Published in Windlesora 24 (2008)

© WLHG

In the spring of 2007 crowds flocked to see the exhibition ‘Canaletto in England’ at Dulwich Picture Gallery. Giovanni Antonio Canal (1697-1768), called Canaletto, was a Venetian artist best known for landscapes of his native city, but from 1746-55, when the War of the Austrian Succession restricted the flow of well-heeled tourists to Italy, he sought the commercial opportunities of London, The series of large paintings he produced, brought together in the Dulwich exhibition, provide an extraordinary documentary of life in the capital in the mid-eighteenth century, Not only are London’s river banks, open spaces, grand houses and cathedrals represented in detail, but the scenes are brightly peopled: women in the ballooning skirts of the day promenade, men of fashion strut or chat, soldiers parade, servants attend to their chores, children play, boatmen ply their trade, dogs sniff and scratch.

On a few occasions, Canaletto moved outside London for a commission, as when he painted Windsor Castle (33 x 54 ins), which was also on view at Dulwich. Like the London landscapes, Windsor Castle combines the permanent and the momentary, the static precision of architectural detail with a kaleidoscope of human activity. The golden glow of a summer evening falls on the usually-shadowed northern walls of the Castle, while Majesty, in the form of the Royal Standard flying from the old Round Tower, presides over a rural idyll below, where young and old, peasants and the well-to-do mingle together by the quiet waters of a channel of the Thames. The painting seems to comment on the stability of the English social order.

Windsor Castle normally hangs in Alnwick Castle in Northumberland, with a companion piece, Syon House. Both paintings at one time belonged to Sir Hugh Smithson (subsequently created 1st Duke of Northumberland), a political grandee and artistic connoisseur who commissioned several paintings from Canaletto. But it was argued in the Dulwich catalogue by Charles Beddington, the curator of the exhibition, that these two pictures were ordered, probably with Smithson’s encouragement, by his father-in-law, Algernon Seymour, Earl of Hertford.(1) He owned Percy Lodge at Richings Park at Iver (later burned down), so Windsor Castle would have been more or less on his doorstep.(2)

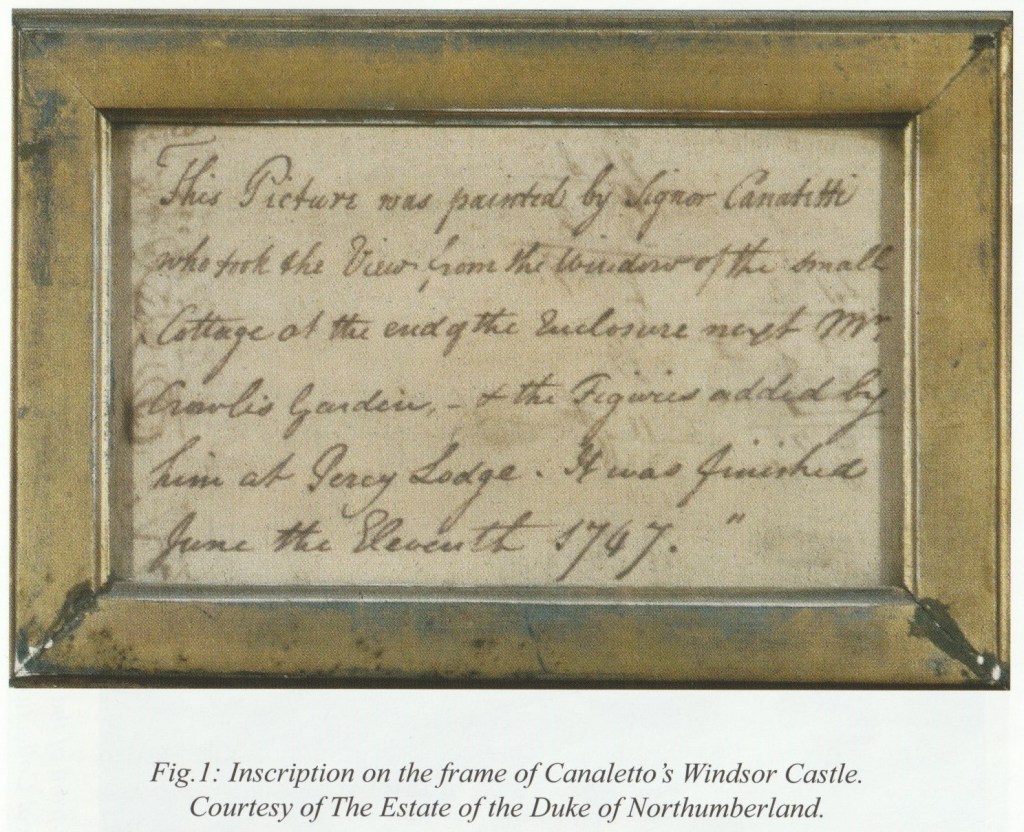

This theory accords with the most intriguing and unusual aspect of the picture, the hand-written notice incorporated into the lower edge of the frame itself, thus becoming a part of it. [Fig.1] It states:

This Picture was painted by Signor Canaletti who took the View from the Window of the small Cottage at the end of the Inclosure next Mr Crowle’s Garden, – & the Figures added by him at Percy Lodge. It was finished June the Eleventh 1747.(3)

The Dulwich curator declared that ‘nothing is known of “Mr Crowle”’, something of a challenge to a local historian, though one to be pursued later. However, it was also clear to anyone with local knowledge that he had been misinformed about the topography of the river bank and the viewpoint chosen by Canaletto. He writes that the

site of [Mr Crowle’s] garden can be readily identified. It was on the land now known as Romney Island, which was formed when the wall on the left was demolished in 1794 and a lock-cut was made leading from the Thames to Romney Lock and then back to the river.(3)

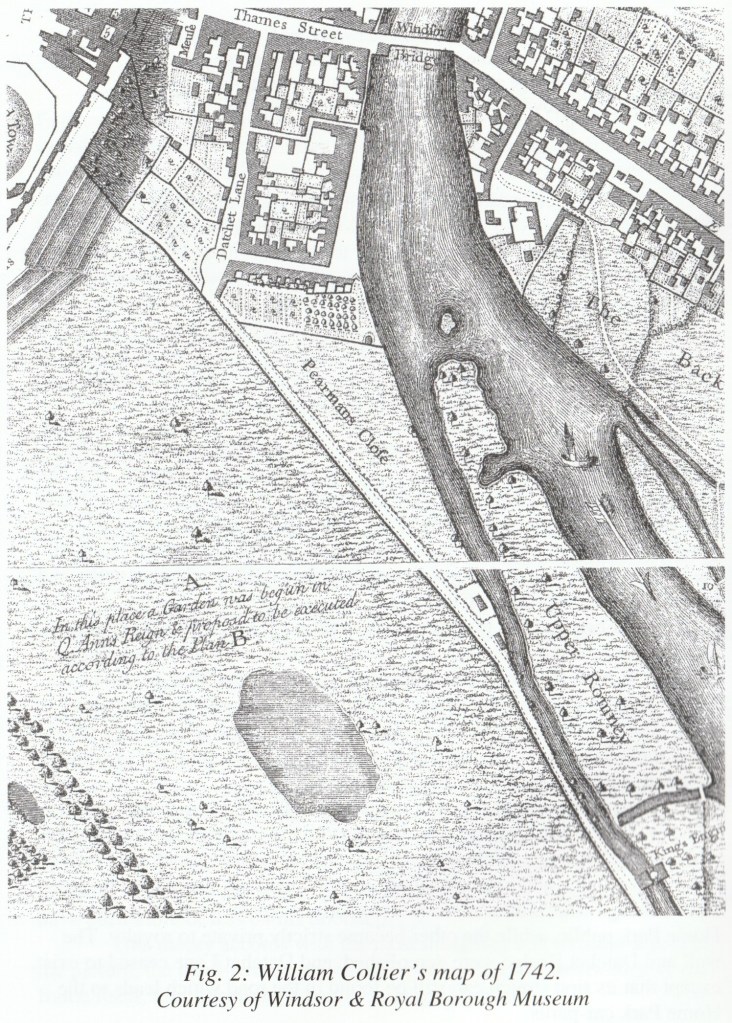

But Romney Island is a natural not artificial formation, shown in William Collier’s plan of 1742 made for the Duke of Marlborough; in 1794 it was the island itself which was sliced through to create the lock. [Fig.2] The tip of Romney Island can be seen in the painting, the Eton bank being glimpsed on the far side of Windsor Bridge. Canaletto presumably took his view from the nearer of the two cottages marked in Collier’s plan at the end of land labelled Pearman’s Close.

The high wall in the painting divided royal land, the Little Park, from Datchet Lane on the river side, the highway to Datchet Bridge, popular as a crossing because unlike Windsor Bridge it was toll-free. That would be the road Canaletto took himself, his precious canvas scarcely dry beside him, when he left Windsor for Percy Lodge. In the painting a grand coach rolls along the lane towards the town and could represent the one sent to collect the artist, added by him with the other figures.

The landscape changed dramatically in the mid-nineteenth century when the South Western Railway was constructed (perhaps the foundations of Canaletto’s cottage lie underneath). By the agreement struck then between town and crown a new road was made through the Park, leading to the new Albert Bridge. One side was made a recreational space for local people, Home Park public, while the other became strictly private to royalty. The wall and Datchet Bridge were demolished, and Datchet Lane ceased to exist, except that its first stretch can still be found in the road which leads to the Home Park car-parks.

The scene captured by Canaletto is, however, one which had been familiar to generations, the drainage ditch and the distant washing line reminding us of Falstaff’s fate in The Merry Wives of Windsor when he is unceremoniously dumped from a laundry basket into ‘the muddy ditch close by the Thames side’. But that view has been lost. Because of the railway line no artist today could combine river and castle as both Canaletto and the water -colourist Paul Sandby could. Roughly twenty years after Canaletto, Sandby (1730-1809), whose paintings also combine architectural detail with human figures, painted a water colour from a very similar viewpoint to the Venetian artist’s, likewise showing Datchet Lane, the Castle, the river and Romney Island, and including the little summerhouse by the Thames which features in Windsor Castle.(4) [Fig.3].

The Sandby connection helped to identify the mysterious ‘Mr Crowle’. In her book Views of Windsor: Water Colours by Thomas and Paul Sandby, Jane Roberts names him as Richard Crowle, who in 1755 made an exchange with George II of the freehold and leasehold land he owned in Windsor, with property belonging to the crown in Yorkshire.(5) Richard Crowle was an Inner Temple lawyer, and the assignee of various royally-owned farms, fisheries and fowling rights in aan Stoneferry, Wawne, and the former abbey of Meaux in the East Riding.(6) He also possessed a manor house in Yorkshire at Springhead. Crowle had been acquiring land in Windsor for some years, both buying outright and acquiring leaseholds. The Windsor Hall Book for 21 January 1736 records the renewal of a lease to Richard Crowle Esquire ‘of several parcels of land’ let to Mr James Pearman deceased for 40 years by a lease of 1697 in Datchet Lane, at 5 shillings a year plus a ‘fine’ [fee] of ten guineas, reduced in October to five as the property had been found to be of less value than first thought.(7) The name ‘Pearman’s Close’ on the map is therefore explained. The lease itself, a handsome parchment document drawn up later in October adds more details, with Crowle’s signature and seal.(8) [Fig.4]

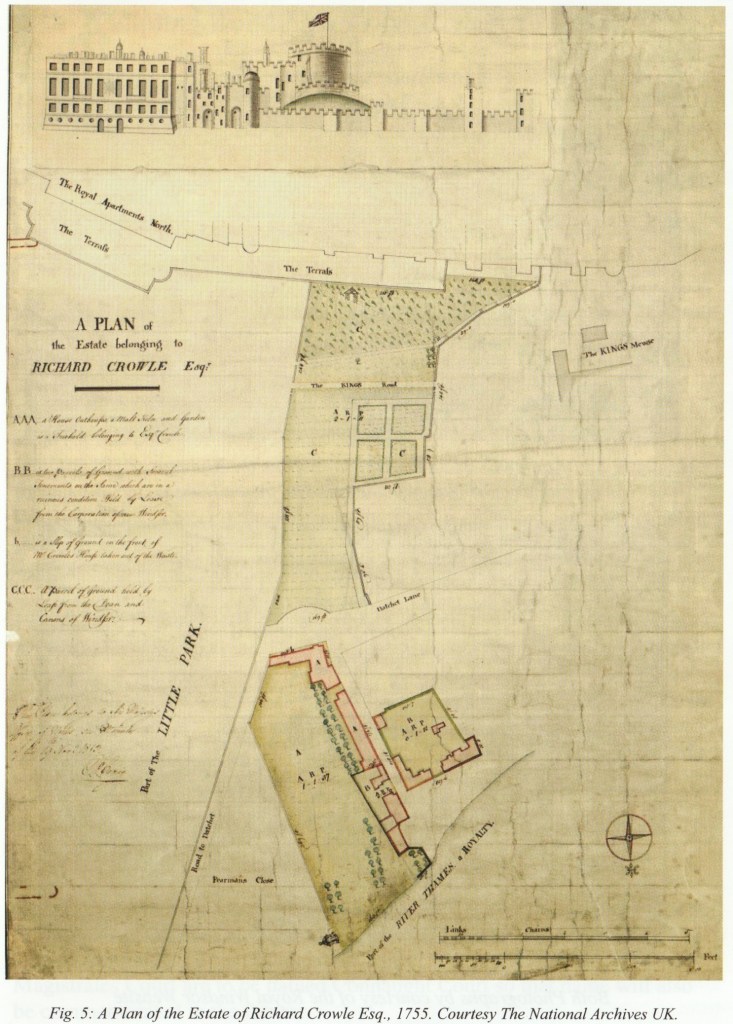

An Act of Parliament in 1755 authorised the exchange.(9) The Public Record Office holds a semi-pictorial plan drawn up for the purpose of Crowle’s Windsor properties, which includes little drawings both of the summer-house by the river and another just under the Castle walls which can also be seen in the Canaletto.(10) [Fig.5; key at end of article] There was some dispute over the valuation of the two estates; Crowle petitioned the Commissioners of the Treasury since he reckoned the value of his Windsor property, which included his house and a ‘malt kiln’ [brewery], as £742 more than did His Majesty’s Surveyor – nearer to £75,000 today – but in the end agreement was reached.(11)

Two years later, on 21st June 1757, Richard Crowle died. He had drawn up his own will just twelve days earlier while at Bath, which suggests a desperate attempt to recover health at the spa.(12) Ironically, although written on his death-bed it gives him life and personality, and reveals a personal tragedy. His first concern is to make provision for his wife (unnamed, but held by him in ‘affectionate regard’), and his son William who is dependent on her. He explains that his wife had, while ‘enceint’ [pregnant], met with ‘many and sudden overturns in a coach and other Accidents which reduced her to a state of Stupor for many hours’, with the catastrophic consequence for the child that he was born to ‘an absolute state of Incapacity and Incompetency of managing his person or Estate’. The rest of the will — five pages — is concerned with arrangements for his other son and heir, John Charles. Clearly worried that a young man who had not finished his education should not have too much too soon, he appoints trustees to run the many-propertied estate until John Charles shall reach his twenty-fourth birthday. He recommends that his son receive an ‘academic and liberal education’ by studying for a year at Cambridge, followed by two years at Geneva or some other foreign academy. Perhaps he feared reluctance, as the trustees are instructed to give John Charles an annual allowance of £250 if he follows his father’s wishes, £25 if he does not. A codicil added more bequests to family and servants, including one to his servant Thomas Morris of all his clothes, £5 to buy mourning, a year’s wages, and a further sum of £20, but with the wish ‘that he would have endeavoured to have deserved more from me’.(13)

The back of Crowle’s house while he lived in Windsor is seen in the middle of Canaletto’s painting; the side and something of the front was pictured in another Sandby watercolour of about 1790.(14) (It would have stood where the Station Master’s house was built, now offices). Windsor’s wooden bridge to Eton is depicted, but most of the lower end of the town is hidden behind trees. Little building of that period remains today, though there are Georgian houses opposite Windsor and Riverside station, and another, now the River House restaurant, may be the red-brick building on the water front, though there was also a brewery. But the large building on the skyline is an anomaly — there were substantial buildings near the river, such as Wren’s house, but there should not be anything so dominating in that part of Windsor, where most of its poorest citizens lived. Perhaps this building was, like the human figures, added after the artist had left. (Canaletto did not always worry about strict likeness — when in 1754 he painted a view of Eton College across the Thames he distorted the size of buildings, changed their relationships to each other, and included some that did not exist.)

How much did the artist receive for his picture, and how long did he take to complete the painting? There is a receipt in the Alnwick archives written in Italian by Canaletto himself on 21st July 1749, acknowledging the sum of 32 guineas for the companion painting, Syon House.(15) Some answer to the second question comes in a letter from Smithson dated 2nd July; he says that ‘Mr Canaletti has begun the picture of Syon’— if the similarly-sized painting of Windsor Castle also took not much more than three weeks to complete, it was an amazing feat.

The questions raised by the extraordinary note framed with the picture are harder to answer. Who wrote it, and why was it thought so important? Perhaps a graphologist could show if it is Smithson’s writing; he seems the most likely candidate. Is the current frame the original one, or was it reframed many years later? There was some reframing of paintings belonging to the Northumberland estate in the 1820s, but no record that this was one of them, and when work was done on the pictures in recent years the conserver gave his opinion that the frame was an eighteenth-century one. It does, in any case, match that of Syon House.(16)

What is the full explanation of the connection between ‘Mr Crowle’ and the painting? Perhaps he was not only entrusted with making the local arrangements for the commission, but also provided Canaletto with lodgings while he painted, the central positioning of his house becoming a graceful thank you. It is at any rate pleasing to think of the Venetian artist coming to Windsor, walking through the meadows by the Thames below the majestic Castle and creating his masterpiece in summer sunshine.

Hester Davenport

Figures

Fig.1: Inscription on the frame of Canaletto’s Windsor Castle. Courtesy of The Estate of the Duke of Northumberland.

Fig. 3: Paul Sandby: The North front of the Castle from Datchet Lane near Romney Island, c.1785. The Royal Collection © 2007 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II

Fig. 4: Crowle’s seal and signature 15 October 1736. Courtesy of The Berkshire Record Office.

Fig. 5: A Plan of the Estate of Richard Crowle Esq., 1755. Courtesy The National Archives UK.

Key for Figure 5

- AAA a House Outhouses a Malt Kiln and Garden is a Freehold belonging to Esqr Crowle.

- BB is two parcels of Ground and Several Tenements on the Same which are in a

ruinous condition Held by Lease from the Corporation of Windsor. - b. is a Slip of Ground in the front of Mr Crowle’s House taken out of the Waste.

- CCC A Parcel of Ground held by Lease from the Deans and Canons of Windsor.

References

- Canaletto in England: A Venetian Artist Abroad, 1746-1755, Yale Centre for British Art, Yale University Press, 2006, p.138. Smithson’s grandfather made money as a haberdasher, but was awarded a baronetcy from Charles II for his royalist support. Smithson himself married into the Percy family and through the death of his wife’s brother inherited both property and titles. See the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for more details.

- Originally known as Richings Lodge, the house was bought by Seymour’ s parents-in-law, the Earl and Countess of Somerset, and renamed Percy Lodge by the Countess.

- As note 1.

- Reproduced in Jane Roberts Views of Windsor Castle: Water Colours by Thomas and Paul Sandby, Merrell Holberton Publishers Ltd, 1995, p.75.

- Ibid, p.76.

- From the Victoria County Histories, ‘Middle Division: Wawne’, A History of the County of York East Riding: Volume 7: Holderness Wapentake, Middle and North Divisions (2002), pp.181-204.

- The Second Hall Book of the Borough of Windsor 1726-1783, edited by Jane Langton, Royal Borough of New Windsor, 1973, pp.35 & 38.

- BRO WI/AT/1/40. The land which had been enclosed by James Pearman is described as ‘waste land’ at the ‘South End of the King’s Slaughterhouse’, so the sights, sounds and smells of the area would not always have been idyllic.

- PRO T1/363/33. ‘An Act to Enable his Majesty to Grant the Reversion of divers Lands and Hereditaments, in the County of York, in Trust, for Richard Crowle, Esquire, in Exchange for Houses and Lands near his Majesty’s Palace of Windsor; and for other Consideration to be paid for the Same.’

- PRO Work 34/175.

- PRO T1/363/34, 35.

- PROB 11/831.

- Neither will nor codicil were witnessed. On Ist July 1757 William Crowle, a Trustee and nephew, appeared before a Public Notary to swear an affidavit that the handwriting of the will was his uncle’s. Thomas Morris did likewise for the codicil, even though he must have been illiterate as the signature was a surrogate’s. It probably helped that Crowle was well-known in legal circles.

- Roberts, p.77.

- The receipt is illustrated and the letter quoted in Canaletto in England, p.126.

- Thanks to Clare Baxter, Archivist of the Northumberland Estates, for this information and for discussing the issues with me.