Published in Windlesora 21 (2005)

© WLHG

‘Windsor is the dirtiest and most unsanitary of all the towns in the South of England.’ This was the opinion given in the Chadwick Report of 1842 and there was much to confirm this opinion.

Windsor had several brooks running through it, starting as springs rising from beautiful pure artesian wells on St. Leonard’s Hill, probably the purest in the whole of Berkshire. Here however the purity stopped. Only two streams are mentioned for the purpose of this article, the Bourne ditch and the Black ditch.

The Bourne ditch ran through Spital, Frances Road, Kings Road, via Brook Street, and across the Park and into the river, collecting sewage outflows from those who already had water closets and night soil from those who had no gardens, the effluent from the Cavalry Barracks and other ‘noisesome’ filth. High rainfall on St Leonard’s Hill often caused flooding in Bourne Avenue.

At this time, it was thought that it was the ‘miasma’ (atmosphere) which caused disease and when Windsor fell victim to the cholera that was spreading from Europe to England during 1848/49, the Bourne ditch was blamed. The national epidemic did in fact frighten the Government into passing the Public Health Act in 1848 which only went a little way towards solving the nation’s sanitation problems.

Windsor was however stung into cleaning up its streets and in 1851/52 the main sewer was laid through the town, passing across the Park to deliver untreated sewage into the river opposite Datchet. The outflow from towns upstream, Windsor, Reading with its abattoir and High Wycombe with outflows from its many mills polluting the River Wye, added unspeakable noxious solids to the collection and during the long hot summer of 1858 caused the notorious Great Stink which even affected Members of Parliament, resulting in hurried legislation.

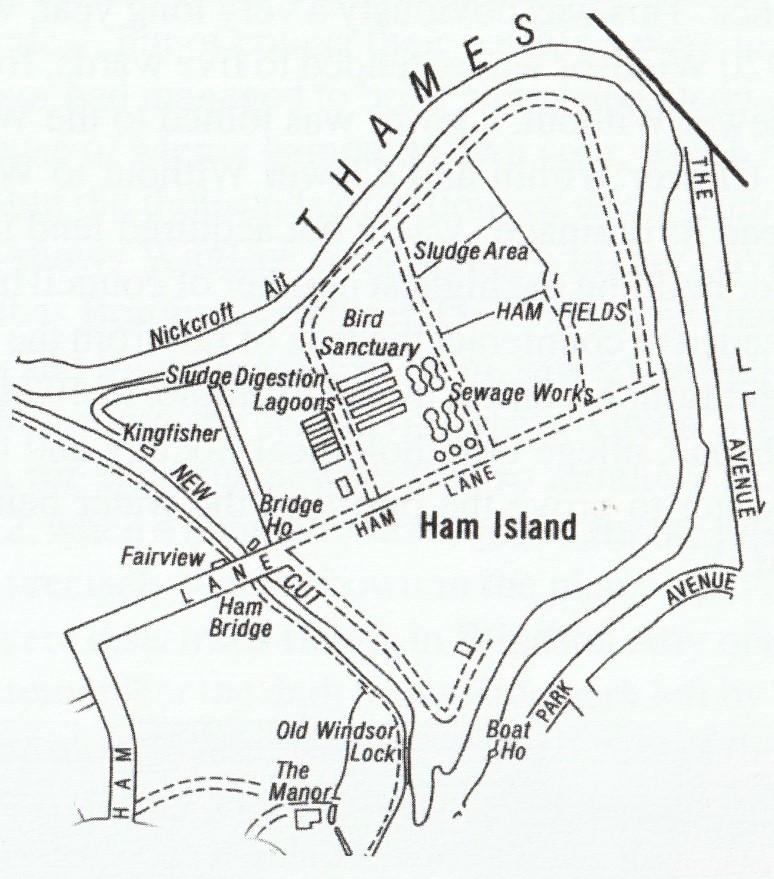

In 1872 Windsor was sued by the Thames Conservancy Board (1857) under the Sewers Utilisation Act (1865). There were few such convictions and manufacturers were always able to prove that their business and livelihood would suffer in some way and continued their polluting unabated, pouring chemicals into Britain’s rivers. Manufacturing interests were more important than public health. Windsor had no large industry with the result that in 1875, with the sanction of the Local Government Board and Windsor Sanitary Authority, £47,531 was borrowed from a public fund set up for this purpose to purchase land at Ham Island, in the parish of Old Windsor, enlarge the sewerage system and build treatment beds. Windsor was a poor borough and rates were set upon land values and as Windsor had no land and rate increases were vigorously opposed, this was not completely repaid by 1895.

The Windsor and Eton Express reported in 1875 that ‘The main sewer commences near the town bridge and passes westward and afterwards southward, skirting the foot of sloping ground and receiving tributary branches on either side and is the carried eastward across Windsor park to an irrigation farm not far from the riverside flushing points’. Water was needed to flush the sewage pipes. This was taken from the river at Bier Lane and sulphate of iron added. At the treatment plant at Ham Island the sewage ran into settling tanks, the liquid was run onto the irrigation area and the sludge was pumped onto drying beds. Between 1875 and 1889 this farm was extended and in 1890 more land was acquired and another £59,000 was borrowed.

Windsor still had no clean water supply. There had been a water wheel on Tangier Island since 1666 taking water from the relatively clean Thames. With the increase in town populations because of the national change from an agrarian to an industrial economy, and the belief between the 1780s and 1830s that the waterways would purify, the Thames became just another open sewer. Sludge and ashes were raising river and stream levels and turning the sandy banks into slimy mud. Dr. John Snow showed in 1854 that cholera was spread through polluted water and since Windsor was dependent on the river and wells, cholera was an ever-present threat. Enteric fever was endemic. However, reform was slow to come. This is shown by the following dates:

20th August 1883 The Windsor and Eton Waterworks act £85,000 was agreed for building by the Waterworks and Gas Companies.

7th January 1888 Arbitration over the cost of purchase of site.

October 1888 Agreement of the site of the waterworks at Tangier Island. 1892 Dedworth received its first piped drinking water supply to the Church, The Limes and The Willows but Clewer still resisted paying for sewerage.

Clewer had several brooks which had become foul ditches and a report in the Windsor and Eton Express pinpoints the worst sections as ‘Clewer Green around by The Prince Albert, the ditch by Lover’s Walk, Clewer Institution… long line of ditch at back of Dedworth… close to the Police Station, opposite Parochial Hall, Clewer New Town and some parts of Clewer itself’. That part known as the Black ditch, for reasons which need no explanation, ran through Clewer, under the bowling green entering the river near Wicks Café by Windsor Bridge. A newspaper editorial contained the remark: ‘It does not require the possession of extremely sensitive olfactory organs to discover the nuisances that exist in Clewer.’

Windsor suggested that Clewer join onto the Windsor system at the minimum rate of 8d.

The problem was that Windsor Borough was itself a Sanitary Authority but Clewer was controlled by the Board of Guardians, in other words the Vestries consisting of the powerful local landowners, many of whom had their own drainage systems. They considered that Clewer did not need a system and would not therefore be ‘saddled with high rates’, but of course their outflows were into the Black ditch.

By 1890 Windsor had managed to bring Spital and Dedworth under its jurisdiction. In 1892 the House of Mercy gained its own spur, which ran down the south side of Clarence Road, but the thousands of gallons of water from its laundry caused problems and a memo shows Windsor considering a higher payment. In the early days of his appointment as Borough Engineer, Gordon Cullingham had to check the House of Mercy sewers and following one of them, saw some lights ahead and found himself looking straight up into the toilets of Clewer Green School. John Rowe’s original ordinance plan for Windsor Sewers was so minutely exact that it was still being referred to in 1972, when a manhole was required for the pipe in lower Peascod Street. At 20’ 6” it was precisely where shown in the plan.

In 1894 there were disastrous floods in Windsor. Any one who experienced the floods of 1947 may remember the dark brown tidemark left by the receding water on the walls of the houses along Arthur Road up to the height of the windowsills. But in 1894, added to those waters were the contents of Clewer’s foul ditches, open sewers, dung heaps both from Clewer and towns upstream, offal and blood from the abattoir, dead animals and chemicals. A small measure of the sanitary conditions of Clewer can be realised. Clewer was harangued for delay over drainage, by the Surveyor Mr Menzies. It was said of Mr Murray-Brown of the Local Government Board, ‘Cholera is hanging over the country and Clewer was one of the places where he would shudder to hear of cholera making its appearance’.

In 1895 Clewer suggested siting its own drainage system and irrigation farm between Clewer Park and Surly Hall Hotel, a low-lying area by the river. Among the families living close to the river consumption (TB) was ever-present. They had the highest incidence of whooping cough and scarlet fever and during the smallpox epidemic in 1893, the greatest number of cases. It was the latter which prompted Windsor into greater efforts to bring Clewer into its sewerage system. In 1895 the Mr Menzies, the County Surveyor stated angrily that, ‘If Clewer does not find a solution to its drainage problem the board (Local Government Board) would find it necessary to do the work and send Clewer the bill, which would be more expensive than the suggested rate increase to join the Windsor system.’ However, ‘local pride, vested interests and ideological barriers obstructed advances down many obvious and logical paths…..progress contested and achieved in the teeth of bitter opposition.’ This was not said specifically of Clewer but was a general situation throughout the country. ‘If the Clewer Highway Board (which was a laughing stock) is an example of future parish and village councils then the parishes are to be pitied.’

In 1904 there was a general enquiry over Clewer’s drainage problem which was reported at length and lasted over several days. Windsor was applying to bring Clewer into the Borough as the only solution. This was shelved for another year due to Clewer’s truculence. This was obviously a very long year, which was extended by WW1. At last in 1920 Windsor was extended to five wards, from the three created in 1886, to include Clewer Without. Clewer was joined to the Windsor System.

By adding Clewer Within and Clewer Without to Windsor Borough it not only needed to extend its drainage system but acquired land for expansion and after WW2 was known for building the highest number of council houses at speed. Pumping stations were needed to counteract the lack of fall from the low-lying districts and Ham Island treatment farm became a model example. In 1934 it became a bird sanctuary overseen by Eton College Ornithological Society and the many visitors were offered a glass of water to prove the purity of the water being discharged into the river after treatment.

The original pump house at Ham Island Treatment Farm, now used as offices. (Photograph courtesy of Thames Water)

Windsor lost its Water Authority status in 1965 and Thames Water gained authority for sewerage, sewage disposal and water supply in 1974. During these years a surface water system was added with an outflow into the Bourne ditch – there would not be a similar problem to that experienced by the London sewers during the heavy rains in August 2004.

In 1985 salmon were seen at London Bridge, the first for over 150 years and salmon ladders are now built into all weirs. A Thames river trip is one of the most pleasant ways to spend a day and houses along its banks are the most expensive and sought after. It took Windsor nearly two centuries to raise itself from the dirtiest town to one of the top tourist attractions.

Valerie Batt-Rawden

Primary Sources

Annual Report, Clewer House of Mercy 1892/93 Berkshire Record Office

Clewer Parish Magazines 1886-1897 BRO

Windsor & Eton Express 19th c. to 1907 Slough Public Library

New Windsor Council Minutes 19th c BRO.

Board of Guardians Reports 19th c. Health and Drainage Committee Minutes 19th c.BRO

Inspector of Nuisances reports 19th c. Reports of Poor Law Commissioners, Poor Law

Board, Local Government Board (Berkshire) 19th c. BRO

Kellys Directory 1935

Roy Fuller, Senior Assistant Borough Engineer Windsor (1962-1974)

Notes made by Gordon Cullingham, Borough Engineer Windsor until 1974