Published in Windlesora 10 (1991)

© WLHG

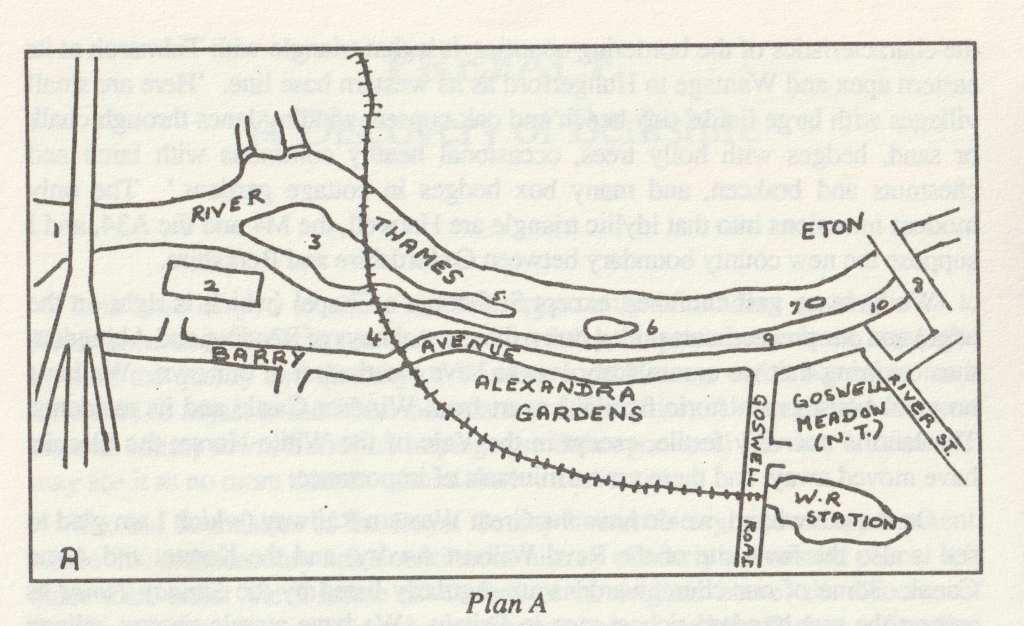

| 1. Elizabeth Bridge | 6. Jacobs Island |

| 2. Leisure Pool (site of the former Clewer Mead) | 7. Fireworks Eyot |

| 3. Baths Island | 8. Windsor Bridge |

| 4. Western Railway Viaduct | 9. Promenade |

| 5. Deadwater Eyot | 10. Jennings Walk |

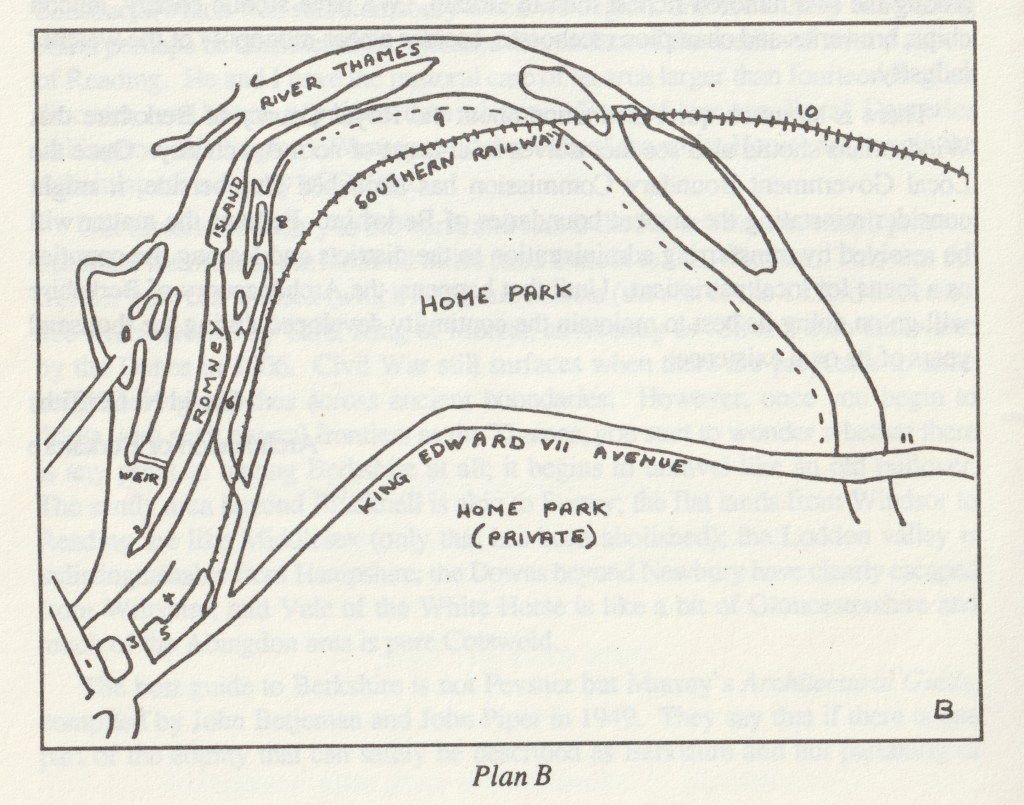

| 1. Windsor Bridge | 6. Romney Walk |

| 2. The Cobler | 7. Romney Lane |

| 3. Farmyard | 8. Romney Lock |

| 4. Thameside | 9. Riverside Walk |

| 5. Riverside Station | 10. Black Potts Bridge |

| 11. Victoria Bridge |

Windsor’s association with the River Thames has always been an essential part of its life. It may seem strange therefore that Windsor’s riverfront as we know it today is almost entirely the creation of the twentieth century.

The fact is that for centuries Windsor’s association with the river was primarily for commerce, not for pleasure or amenity. David Wilson’s The Thames. Record of a Working Waterway (Batsford 1987) gives a graphic and fascinating account of its subject. True, the river had some ‘pleasure’ uses — the author quotes a reference to one excursion from Abingdon to Oxford in 1555 ‘on a ribbon-bedecked boat furnished with amusements, card games, liquor and pies’. The purpose of the excursion was to take spectators to watch the burning of the Protestant martyrs Hugh Latimer and Nicholas Ridley in front of Balliol College. There is no record of similar excursions to see the burning of the Windsor martyrs eleven years earlier. Windsor, however, did benefit from the transport facilities of the river. Cotswold stone was brought downstream in the late fifteenth century for the building of the new St George’s Chapel. Sea-coal was brought upstream to the Castle as early as 1367.

Commercial uses predominated until the nineteenth century. Indeed the construction of canals and locks at the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century helped to create an inland communications network much more complete than the rivers alone could provide. Then came the railways. Now at last it was possible to transport heavy and bulky materials otherwise than by river. The change did not come overnight. But when it did come it was revolutionary. The rivers and the canals were no longer the normal routes for commerce. Gradually the use of the river for pleasure and amenity grew and use of the river for commerce declined.

One part of this change was the construction of riverside promenades at Windsor and many other Thameside towns. Even late nineteenth century pictures of Windsor show meadows extending to the river’s edge upstream of the bridge ~ where the promenade is now. True, there was some development either side of the bridge. But it was mainly commercial development. Datchet Lane continued near the river from Windsor to Datchet Bridge until its demolition in the mid-nineteenth century. Upstream a track connected the part of Clewer below the Castle walls (it is still necessary to make a mental effort to remember that the Castle is included in the Clewer, not the Windsor, entry in the Domesday Book of 1086) with Clewer Village and its ancient church — the traditional use of the track was for the taking of coffins. One of the customary names of the present River Street was Bier Lane — but it was not the only one.

By the end of the 1930s the Windsor Council was able to boast that virtually the whole of Windsor’s riverside (with much of what might be described as its ‘hinterland’) was in its control — from the Victoria Bridge on the Datchet Road almost to Clewer Church, some three miles in all. There were exceptions such as the Castle Waterworks adjacent to Romney lane, but these were few.

The Home Park

What is still the largest and most important of these ‘hinterland’ areas came under the control of the Council paradoxically because of the coming of the railways. After prolonged opposition by the Crown, the South-Western Company eventually in 1848-49 won the right to come into Windsor across the Home Park. The construction of the new road to Datchet further severed the Home Park and Queen Victoria agreed to the creation of the Home Park (Public). This area of 73 acres, held by the Council under licence from the Crown Estate Commissioners, has ever since been a venue for many recreational activities, both local and national. With its river frontage and its superb position beneath the Castle, it has been a priceless asset to Windsor. At the same time attempts by Eton College to purchase or lease land between the railway and the river were successfully resisted.

On the other hand, the towpath between the Victoria Bridge and the Albert Bridge, passing through the private section of the Home Park, was effectively closed to the public and has been ever since. In the proposals made in recent years for the establishment of a long distance walk by the Thames, this stretch is always cited as the most important gap. The solicitor to the Commissioners said at the

parliamentary enquiry into the Windsor Extension Railway in 1849 that the Crown was given power to ‘stop up the towpath against all the world but the Thames Navigation Commissioners’.

The Promenade

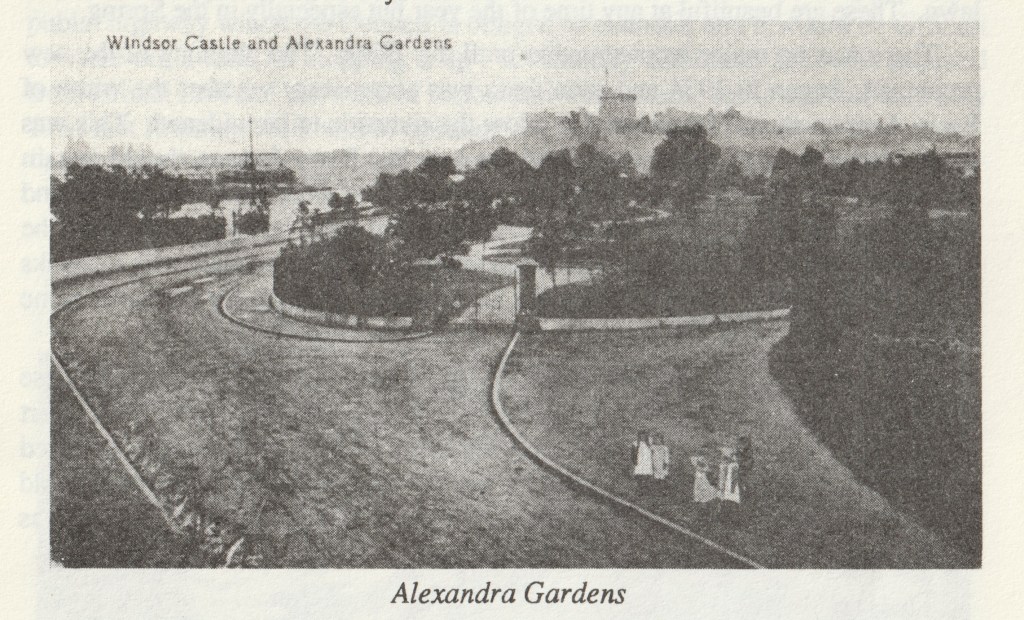

In the early years of the present century the riverside development comprising the Alexandra Gardens, Barry Avenue and the Promenade took shape. Barry Avenue, named after Sir Francis Tress Barry, Windsor’s M.P. from 1890 to 1906 and a local benefactor, approximately followed the line of the path from the town to Clewer Church. The Alexandra Gardens, between Barry Avenue and the Western Railway Goods Yard, provided a pleasant park with flower beds, lawns, a bandstand and fine views to the Castle beyond.

Regrets were expressed in later years that the whole site was not thrown open, with the lawns of Alexandra Gardens sloping towards the riverside without the intervention of a road. But at the time a road seemed essential and the road remained open for through traffic until the sixties when it was closed to cars at the railway bridge. In any case, with its fine avenue of lime trees, Barry Avenue adds to the scenic qualities of the riverside rather than the reverse.

Nearer still to the Castle was the National Trust land known as Goswells Meadow. This was purchased by the Trust as early as 1910 to preserve the view of the Castle and financed by public subscription (King Edward VII gave £500 and King George V, then Prince of Wales, £250). In 1936 the Windsor Council leased the land as a recreation ground and it has since been used for a bowling green and tennis courts. The Trust’s original objective has thus been safeguarded, while at the same time providing a useful addition to the town’s recreational facilities. The two dates incidentally, 1910 and 1936, tie in closely with the earlier and later stages of the development of the riverfront.

By the riverside itself a promenade was constructed before the First World War, from Jennings Wharf nearly to the Western Railway Bridge. It was not elaborate, but many photographs and postcard views show that it was very much used and appreciated. There were and are few ornamental features, with perhaps the exception of the magnificent weeping willows where the path projects towards the river between Jacob’s Island and Deadwater Eyot and there is room for a small lawn. These are beautiful at any time of the year but especially in the Spring.

There was no major reconstruction until the 1930s. The planning of the new promenade began in 1934 and soon there was controversy whether the width of Barry Avenue should be reduced to allow the riverside to be widened. This was successfully opposed and it was agreed not only that Barry Avenue should remain unchanged but that no trees should be removed. The work then went ahead and was substantially completed by 1936. At one point the work was held up by the flooding of the river and it is worth commenting that the promenade with its banks and walls acted as a flood barrier — the flood waters of 1947, for example, came over the river banks higher up and thence behind the promenade.

There were still gaps in the riverside walk and the problem posed by these were also tackled by the Council in the 1930s. A strip of land which formed part of Jennings Wharf was purchased from Courages in 1937/8 and a walk constructed with steps leading up to the street and the bridge. For this purpose a part of the old Toll House, so prominent in eighteenth and nineteenth century views, was demolished.

Romney Walk

Below the bridge, Romney Walk linking Thameside with the lane to Romney Lock, was made in the 1930s. Negotiations with the Southern Railway Company, who owned the land, had started in 1929 but during the period of financial stringencies that followed the Council came near to abandoning the project. A certain Mr W. J. Waldron of Winkfield, however, came to the rescue and advanced the money required. This enabled the negotiations with the Railway Company to go ahead and, when these were concluded, the construction of the Walk itself proceeded.

In 1937/8 the Council took over from the Crown Authorities the maintenance of Romney Lane between the level crossing (now the footbridge) and the approach to the Lock.

The outcome of this period of activity in the thirties was that the whole of the development of the river front from Romney Lock to the Western Railway Bridge was completed before the outbreak of the War in 1939.

This was not, however, the end of the story. The Council again nearly decided to let Romney Walk go when the 1947 floods caused serious subsidence and the Walk had to be closed. When the question of its restoration came up the Council was disinclined to spend the money. A Minute of March 1951 says: ‘Romney Walk is a comparatively unimportant part of the riverside, but it is apparently a public highway which the Council is obliged to maintain and it would be difficult to make out a case for stopping it up’. Eventually additional land was acquired from British Rail and the work of restoration went ahead, but it was not until July 1954 that Romney Walk was re-opened.

Thames Side

Again, after a period of neglect in the 1970s and 1980s, the condition of the Walk deteriorated. In recent months Windsor Heritage has mainly by voluntary effort repaired and landscaped the area, clearing and planting up the river banks, replacing and repainting the railings, clearing accumulated rubbish and creating a small grassed area with seats. Windsor Heritage deserves praise for its initiative and the work carried through with the help and encouragement of many individuals and organisations.

Clewer Mead

At the opposite end of the riverfront a series of controversies marked the post-war period. Some little distance to the west of the railway viaduct was Clewer Mead, the former Etonian Country Club. This had been requisitioned during the war, and in 1946 the Council took the opportunity to purchase it. The land between the railway viaduct and Clewer Mead was already in the Council’s hands. This meant that an extensive new area of the riverfront had come into public ownership. The question was what to do with it. The question was partly answered by the provision of a miniature golf course on the site of the former stoneyard and the laying out of flower beds and lawns. Clewer Mead itself, however, remained derelict; the story of the post-war years is a saga of projects proposed and projects abandoned.

The Leisure Pool

In 1953 a Development Company offered to take over the whole of the riverfront from Deadwater Eyot westward to Clewer Mead and make it into a Pleasure Gardens area, complete with a small zoo, a beer garden and a variety of amusements. In the early stages a majority of the Council favoured the project, hoping that it would produce revenue to relieve the rates. But the town was divided in its reaction. Town meetings, petitions a public enquiry followed and the proposals were defeated. Later plans by Associated Pleasure Gardens Ltd in 1969 met with the same fate. the prevailing opinion appeared to be: keep the riverside quiet and genteel or if not quiet at least do not encourage noise and rowdyism.

Clewer Mead was demolished in the sixties and for some years the area was used as a coach park. Eventually the site was used for the present highly praised Leisure Pool. It took forty years to attain this solution. The story of the Windsor Baths is a separate story — a story within a story. The old open air baths on either side of the viaduct had been condemned on public health grounds in 1938. Then, after a long interval, came the open War Memorial Swimming Bath. Never more than moderately successful it was eventually abandoned and so the way was open for the planning of a new covered-in swimming pool, with high standards in the provision of facilities. So after much heartsearching and controversy the problem of what to do with the Clewer Mead site has been solved, hopefully for a long time to come.

A small but important step was taken soon after the opening of the fine new Relief Road Bridge in 1966 — a fitting termination visually to the end of Windsor’s riverfront. In the following year the riverside walk was continued along the frontage of Clewer Mead, with a path by the bridge to Barry Avenue. It was now possible to walk by the Thames all the way from the Victoria Bridge on the Datchet Road to the New Elizabeth Bridge.

The Bridge

An unexpected addition to the amenities of the riverside came in 1970 with the closing of Windsor Bridge. There had been fears for the safety of the bridge for many years, but despite weight restrictions the volume of traffic continued to increase and the narrow canyon of Eton High Street, the overladen bridge and the main streets of Windsor had to submit to a seemingly endless succession of vehicles and to the noise and pollution which they generated. Nevertheless, when the Berkshire County Council, now the responsible authority, took the final decision to close the bridge there was consternation. It seemed unthinkable that the historic link between Windsor and Eton which the bridge had represented for so many years should be terminated.

Schemes for a ‘bailey bridge’ as a temporary means of keeping the bridge open and projects for the building of a new bridge (or re-building the old one) were urgently discussed. Gradually, however, public opinion swung round to the point of view that the closure of the bridge, far from being a disaster, could bring positive good. It was fortunate that the Elizabeth Bridge, the new Windsor and Eton Relief Road, had been opened four years before. The Windsor Bridge itself and the Windsor approach have been attractively pedestrianised. The Castle towers up to the south and the views, downstream to Romney Island and upstream to the promenade and the islands, open up new vistas.

The Islands

The main stream of the river has several islands which add attraction to Windsor’s riverside. Each has a history of its own. Downstream is Romney Island — half-a-mile in length and almost divided into two islands, Upper Romney and Lower Romney. For centuries the towpath followed the length of the island; a View of the Castle by Leonard Knyff (c.1708) shows the island almost devoid of trees, with five horses towing a barge upstream. The towpath crossed from Windsor bank and then back again at the other end, the horses having to swim both ways. Romney Island was very close to the Windsor bank, a fact which made the channel on that side the obvious place for the construction of Romney Lock at the end of the eighteenth century.

Fireworks Eyot

The promoters of one of the railway projects in the mid-nineteenth century, opposed both by the Crown and the College, tried to use Romney Island for a route between the two, only to find that Eton College had purchased the island from the Thames Navigation Commissioners. Romney Island is still owned by Eton College, although within the boundaries of the former Borough of Windsor. Today Romney Island remains ‘undeveloped’, with some fine views to Eton College Chapel in one direction and the Castle in the other.

Just above the bridge is Fireworks Eyot, in times past ‘much used for pleasure boats and fireworks’. So wrote R. R. Tighe, the Windsor historian, in 1847. He went on to talk about the value of ‘improving and preserving the little island which, without some small protection, will soon be carried away’. The eyot was then in the occupation of Eton College and remained so until in 1937 the Council took the decision to terminate the tenancy and take the eyot into its own control.

The survivial of Fireworks Eyot, however, was always precarious. Serious erosion was reported in 1966 and the Council almost decided to let it go. But it had to change its mind when it became clear that, if it persisted in this decision, it was under a legal obligation to eliminate the eyot so completely that it would not be a hazard to navigation. This, it proved, could cost the Council considerably more than the measures necessary for its preservation. Public opinion too had been aroused in defence of the eyot and so the island eventually remained, a haven for wildlife and a focal point in the riverscape.

Higher up is Deadwater Eyot, with the adjoining Baths Island, continuing the string of islands below and above the Railway Bridge. This, except for the part occupied by the Windsor Swimming Club, is open to the public. The grass is mown and it has some fine trees, but proposals to ‘develop’ it have been resisted. At the downstream tip is one of the world famous views of the Castle, rising high above the river in all its majesty. One of the curious facts about Deadwater Eyot is that for centuries it was in Buckinghamshire not Berkshire. The local government reorganisation of 1974, bringing Eton into Berkshire, ended what seemed an historical anomaly, arising perhaps from some quirk of land ownership in the past.

Thamesmead

The final riverside acquisition came in 1974 — the very last year of the Windsor Council. Since the end of the Second World War, Windsor had expanded to the west and it soon became a cause for concern that the thousands of new residents had no direct access to the riverside. The existing access to the central riverside areas and to the Home Park beyond was not a satisfactory answer to the need. Opposite the new estates at the western end of the town was the large area of meadow land bordering the Mill Stream and the main river between Sutherland Grange and Levertons — away to the west of the racecourse.

Its acquisition was first proposed at least as early as 1960. When the Council took the matter up in earnest several years later, a long-drawn out battle took place with the owners who wanted to maintain at least a partial hold. The Council had eventually to resort to a Compulsory Purchase Order. The Town Clerk was able finally in February 1974 to report to the Council that the Minister had unreservedly confirmed the Order and so another open space passed into public ownership.

Apart from necessary maintenance, the area has been left without development — those who want amusements, organised recreation, refreshments must look elsewhere.

It is significant perhaps that just as the Home Park was at the extreme eastern end of Windsor so ‘Thamesmead’ — an appropriate name but not one universally adopted — should be at the extreme western end of the extended town.

Raymond South