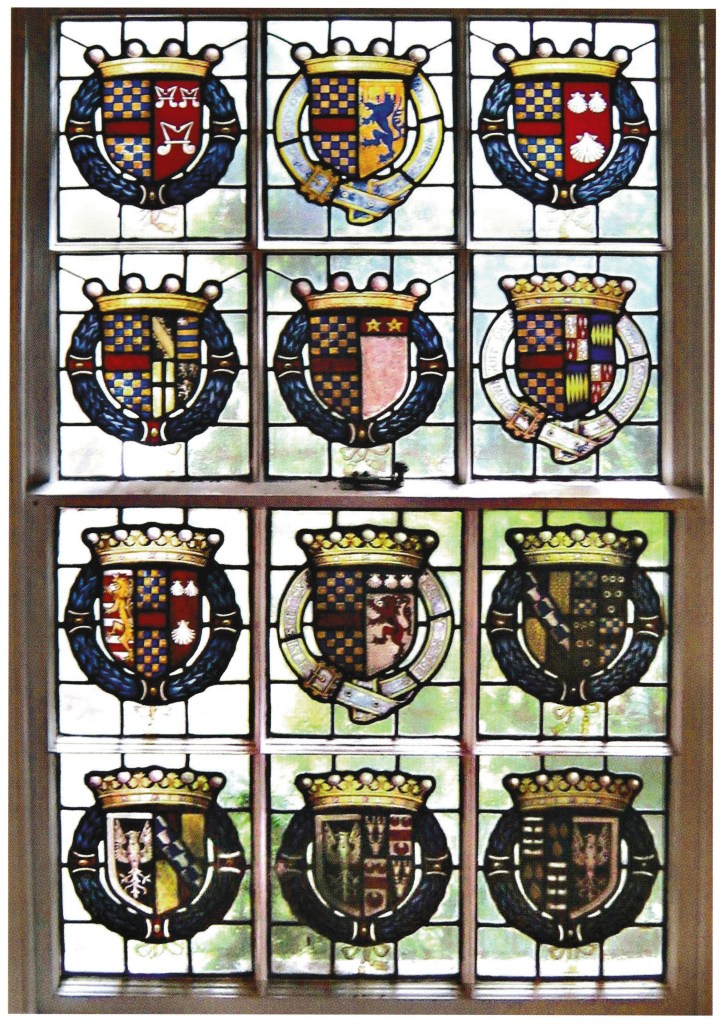

Fig. 1 The window at the side of Clifford Lodge.

The next milestone leads directly to Clifford Lodge, where, above the turn in the stairs, may be seen a splendid window containing twelve panes of stained glass, each one displaying a magnificent coat of arms. These blazons depict the arms of twelve generations of the Clifford family, impaled with those of their respective spouses (fig.1). The first shield (top left) shows the arms of Thomas, Sixth Baron Clifford, who was born in 1393, impaled with those of his wife, Elizabeth, daughter of Lord Roos of Hamlake. The Clifford Arms (Chequy, or and azure, a fesse gules) appear in the first nine lights ofthe window. Three coats of arms are encircled by the ribbon of the Garter, the first being that of Thomas’s son, John, the Seventh Baron, espoused to Elizabeth Percy, daughter of the renowned Harry Hotspur, who fell at the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403. John himself was killed at the Siege of Meaux in 1421. Henry, the eleventh Baron, was raised to the Earldom of Cumberland (sixth light) and, like his grandson, George, the thirteenth Baron and third Earl (eighth light) was appointed a Knight of the Garter. It will be noticed that with the creation of the Earldom, the Baron’s coronets of the Cliffords were exchanged for the Earl’s coronets of Cumberland. George, the third Earl, was married to Margaret, daughter of the Earl of Bedford, whose arms appear impaled with his, the whole surrounded by the Garter (light eight and fig.2).

Figure 2.

Henry the twelfth Baron and second Earl, was married twice, hence the Clifford Arms being set between those of his first and second wives (seventh light). The former, Eleanor, was the daughter of Charles Brandon, first Duke of Suffolk, KG, and Mary, the second daughter of Henry VII, and it was on account of this union that their granddaughter – the Nine Day Queen, Lady Jane Grey – made her bid for the throne, which ended when she went to the block in the Tower of London in 1554. Charles Brandon, a close friend of Henry VIII, with whom he was present at the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520, is buried in the South Quire aisle of St George’s Chapel.

Reverting to the savagery of the Wars of the Roses, Thomas, the eighth Baron (a Lancastrian) (vide the third light) was killed at the first battle of that internecine struggle at St Albans in 1454. His son, John, the ninth Baron (the fourth light), known as The Butcher, avenged his father in 1460 by stabbing to death the Earl of Rutland, son of the Duke of York, reputedly on Wakefield Bridge, crying as he did so ‘By God’s blood thy father slew mine and so will I do thee and all thy kin’. Rutland’s poignant plea for mercy in all its pathos appears in Shakespeare’s King Henry VI.

‘Sweet Clifford, hear me speak before I die.

l am too mean a subject for thy wrath:

Be thou revenged on men and let me live’

Clifford’s vengeance was not to be denied: ‘Thy father slew my father; therefore, die’.

The Butcher was himself shot dead the following year with an arrow through the neck in the twelve hour Battle of Towton, which is said to have been the bloodiest battle ever fought on English soil.

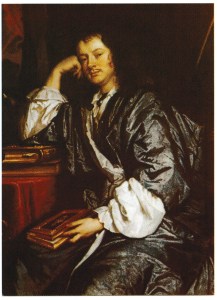

From John’s younger brother, Sir Lewis de Clifford, KG, was descended Thomas, first Baron Clifford of Chudleigh in Devon, whose services were used by Charles II, in company with the King’s sister, Minette and others, to secure the Secret Treaty of Dover with France in 1670. Clifford was described by John Evelyn as ‘a valiant, uncorrupt gentleman, ambitious, not covetous, generous, passionate, a most constant, sincere friend’ (fig.3).

Figure 3.

The ninth light contains the arms of The Lady Anne, de juré, Baroness Clifford, and those of her husband, Richard the third earl of Dorset. Their great grandson, John, was created the first earl of Gower. His arms, impaled with those of Lady Mary Tufton, his wife, appear in the twelfth light (fig.4).

Figure 4.

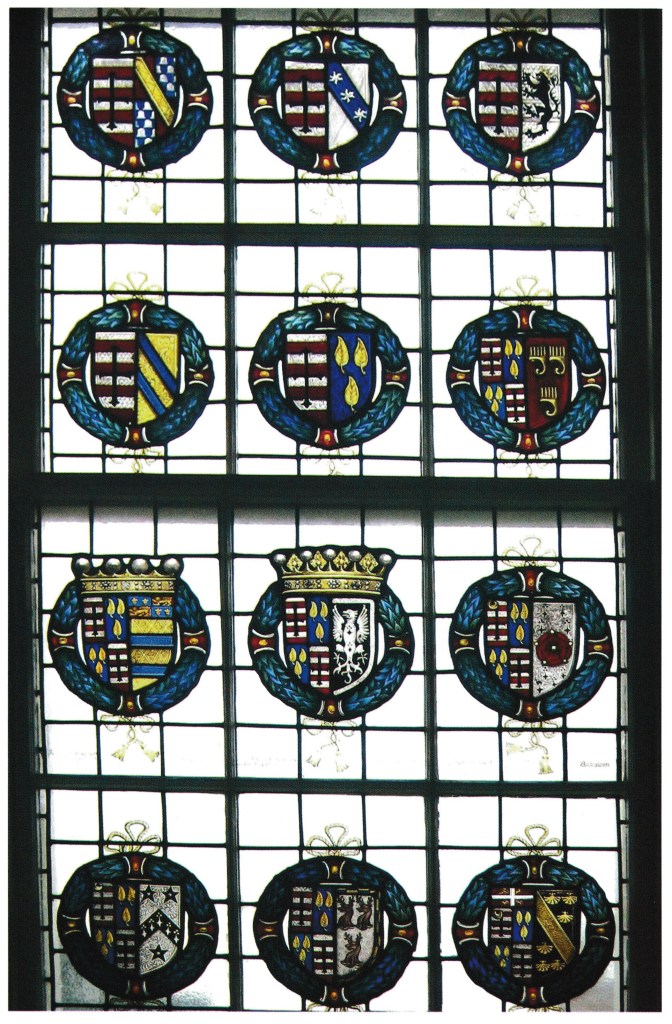

Leveson-Gower continued his armorial testimony to his ancestors with a second window, also of twelve lights, set above the staircase in Hadleigh House (fig.5). The first seven lights of the Hadleigh House window depict the arms of Gower, culminating with those of John, first Baron Gower who married in 1692 a daughter of the Duke of Rutland, with whose arms those of Gower are impaled.

Fig. 5 The Window in Hadleigh House

The eighth light (of John, first Earl Gower) is the only repeat in the whole twenty four light sequence, save that the inscription notes that the Earl also held the Viscountcy of Trentham. Thereafter, the absence of coronets in the remaining lights indicates the infusion of younger sons.

The final light, unsurprisingly, displays the arms of Arthur Leveson-Gower himself, impaled with those of Caroline Foljambe, whom he married on 4 August 1881. (fig.6) The arms of Arthur’s parents, William Leveson-Gower and Emily Doyle, appear in the preceding (eleventh) light. Arthur was the second son of his parents, denoted by the mark of cadency (a crescent) in the shield. It will be noted also that there is a ‘chief’ at the top of Arthur’s shield, presumably denoting some high point in his diplomatic career.

Figure 6.

It is recorded that whilst living in Clifford Lodge, Arthur kept the key of the main house and would watch to see when the tenants went out. He would then go all over the house to see if they were keeping it properly. One day they returned unexpectedly and he hid in the attic but was eventually discovered and, to quote, ‘there was a terrific row’.

Leveson-Gower lived in Clifford Lodge until he died in 1922, when the property was finally split. The main house was purchased by Mr C H Blakiston, a Master at Eton College, who subsequently became Headmaster of Lancing.

In the meantime, Clifford Lodge came into the possession of Miss Tugini d’Ablaing. Miss Tugini was half Italian and half Dutch, a little elderly lady who, bent almost double and dressed in black, could often be seen walking around Windsor.

In due course, a tenancy was taken of the main house by Mr Angus Macnaghten, whose family occupied it for twenty five years. His mother, Mrs Hazel Macnaghten, lived there virtually on her own during the War. She wrote regularly to her son who was away on active service. Angus Macnaghten kept all her letters and in 1985 published a selection crammed with local gossip, often mischievous about many Windsorians, both prominent and otherwise of the day. One of these was Miss Tugini d’ Ablaing.

To bring Hadleigh House and Clifford Lodge up to date, Angus Macnaghten eventually left Hadleigh House, which with the Annexe was purchased by a local solicitor, Philip Willmett, who carried on his solicitor’s practice in the Annexe where the firm still practices. Willmett sold Hadleigh House itself to the Windsor surgeon, David Bain, on whose death the house was sold to Mr and Mrs Stuart Eastwood.

As for Clifford Lodge, on Miss Tuginti’s death, it was bought by the Windsor Constitutional Club, founded in 1886, upon vacating the Club’s previous premises in Windsor High Street.

So concluding these few morsels of Windsor’s rich history and of the colourful Clifford ancestry hidden away behind the modest yellow door of Clifford Lodge and the rather more lordly portico of Hadleigh House, the words of the Duke of St Bungay in Trollope’s Phineas Redux come to mind ‘I do think that the England which we know could not be the England that she is but for the maintenance of a high-minded, proud and self-denying nobility’.

John Handcock

Sources

Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage

de Mare: Time on the Thames

Fellowes: The Knights of the Garter

Hague. The Younger Pitt

Macnaghten: Windsor & Eton in Georgian Times, Windsor & Eton in Victorian Times, Windsor in the war 1939-45.

Poole: Great British Families

Ross: The Wars of the Roses

Vickers: Elizabeth, the Queen Mother

Acknowledgements

Especial gratitude is extended to Capt. The Rt. Hon. The Lord Clifford of Chudleigh, DL for advice and photographs; to Mr DJH Clifford, Chairman of the Clifford Association and Mr DAR Waterton-Anderson for advice; to Mr and Mrs Stuart Eastwood, for their welcome to Hadleigh House and permission to photograph; and to Windsor Constitutional Club for a like permission.