Published in Windlesora 23 (2007)

© WLHG

Advantages of Commerce

‘I am wonderfully delighted to see a body of men thriving in their own fortunes, and at the same time promoting the public stock; or, in other words, raising estates for their own families, by bringing into their country whatever is wanting and carrying out of it whatever is superfluous.’ Joseph Addison (1672-1719) Essayist, Whig.

Creator of The Spectator and The Tatler (Many thoughts of many minds, 1868 Henry Southgate)

Francis Tress Barry (1825 – 1907) was just such a man. At 16 years old, he joined a merchant company in Bilbao and at 22 years old was consul of the Biscay Region of Spain. He and his brother-in-law developed the San Domingos copper mine in Portugal (1859 – 1964), building a 15 km railway to Pomirao Harbour on the Guardiana river, transporting the ore downstream to the Mediterranean port of Vila Real de San Antonio and on to London, where he had his office headquarters. For his building of an autonomous settlement village for the mining families, he was decorated by Portugal and became Baron de Barry.

With his wealth, he purchased the St Leonard’s Estate in Windsor in 1872, building a prestigious mansion which dominated the skyline. As a result of this, he became a trustee of Clewer Green School, which had been established by the Harcourts, the previous owners of the estate, and received a Baronetcy from Queen Victoria in 1889 with the Jubilee medal with bar for his philanthropic work. His election as MP for Windsor was reported in the Clewer Parish Magazine for May 1890.

‘F.T.Barry, conservative candidate, returned at a recent general election by a large majority. Mr Barry, our new M,P is a parishioner of Clewer and resides part of the year at St Leonard’s Hill.’

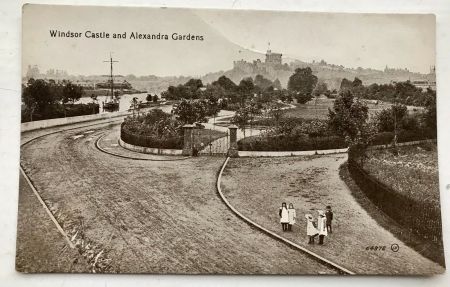

The name of St Leonard’s Hill lives on, but what is remembered of this commercial genius? The drive up to the mansion used to be known as Barry’s Drive but is now St Leonard’s Hill, Windsor Forest. How many visitors, or residents for that matter, know that the road along the river front from the railway arch to Goswell Lane is known as Barry Avenue or that the park which is alongside it, known as Alexandra Gardens, owes its existence to Sir Francis?

A schedule of 1862 relating to an unknown map shows 5 acres 36 perches of meadow belonging to Middlesex Hospital, managed by Charles Hand who had an orchard close by. Windsor Borough, as a Sanitary Authority, purchased the land in 1889 for £3,000, a large sum of money in those days, ‘To hold and to the use of the purchasers in fee simple for the purposes and subject to the provisions of the Health Act 1875.’

In 1902 part of this meadow was mortgaged to a Sarah Ann Taplin of Arborcroft, Slough from Windsor Borough and Sir Francis Tress Barry, ‘being desirous by means of a gift for the permanent benefit of the said Borough and the public to commemorate the Coronation of His Majesty King Edward the Sixth and her Majesty Queen Alexandra’ paid off the £1,225 outstanding and the 4 acres 3 roods was transferred to Windsor for a public park.

The piece of land between the railway arches and the Middlesex Hospital land, now part of Clewer Without, had been held in trust under the will of Arthur Vansittart (died 22 April 1859) of 8th November 1858, for 99 years. As one trustee died so another was appointed, and in 1904 the trustees were Arthur and Gerald Stovell. As no money had actually been raised during the term of the will, it was no doubt derelict and under the terms of New Windsor order 1903 and the local government Board’s Provisional Order Confirmation Act 1903 the Corporation are empowered to ‘purchase and take’ this land for the purpose of public walks and pleasure grounds valued at £3,800. However, Sir Francis Tress Barry paid £1,985 towards this amount in order to extend Alexandra Gardens with the addition of the triangle from the railway arches along Thames Avenue, renamed Barry Avenue. The whole of the piece of land along the Thames from the railway arches to Goswell Lane is now the walkway as we know it. It was banked as a flood barrier. The late Gordon Cullingham was very scathing of this fact, writing ‘Then came the Dyson Embankment, now Barry Avenue, to keep out the floods – this it did until outflanked by overland flooding which the embankment kept in the town in 1947’.

Without further research, it is not possible to be sure of the thinking behind the original purchase of land in 1889, but by quoting the 1875 Public Health Act it must have been more than civic pride in providing Alexandra Gardens as a fashionably healthy recreational venue. 1875 was the date of purchase, by Windsor, of land for the treatment plant on Ham Island under the Public Health Act (Windlesora No. 21 p.34) and since that date Windsor had fought to bring Clewer into the Borough sewage system. Dedworth and Spital were first, and in 1889 succeeded with half of Clewer, Clewer Within, with the boundary along Goswell Lane. Could it be that they had hoped to use the land for a Sewage System extension? Storm drains were, in fact, laid across Alexandra Gardens from the car park with the outflow into the Thames at the slipway, and this must have been done before they were laid out to gardens after 1904.

My Memories of Alexandra Gardens

My association with the gardens spans about twelve years of my young life and started with my parents’ move from the top flat of Osbourne House (opposite the Edward VII Hospital), which made way for the bus depot, to a semi-detached house opposite the County Boys’ School, now Windsor Boys’ School, in Maidenhead Road.

As the wife of a rising young man of a business which would become a household name, my mother had to have ‘help’. The first was Connie, from the orphanage run by the Sisters of Mercy in Hatch Lane. She was paid half a crown a week pocket money (12½ old pence). As a girl of 14 years brought up by nuns, she had been sheltered and was less than helpful and needed to be treated as another child rather than an adult, spending most of her time swinging on the gate, talking to passers-by. However, in those days of few dangers and little traffic, she could at least push a pram. My pram was a high, gleaming coach built Silver Cross with clips at the foot which could lower it to make a push-chair for a seated child.

Every fine afternoon, our journey would be the same. We would turn left from the house along Maidenhead Road, turn left into Vansittart Road and then right, passing the green painted corrugated iron fence surrounding the Windsor Baths and peer through the turnstile gateway where Mr Horder sat in his little ticket office. From here, we could see the backwater of the river with its concrete steps and diving boards. It was here that I learned to swim and acquired a lifelong dislike of mud between my toes.

So on under the railway arch where a shout would echo for ages afterwards, and past the locked gate which led to the walkway of the Windsor Rowing Club, which also served as a division in the baths and separated the girl swimmers from the boys. From here, it was only a short distance to the bottom gate to Alexandra Gardens. Once in the gardens we would walk along weed free paths, past the tennis courts to turn left past the central group of trees with the round garden and the drinking fountain surrounded by flagstones, out of the middle gate and so to the riverside walk where we would feed the ducks and return the way we came in order to be home for nursery tea.

The gardens were also the haunt of the local nannies and on fine afternoons all the green painted iron seats would be filled with ‘dragonesses’ and nursemaids with grey hats and coats gossiping or eyeing each other and comparing the wearing apparel and baby carriages of the opposition with their own, no doubt returning home either with their head held high or determined to persuade their mistress to up the quality of their own turn-out.

As I grew older and relegated the pram to my brother, and later, when we could both run about, our companion changed, but the venue did not. By then, we were old enough to explore the wild places of the gardens. The most exciting part was the clump of trees just inside the first gate, which remained a tangle of undergrowth and was to us a foreign jungle, and which hid the two small sheds where the tennis club stored their deck chairs and the rustic summer house clad with tree trunks and split branches. To go over the fence and up the bank to the railway lines was really frightening, and it was always my job to rescue my daredevil brother from the top of the bank when our chaperone was deep in conversation and not looking our way. We regularly visited the brick and slate roofed toilets, on the other side of the garden. They were really out of bounds to us in case we caught germs, but to us, they were like secret houses hiding behind their laurel hedge.

My grandfather owned a sweet shop in St. Leonard’s Road and had the licence to fill the chocolate machines around the town. He would take the boxes to the various sites on his bicycle, unless I was with him, and we would walk. It was my delight to go with him to refill these machines with the little red penny bars of Nestle’s chocolate. One of these machines was situated just inside the main gates next to the weighing machine. Near it was the large round fish pond surrounded by a low concrete wall. I would sit on this wall and watch the red and gold fish swimming in and out of the water-lilies and round the fountain islands, which sprayed water into the air to splash in the clear water of the pool. Maybe it was these that protected the fish from the numerous herons in the area.

A walk along the path towards the toilets brought us to another machine. I loved to run to the plane tree and run clockwise around the green plank seat which surrounded it and see the whole gardens. There was the bandstand and the gate to the road and the river, the main gates and the gun, the pond, the flower beds and bushes, the toilets and the gardeners’ shed in the shrubbery, where water was boiled for the tea for The Twenty Tennis Cub, the tennis courts and their buildings, the wild woods and the bottom gate, the path along the herbaceous border and I was back to the beginning again.

During the war, the iron gates and the railings, topped with points like spears, were cut away for the war effort. It was very sad to see the acetylene torches cut into the metal and the portions of the railings thrown into a pile in the lorry. All that was left were the rusting stubs in the cement that topped the low wall. There was a feeling that the peace and tranquility of the gardens had been removed forever.

The golden carp were also taken away, and the round pond filled with soil and annuals. The chocolate machines were removed and all the wild places were cleared to make the gardens more neat and tidy for the tourists. After the war, the world was no longer a place where leisurely band concerts were required, and the bandstand fell into disrepair and was taken down. It is still possible to find the occasional stand of railing around Windsor which escaped the chop, but most are just the low concrete walls which show where they once were. Ironically, it appears that the sacrifice was useless since it is believed that the ship carrying the war effort railing was bombed on its way around the coast to its destination, and Alexandra Gardens’ glorious gates are at the bottom of the North Sea.

I visited recently, and the present day Alexandra Gardens is a mere shadow of the previously exciting place. With no gates and railings, the round garden is gone, and the grass is closely mown, and it all feels sanitized. The tennis courts are used for clock golf and there are bicycles for hire and ice-creams in the pavilion. The only other thing left is the original gardeners’ stone-built store, now behind a high fence, and there are steps leading to the coach and car park, which was once the coal yard. I prefer to keep my childhood memories.

Valerie Batt-Rawden

Notes

Thanks are due to:

The present Baronet Sir Edward Tress Barry, for his help and interest in my research on his great-great-grandfather, Francis Tress Barry.

David Chandler, who furnished me with copies of the deeds of the Alexandra Gardens land transactions from the archives at Maidenhead Town Hall.

Gideon Smith, Tinker’s Lane, for information on Sewers/Storm Drains in Barry Avenue.

Other information from the Internet and Berkshire Record Office.

Further information can be found:

The Royal Windsor Website on the “Alexandra Gardens” web page which has a number of articles on the subject.

“Francis Tress Barry – A Forgotten Windsor Philanthropist” by Valerie Batt-Rawden in Windlesora 30 (2014).

“Windsor’s Riverside” by Raymond South in Windlesora 10 (1991).

Commemorating the opening of Alexandra Gardens