Published in Windlesora 12 (1993)

© WLHG

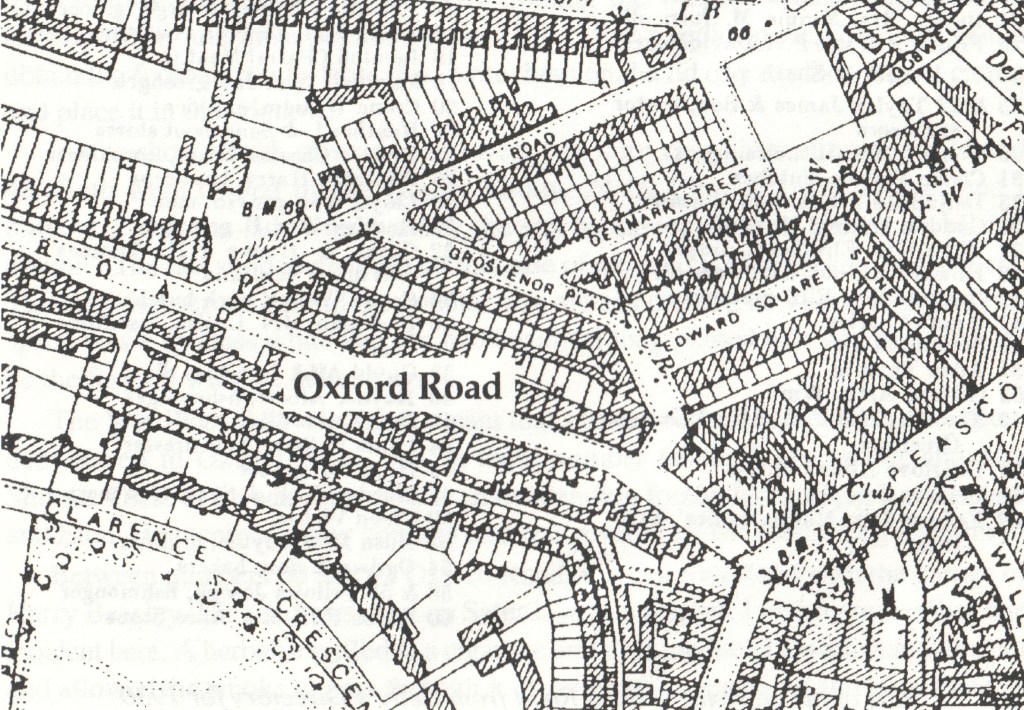

When Ward Royal was completed in 1969, I commented to the late Alderman John Proctor on the hideousness of the structure. He replied that he believed that in years to come people would appreciate the architecture. I was astounded when the design gained a medal and diploma from the Ministry of Housing and Local Government. My mind often goes back to the time when, as a lad of ten, I frequented the area.

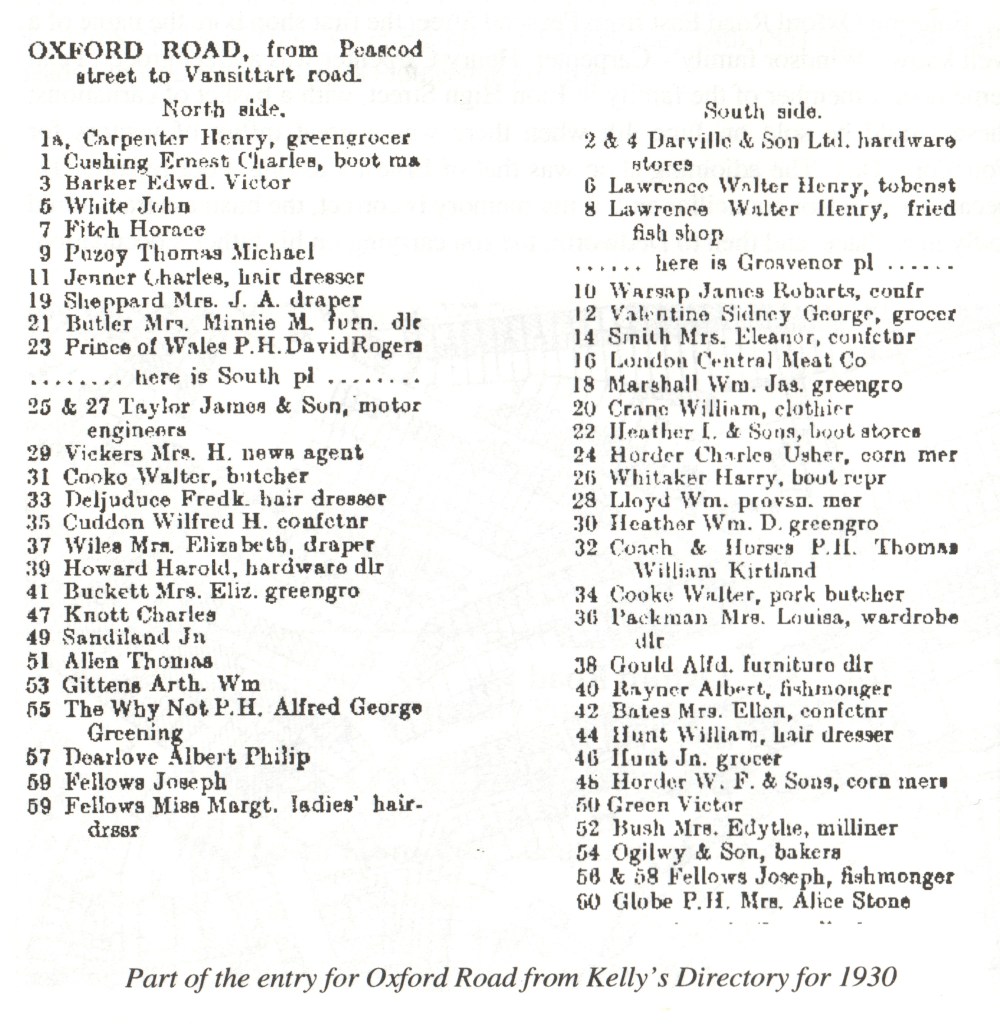

Entering Oxford Road East from Peascod Street the first shop bore the name of a well known Windsor family — Carpenter. Henry Carpenter was a greengrocer. I can remember a member of the family in Eton High Street, with a basket of carnations; these would be sold on June 4th when there was a great influx of visitors for Founder’s Day. The adjoining shop was that of Ernest Cushing, boot repairer. He became a Windsor councillor and, if my memory is correct, the business transferred to Sydney Place, and then to Dedworth, the son carrying on his father’s occupation.

Number 11 was the shop of Charlie Jenner, a hairdresser. No fancy styling there, ‘short back and sides’ was the order of the day. The familiar barber’s pole was affixed to the exterior of the premises, a rare sight these days.

Further along the road was James Taylor and Son, cycle engineers. This is where I obtained my first bicycle. My father had saved up for years to make that purchase. Miss Wiles had a draper’s shop that sold ladies apparel and bore the name ‘The Little Wonder’. At the shop of Miss Florence Carter one could obtain sweets thathave long ceased being bought by children such as ‘tiger nuts’, ‘locust beans’ and ‘gob-stoppers’ which were huge round sweets, difficult to get into the mouth and changed colour at each suck.

On the opposite side of the road was Darville & Son. These were drab and neglected premises that sold hardware and were connected to their provisions, china and Post Office premises in Peascod Street. Our next shop is that of Wally Lawrence, tobacconist. Wally was a bit of an entrepreneur, taking bets across the counter, also opening a fish and chip shop in the adjoining premises. My grandfather would visit the shop to obtain tobacco for his clay pipe. The tobacco was called ‘shag’ and was contained in a glass jar from which it would be taken out and rolled on paper so that it could be taken away in a tube.

In this walk down memory lane we are now at the junction to Grosvenor Place, but keeping in Oxford Road we come to Warsap’s, confectioner. This shop had an upright marble slab on the counter, inscribed with the words ‘Soda Fountain’ and different kinds of drinks could be obtained there. Adjacent to this shop was Valentines’s, a provisions shop which had its rear in Grosvenor Place. Here milk was sold. There were none of the modern health precautions like bottles, cartons or expiry dates, a jug was sufficient.

Still keeping on this side of the road we came to number 20, advertised in the trade directory as ‘clothier’, but this in no way describes the shop of ‘Billy Crane’. There were hobnailed boots, together with articles of clothing hanging from the ceiling and the shop window was a real jumble of shirts, illuminated in the darkness by a solitary gas mantle. On Saturday evening the window would receive much attention from the male population, for ‘Billy’ had a radio in the shop and would obtain the football results from this, write them on the lid of a cardboard boot carton and place it in the window.

In this short stretch of street there were two corn merchants at numbers 24 and 48. Both were owned by the Horder family, 24 by Charles Usher Horder and I remember that the lads would annoy the son by saying “Usher, Usher, we all fall down!”. The last shop to mention on this side of the road is Ogilwy and Son, bakers. The lady that served behind the counter was always dressed in Victorian attire. Her apron was a spotless white and she had beautiful long plaited hair which seemed to be the fashion with the ladies then.

The Ward Royal development meant that some seventeen dwelling houses were demolished in Oxford Road, among them number 68 the home of Mr and Mrs Shuttle. Dick, as he was known, was an outstanding footballer, playing for Windsor and Eton. He received many honours and was revered by the footballing fraternity.

Between numbers 60 and 62 Oxford Road was Goswell Road with the garage of Harry Beasley. His yard was used on Saturdays as a market. I vividly remember one incident here. A herbalist puffed at a cigarette and then produced a white handkerchief and allowed the smoke to pass through it. A brown stain appeared and he warned us of the hazards of smoking. Also in Goswell Road, at number 101, was the establishment of Harry Newcombe, cycle dealer. In those days, as far as I can remember, cyclists were not required to have a rear lamp. Front lamps were mostly of the type that used paraffin, and often caught fire. Those who could afford it had carbide lamps, and it was to Newcombe’s that one went for this fuel. It produced a very pungent smell. The most expensive lamps were highly polished and had a small green glass window on one side and red on the other. The cyclist would know which was port and starboard whilst cycling.

At 24 Denmark Street we found the shop of John Shellard. This was what we children called a sweet shop and I remember the glass jar of yellow lemonade powder that was always in the window. Mr. Shellard carried on a sideline of hiring out wheelbarrows, mostly the costermonger type. Also in Denmark Street was the Holy Trinity Mission Room, which carried on much useful work, especially among the young people.

Passing on into Edward Square, one would find that the focal point was number 58 where my granny and grandad resided. Affixed to the exterior of the house was a shrine. This consisted of an illuminated scroll, contained in a glass frame, recording those from the street who had given their lives in World War 1. Fastened on each side of a wooden overhead projection were two tins containing flowers and these were constantly replenished. Granny spent much of her time at the front door and she would always know what was going on. Mothers who could not afford to take their children to a doctor would come for a consultation. The suggested remedy for ringworm would be to apply a copper coin. For whooping cough the advice would be to take the child to the adjacent gasworks and breathe in the fumes. The funny thing is, it often solved the problem. Granny was often be required to do the laying out when people died. When asked to engage an undertaker, it would always be Mr. Martin of Eton, and he would press a coin in her hand for the recommendation. Granny insisted that it was to be Mr Martin for her funeral, and it was. Grandad was a painter and decorator and in the winter, when there was very little outside work he found interior work at Holloway College at Egham and walked to and fro each day.

Edward Square was a cul-de-sac with a high brick wall forming a barrier, but this was easliy climbed, as bricks were removed to enable us to scale the obstruction and reach the premises of the Windsor Steam Laundry.

Another interesting feature to disappear was the Corporation Depot in Alma Road. Windsor people with their Berkshire accent would call it the ‘Loca Board’ meaning the ‘Local Board’. I must say that it was more interesting for us children to observe what was going on at that depot than it would be for today’s children at Tinkers Lane. What a sight it was to see the magnificent horses, resplendent with their highly polished brasses. There were tar-tanks containing hot tar to be spread on the roads with the adjustable brush and another tank which was used to contain the muck taken from the drains using a long handled scoop. The most attractive vehicle was called the fever cart. It was made of mahogany coloured wood and was driven by Mr. Stingmore. Its purpose was to collect bed linen from houses that had contagious diseases so that it could be fumigated. Mr. Stingmore was also the rat catcher — no doubt these days he would have been called a rodent operator.

A simple pleasure after returning from school would be to watch the men clocking off. All manual workers had to insert their cards to verify their times of commencing and finishing work. It was the constant ringing of the clock bell that was the main attraction to the children. But I suppose the job we lads all fancied when we left school was to be driver of the steam roller.

Fred Fuzzens