George Street

Published in Windlesora 20 (2003)

© WLHG

Walking from Thames Street down the recently renamed Jubilee Arch (formerly Station Approach) towards the row of elegant shops which back onto Goswell Hill, you can retrace George Street, but you cannot find any signs of this street today. It was a short street, but one with particular notoriety. Charles Knight wrote about it in his recollections: ‘There was a whole street of a vicious population where almost every house was a den of infamy. At the bottom of this foul quarter stood our gaol.’1 The whole of this area was swept away in 1849, after the Great Western Railway gained permission to bring a branch line from Slough into Windsor. The gaol had been moved in 1845 to the old workhouse in Sheet Street, next to the Infantry Barracks, where it remained until it was closed in 1854.

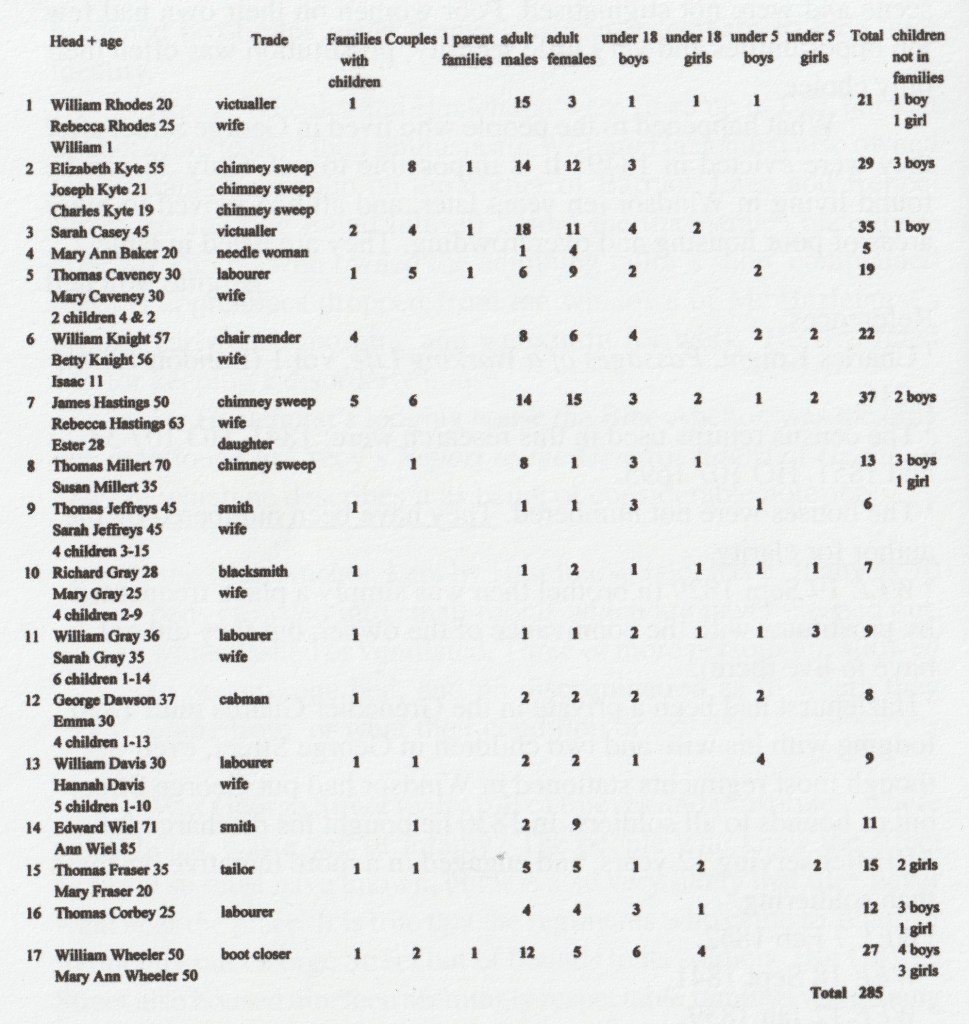

An image of George Street can be gleaned from the 1841 census returns.2 At that time there were seventeen inhabited houses in George Street, four were empty.3 There were 285 people living in these houses, which gives a density of 16.7 persons. But looking at table 1, it is clear that some houses must have been much larger and were evidently lodging houses or public houses. Only three houses, numbers 9, 10 and 11 were occupied by one family, although number 10 had one young female lodger who was said to be a dressmaker. There were 19 families in the street with 24 children between them. A further 20 children lived without evident relatives, the two youngest, just ten years old, were working as chimney sweeps. Altogether there were five chimney sweeps, four labourers, one waiter, one boot-closer, a hawker and a robe maker among the boys, and three lace makers and one cotton-spinner among the girls, who were between 15 and 17 years old. This leaves four of the young females without work. Most of the adults were single young males and females; the average age in this street was thirty. Many of the young males were itinerant workers such as hawkers or journeymen staying in the cheapest lodging houses in town. Just 98 inhabitants of George Street were local born. There were 16 adult chimney sweeps, but the majority were labourers. Of the 44 unmarried females living in this street 27 were said to be dressmakers, laundresses, lace-makers, needlewomen or charwomen, 17 had no job description, which indicates that they may have been earning their crust on the street.

A more vivid picture of George Street emerges from the Windsor and Eton Express newspaper files, especially the police reports. The first mention was in 1829 when Mr Haines, ‘a one-eyed brothel keeper’ was accused of assaulting Stephana Winter because she had not paid her rent.4 Three public houses were regularly mentioned, the Spread Eagle, the Rose and Crown and the Prince George, along with Mr Wheeler’s beer shop and Simon’s lodging house, but most notorious was William Hazlehurst’s5 lodging house and beer shop, the Blue Anchor.

Only two public houses can be positively identified in the census returns, numbers 1 and 3. Both also seem to be lodging houses. Number 1 housed fifteen young single males, but also two young females without job description. Mr Wheeler lived in number 17 and called himself a boot-closer. Five unattached females lived in his house. Three of these were only 15 and said to be lace makers or cotton spinners, but the reputation of Mr and Mrs Wheeler’s establishment does not suggest this sort of cottage industry. This leaves us with one public house, and two lodging houses to identify. Numbers 2, 5, 6 and 7 are possible candidates, but it is impossible to tell which was which. Mr Hazlehurst did not live in George Street at this time, but at his other establishment in Barrack Lane.

Numbers 4 and 14 were also interesting as they housed several young females, most of whom were without a job. It is likely that these girls were working as prostitutes. However, Ann Williams aged 20, who worked as a shoe-binder living at 4 George Street, was arrested for using foul language towards respectable women. The magistrate described her as a girl of the town, but released her after a reprimand.6 Mary Stephens aged 25, living in 15 George Street and said to be a charwoman was fined 25s for assaulting another prostitute in Wheeler’s beer shop.7 These girls were known as dollymops, a description for females who followed some trade during the days and carned extra cash in the evening in the street, just to make ends meet. In 1839 William Bragg the landlord of the Spread Eagle, William Wheeler and William Hazlehurst were prosecuted for keeping bawdy houses in George Street. Mr Wheeler’s beer shop was said to be ‘of the worst description, a den of infamy harbouring thieves and prostitutes’.8 During the trial of the three ‘gentlemen’ a number of ladies of the street were mentioned as operating from their bawdy houses and living in George Street; unfortunately none can be identified in the 1841 census returns as they were only referred to by their colourful nick-names, such as Fat Ellen, Black Hannah, Wraysbury Hannah, Biddy, Snook, Spital Bounce and the Sergeant Major.

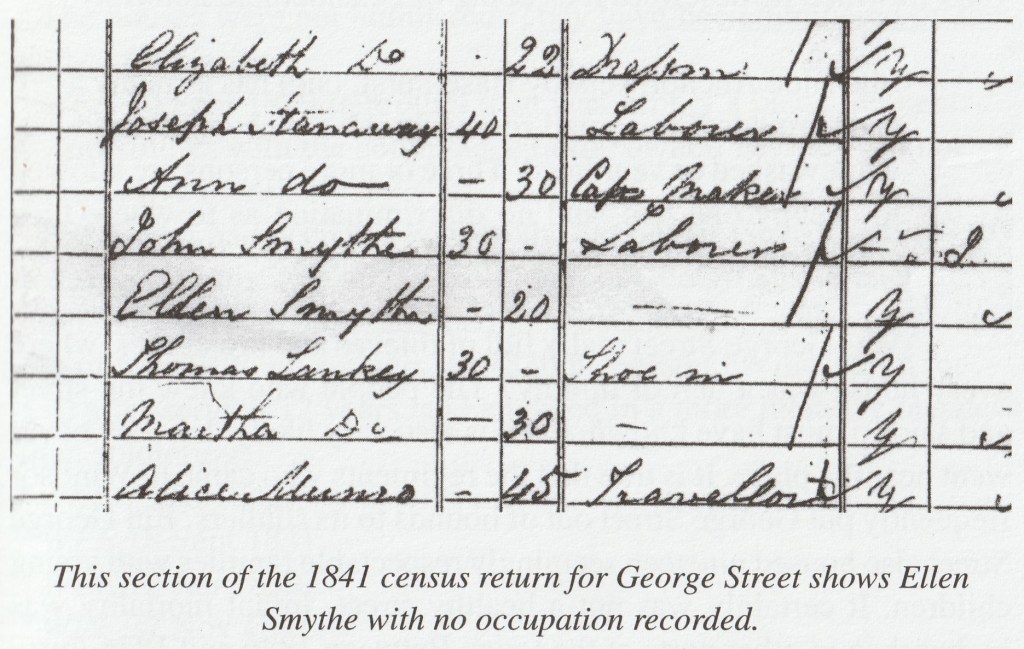

However, there are three possible candidates, Hannah Eggleton aged 15, Ellen Smythe aged 20 and Hannah Sullivan aged 16 lived at numbers 1,2, and 3 respectively. None had a job. Neither can any of the prostitutes who appeared before the magistrate, and were said to live or work in George Street be identified in census returns, except Mary Stephens and Ann Williams mentioned above. This suggests that when the census takers came to George Street, many of the hardened prostitutes made themselves scarce, perhaps to hide their identity.

Bragg, Wheeler and Hazlehurst were fined up to £40, but that did not seem to dent their enthusiasm. William Hazlehurst also owned the Brittania beer shop on the corner of Barrack Lane and Keppel Street. In 1842 he found himself before the magistrates once more after Mr Parker, who owned the adjoining tailor’s shop, complained that his apprentices dropped from the windows of Mr Hazlehurst’s brothel early each morning and were unfit for work.9 He was fined 14s for keeping a disorderly house.

Mr Hazlehurst’s lodging house the Blue Anchor, was the only one mentioned in Crecy’s Report to the General Board of Health of 1849 in which he describes it as being of considerable notoriety:

‘the Blue Anchor, kept by Haselhurst, (sic) has as many as 70 beds crowded into small rooms which are never cleaned out, whitewashed or ventilated. Three or more persons are allowed to occupy one bed, and no discrimination as to where they come from, or what their condition or sex.’ 10

Was George Street really full of thieves and prostitutes, where every house was a den of infamy? The people who knew the street and said so must have known, but it is also very likely that they never went near the place. It is true that the regiments who came to Windsor frequently put George Street out of bounds to its soldiers. But George Street also housed nineteen seemingly respectable families with young children. It certainly was not a healthy street. Infant mortality was higher than in other parts of the town. Between 1826 and 1836 thirty infants under five died in George Street; in Park Street with a similar number of families, only nine infants were buried during the same period.11 George Street was also a poor area; the first Windsor Ragged School had opened its doors there by 1845. It moved to a coal shed in Goswell Lane after the street was closed. Perhaps George Street was just full of the poorest and most destitute members of society, which generally included a criminal element. Prostitutes were part of this scene and were not stigmatised. Poor women on their own had few job opportunities and very little security; prostitution was often their only choice.

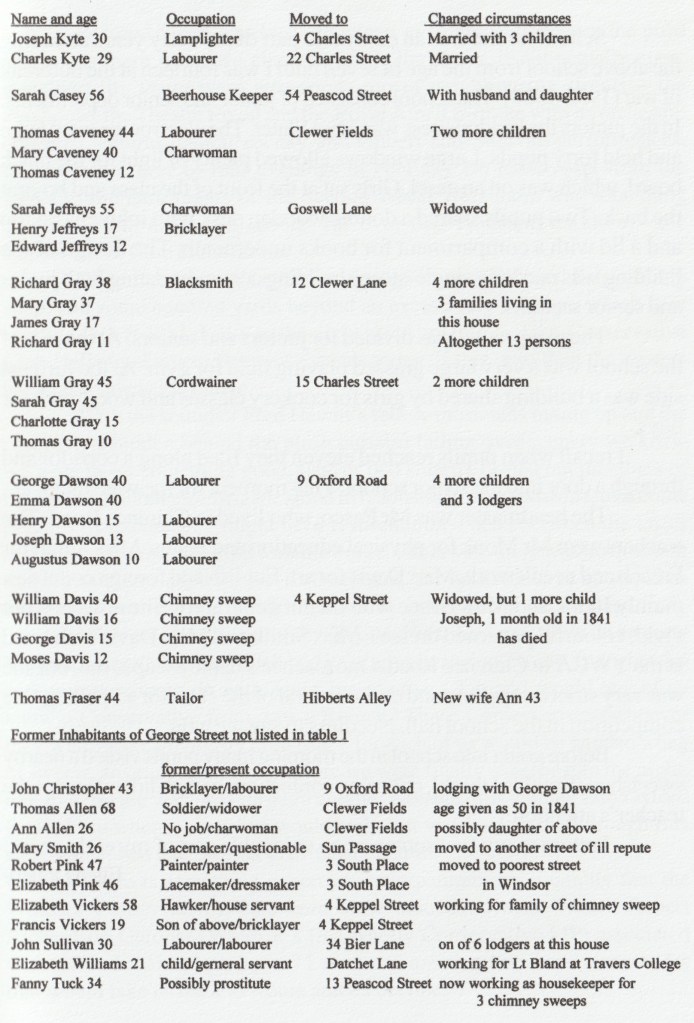

What happened to the people who lived in George Street after they were evicted in 1849? It is impossible to tell. Only 38 can be found living in Windsor ten years later, and all had moved to other areas of poor housing and overcrowding. They are listed in table 2.

Brigitte Mitchell

References

- Charles Knight, Passages of a Working Life, vol.1 (London 1864), p216.

- The census returns used in this research were: 1841, HO 107 37 and 1851, HO 107 1695.

- The houses were not numbered. They have been numbered by the author for clarity.

- WEE 19 Sept 1829 (a brothel then was simply a place frequented by prostitutes with the connivance of the owner, but they did not have to live there).

- Hazlehurst had been a private in the Grenadier Guards until 1830, lodging with his wife and two children in George Street, even though most regiments stationed in Windsor had put George Street out of bounds to all soldiers. In 1830 he bought his discharge for £10 after serving 12 years, and engaged in a more lucrative business than soldiering.

- WEE 7 Feb 1842.

- WEE 18 Sept 1841.

- WEE 12 Jan 18309.

- WEE 27 Nov 1841.

- E Crecy, Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Inquiry into the Sewerage, Drainage, and Supply of Water, and the Sanitary Conditions of the Inhabitants of the Borough of New Windsor (London 1849) p 17.

- Parish registers of St John the Baptist, New Windsor D/P 149 1/27 MF 92163.

Tables