Destruction of the Theatre Royal

Published in Windlesora 26 (2010)

© WLHG

2010 will mark the centenary of the current Theatre Royal. Its predecessor, opening in 1814, had lasted a little less than a hundred years when it was destroyed by fire.

The play performed on Monday 17 February 1908 was an exciting one which was called The Scarlet Clue and had a scene where a little girl was rescued trom the roof garden of a burning hotel. Three flaming torches were used to create a dramatic effect, but they were carefully extinguished and when the mother of the girl in the play, watching from the stalls, came round back-stage to say that she could smell burning nothing untoward was discovered, Actors and audience went home, the theatre lights were turned off, and the building locked up.

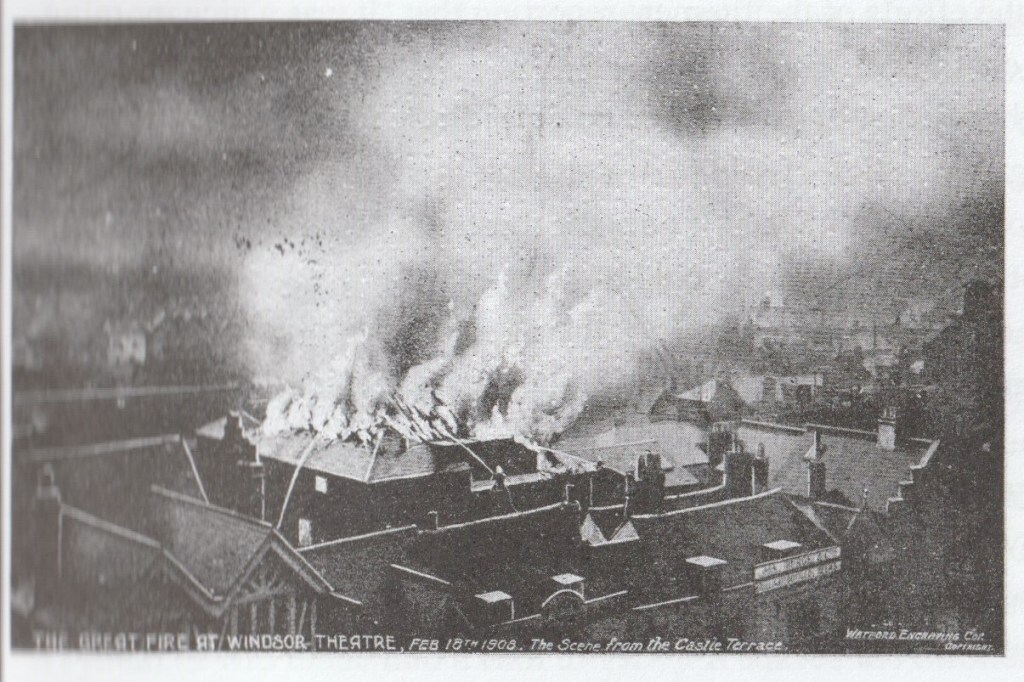

It was a quiet moonlit night until sometime after 4am when a sentry on duly on the Castle terrace spotted flames and shouted ‘Fire!’ – but there was no one to hear, the gates were locked and he could not get off the terrace. When the night-watchman at the Corporation Waterworks on Tangier Island noticed a glare in the sky; he contacted the police and ensured that the mains were supplied with a good pressure of water through accelerated working of the turbines. But the first call to the Windsor Fire Brigade was made by Thomas Butler working at the South Western Railway station, who saw flames coming through the theatre roof. Soon people living around were woken by crackling noises and hurried out to witness the conflagration.

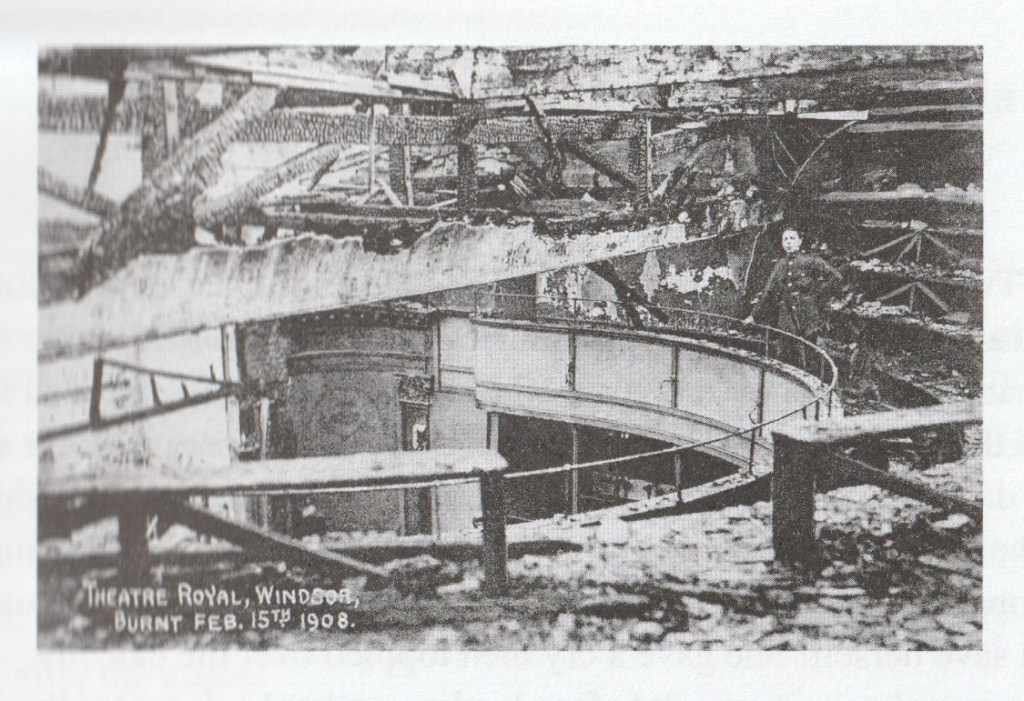

Captain Henry Hall, the Chief Officer of the Windsor Fire Brigade who lived in Thames Street, at once got in touch with his other officers. They arrived swiftly, bringing with them equipment which was variously lodged in Church Street, Victoria Street and Alma Road sub-stations, and they got to work, pouring vast quantities of water onto the fire from the hydrants and the river. They were joined by the Eton Fire Brigade with its steam fire-engine, and then the Windsor Castle Fire Brigade; within an hour the fire was under control. Indeed the Windsor Express account, with its sub-heading ‘Splendid work by the Fire Brigades’, seemed more impressed by the effectiveness of the fire-fighters than with the tragedy of the loss of the theatre. In the morning the extent of the devastation could be seen: the back-stage area had been totally burnt out, though because of the asbestos safety curtain the auditorium was less affected, damaged mainly by the vast quantities of water poured onto it.

A Windsor Express ‘eye-witness’, called from his bed at five in the morning to see the blaze, was not too concerned. He had enjoyed the spectacle and the efforts of the firemen, reporting that ‘It was a nice morning for a fire’. He continued:

‘I might say that I never looked on at [a] fire with a more comfortable feeling. It was time, I said to myself, that this antiquated old building was done away with, and if only the theatrical company performing are not affected no tears would be shed.’

But of course, even if no lives were lost, there was human price to pay. Grace Warner, performing in the theatre with a troupe of 14 including two children, learnt that

‘all my stage property, scenery, music, manuscripts, &c, are destroyed. The accumulation of years are gone, and cannot well be replaced. I have lost nearly £300 worth, and my manager, Mr. George Gordon, has lost quite £80 worth of clothes, jewellery, &c.’

Gone forever was the well-loved theatre curtain painted with a scene of the Long Walk looking towards the Castle, with deer in the foreground. Gone too were all the musical instruments, including the piano. Additionally there was damage to adjoining shops, the grocer’s and wine and stock merchant’s at 30 Thames Street, a confectioner’s and a fruit and flower seller. The action of the Fire Brigade had prevented the fire spreading, but there was considerable water damage, and Mrs Hand, the fruiterer and flower seller, was not insured.

The theatre was owned by Sir William Shipley and Major Reginald Shipley, but had been leased to an energetic northerner, Jasper Redfern, who also ran theatres in Sheffield and Manchester. Under his direction the Windsor theatre had recently thrived, with visiting companies and the exciting introduction of cinematograph programmes.* After the fire the theatre would be dark for many months to come but the Shipleys were determined that it would open again, and nearly two years later a ‘splendid new Theatre and Opera House’ on the same site was ready for business. The architect was Frank Verity ARIBA, whose design was notable for its ornamental restraint, with none of the gods, goddesses and cupids found disporting themselves over the walls and ceilings as in many theatres. Of course, this time fire-resisting materials were used throughout.

The new theatre was larger than the old one, adjoining property having been bought to create a more generously-proportioned building; there was seating for approximately 850, with a good view of the stage ensured for all, It was also a storey higher, which enabled scenery to be raised above the stage and a single fire-curtain to be used (the old safety-curtain which had limited the spread of the fire had had to be in two pieces, half coming up, half down). The down-side to this was that the higher roof-line now cuts off some of the famous view of the Castle from the Goswells.

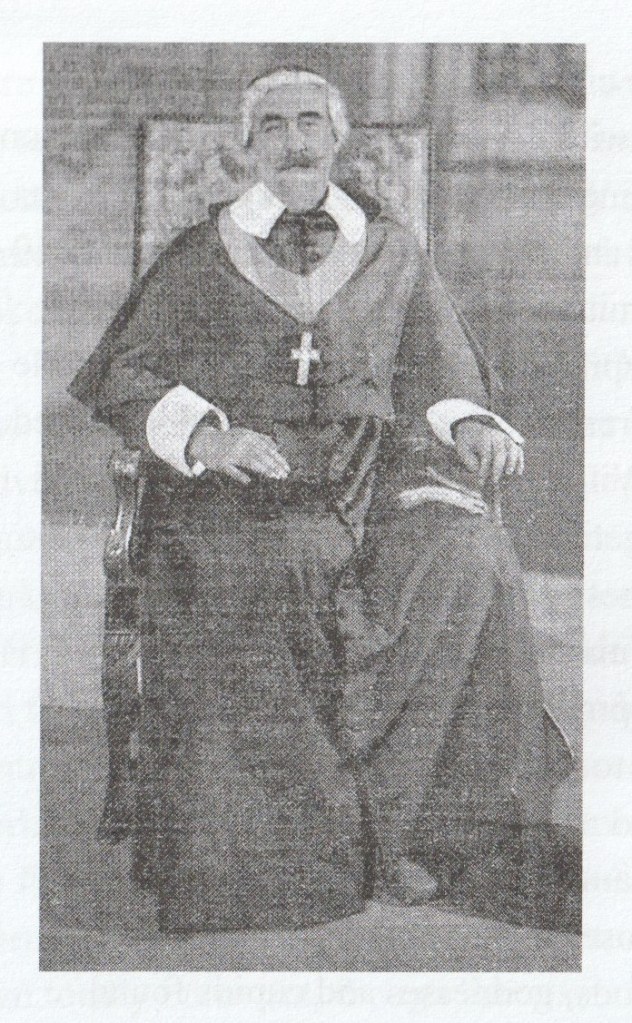

The honour of re-opening the theatre, on Tuesday 13 December 1910, went to the Windsor Strollers, a prestigious amateur group formed in 1860 who had performed many times on the old stage; a founder member, the splendidly-named Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, then in his eighties, had a walk-on part. To a packed house they presented Under the Red Robe, a romantic drama of the seventeenth century adapted from a novel by Stanley J. Weyman (it was made into a film in 1937). It starred the Strollers’ President, Captain AF Liddell, as Cardinal Richelieu, the wily chief minister of Louis XIII. Anxious to avert a Huguenot plot he gets his chance when the swashbuckling Gil de Berault fights a duel, which was punishable by death: the Cardinal will spare his life if he will act as a double-agent, infiltrating the insurrectionists to bring about their downfall. De Berault agrees, only to fall in love with their leader’s sister …

The President of the Windsor Strollers (Captain AF Liddell) as Cardinal Richelieu in ‘Under the Red Robe’.

But all ends happily with the Express reporting that ‘the eyes of many in the audience were tear-dimmed’ as de Berault (played by Mr Alan MacKinnon) leads the heroine (Mrs Charles Crutchley) ‘into a brighter day’. As well as pleasure in the play much admiration was expressed for the new building — apart from one or two who complained of draughts!

Next day the theatre had its first royal visitor in Princess Christian; all the profits were to go to King Edward VII Hospital in whose foundation she had been a prime mover. Then after the first two weeks there began a run of professional productions; on Boxing Day The Fatal Wedding, a musical of New York life and love brought from the Princess’s Theatre was staged (it was made into a movie -though a silent one — in 1911). To begin the New Year there was another musical, from Daly’s Theatre in London: The Cingalee, with songs by Lionel Monckton, a romantic tale set among the tea-planters of what was then Ceylon. Seats in the theatre cost from 6 old pence to 5 shillings (25p), with boxes from one to three guineas, and to make it easier for patrons from outside Windsor a bus was run to Slough, and special trains were put on to Staines on a Wednesday evening. Tickets were much in demand and the Theatre Royal was set for a bright and long-lasting future.

Hester Davenport

References

Windsor Express for 22, 29 February 1908, 10, 17, 31 December 1910

http.//www.victorian-cinema.net/redfern.htm

Notes:

(1) Redfern was an optician in Sheffield who developed an interest in moving pictures and began by filming football matches and other local events. He created short feature films such as A Monkey Steals some Ice-Cream (1904), Stars of the Cricket World and Uncle Podger’s Mishaps (1905), and he formed a business called the ‘World Renowned Animated Pictures and

refined Vaudeville Entertainments’. He also had an interest in X-rays and ultimately turned from cinema to devote himself at a hospital in Manchester for medical research and the treatment of cancers. Sadly, the damaging effect of X Rays were not fully understood then and Redfern died of radiation poisoning.