Published in Windlesora 17 (1999)

© WLHG

This is a history magazine, so whatever happened it was presumably some time ago.

Of course: it was on 17 March 1883. St Patrick’s Day—note that!

And Lady Florence? Who was she?

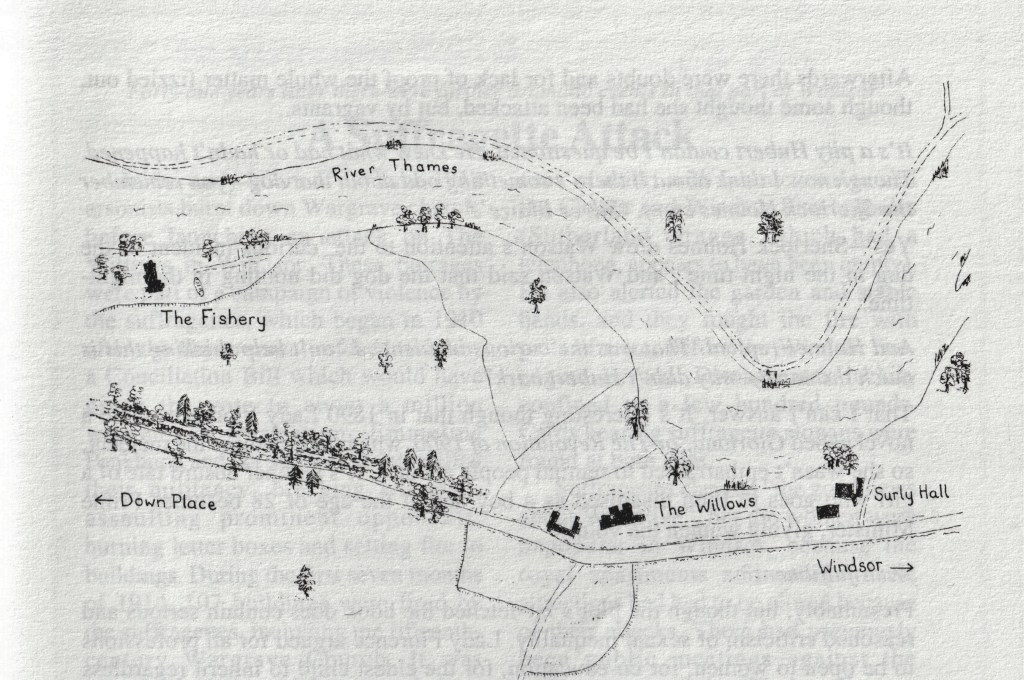

Lady Florence Dixie, married to Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie, known as Sir ABCD. They had two sons and lived at The Fishery, a Regency house in meadow-land by the Thames, on the road from Windsor to Maidenhead. She was 25 years old at the time of the attack, but I think I’d better tell you a bit more about her first. Lady Florence was born a Douglas, youngest daughter of the seventh Marquis of Queensberry, and her oldest brother was the next Marquis who brought the Queensberry Rules into boxing—

You mean the infamous man who got Oscar Wilde sent to Reading Gaol for being gay’?

Well, it was Oscar who sued the Marquis unsuccessfully for libelling him as a homosexual, but yes, Lady Florence was aunt of Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas. But that was twelve years later and she’d established herself as quite a character in her own right long before that. As a girl she’d wanted to do whatever her brothers did and she became a skilled sportswoman—good swimmer, brilliant horsewoman and fine shot. A very adventurous young lady in fact, and when she was only 21 she organised an expedition to the wilds of Patagonia with her husband and twin brother. She wrote a book about how they explored, hunted, and lived off what they killed: if you want to know about the tastiest bits of guanaco, the delights of ostrich liver kebabs or crunchy chorlito, read Lady Florence.

Ugh!

She used to say that she had killed lions in Africa, stalked gazelles in Arabia, and bears in the Rocky Mountains. Later on however, after the event we’re coming to, she wrote books against hunting. Perhaps she’d learnt that it isn’t much fun being the one hunted. But she was always passionate about animals, bringing home a jaguar from South America as a pet. She christened it Affums and when H.G. Wells was a boy visiting his uncle at Surly Hall, the inn nearby, he used to be in terror of it leaping out at him. But eventually Affums was packed off to a zoo.

On her next expedition, to South Africa, Lady Florence acted as correspondent of the Morning Post for the Boer War of 1880-81. She was the first woman war correspondent, which was appropriate for a woman who campaigned for sexual equality. She also dabbled in Irish politics, which may have got her into trouble in 1883.

Wasn’t that the time of Gladstone and Irish Home Rule?

The First Home Rule Bill was a year later, in 1884. But there was a great deal of trouble, particularly over the way English landlords evicted small Irish tenant farmers, often very unjustly and without compensation. There was much resentment and a protest organisation called the Irish Land League was set up which became involved in terrorism. There had been a number of outrages, including the murder in Phoenix Park in Dublin the previous year of Thomas Burke and Lord Frederick Cavendish, two English officials. Lady Florence had raised £6,000 to help dispossessed peasants and she supported Home Rule, but she accused the Land League of misappropriating funds donated for relief of poverty. She’d written a couple of letters to The Times about it just before the attack. The attempt on Lady Florence’s life therefore may have been the terrorists’ answer. Certainly she claimed to have received death threats.

So just what did happen?

Well, according to Lady Florence, it was Saturday evening and she was standing outside The Fishery with Hubert, her St Bernard, just before 5 o’clock, watching a handsome soldier go by with his girl-friend. Just after that two women came up to her and asked what the time was. She told them, and then passed through a wicket-gate into a narrow plantation of trees running parallel to the road. But then she realised they were following her. At the 4-barred fence which divided The Fishery from The Willows she turned to face her pursuers and saw that they were not women at all.

She was seized by the neck and flung to the ground by one man, while the other drew a dagger from under his cloak. She saw a flash of steel as he struck at her. The knife passed through her dress but the blade was deflected by the steel of her corset and only scratched her skin. As he tried to strike again she grabbed the blade with her gloved hands and was cut on the palms. She cried out ‘Beau! Help!” twice, before one of the villains stuffed earth in her mouth, and knocked her on the head. ‘It was a fearful moment,” her Ladyship told reporters later, ‘and I struggled hard.” She fainted, but not before she saw Hubert the dog come to the rescue, pulling away the man with the knife. ‘I owe my life to the St Bernard dog,” she said.

The next thing we know is that she was found, muddy and dishevelled, by the dog-keeper, who rushed into the house for Sir Beaumont. She came in dazed, with her hands bloody and her blue serge dress slashed by the knife. Sir Beaumont wanted to call a doctor, but she wouldn’t let him, so he left her to lie down and went off quickly to the police at Windsor.

Did they catch the villains?

No, though they mounted a watch on Windsor, Maidenhead and Reading stations.

Did they know what they were looking for?

Not really. Lady Florence couldn’t describe her attackers clearly. There were wild rumours in Windsor that one was wearing a green dress—to show Irish allegiance—with a tale of an unknown woman in a green dress in William Street the day before—

That’s not convincing evidence!

Of course not, but Windsor was buzzing with the event and everyone tried to remember something to help. Lady Florence said only that they were very dark in complexion and clean-shaven. Both wore cloaks, one had a bonnet with a veil and the other a ‘wide-awake’ hat. She denied reports that they had Irish accents.

What about witnesses? What about that soldier and his girl?

Well, the press couldn’t get to the soldier but they found the young woman, Sophia Harding. She came from South Place, one of the worst slums in Windsor, behind Clarence Crescent—where Ward Royal is now. She said that she’d been walking towards Maidenhead with the soldier until it came on to rain. Then because he’d got his best tunic on he wanted to get back to barracks. They turned and on the way back saw Lady Florence with two dogs, whistling to one of them…

Two dogs?

That’s what Sophia said. Perhaps the one whistled to ran off. Anyway they went on along the road and passed a woman carrying a large basket as if going to market. Sophia noticed that she had very large feet.

But only one woman. Whatever the size of her feet, she can’t have been involved.

I suppose an accomplice might have been hiding in the trees. No bonnet or wide-awake hat though.

Anyone else see anything? It must have been a busy road.

Not as busy as today, of course, though the bit of road we’re concerned with is bypassed now. There were carts, and some were inclined to see a phaeton which bowled along around that time as the get-away vehicle. Sir Beaumont’s page, William Parkinson, was coming back from Windsor and just past Clewer Park he claimed to have seen ‘two strange-looking women’, with a soldier and a girl a hundred yards behind.

What was ‘strange’ about them?

He didn’t say. One had a dark green dress on if it matters. Then there was Frederick Rowe, butler to Colonel Harford of Down Place. He was on the road coming from Windsor with his dog and looking back at it, especially when the Surly Hall dog—yet another dog—joined his and he thought they might fight. Suddenly he saw two ‘individuals’ behind him who hadn’t been there before. He thought they must have come out of the stable gate of The Willows. He said they looked like women, but exceptionally large, and one was wearing a cloak. Then he reached Down Place and saw them no more.

I suppose they might have been the attackers. What about clues where it happened? There must have been signs of a struggle? The knife?

Very little. No knife was found. There were men’s footprints, but then they might have been made by anybody walking through. There was no real sign of Lady Florence having been thrown down and struggling for her life.

Odd.

Sir Beaumont argued that was because his wife was very light in weight. I ought to tell you about the gardener though—not Sir Beaumont’s, but Captain Brocklehurst’s, the owner of The Willows. At that time his gardener was potting flowers outside his greenhouse, and at a spot where he says he frequently overheard Sir Beaumont and his wife chatting on the other side of the fence. Yet he heard nothing.

Not the cries for help?

Nothing. But Lady Florence pointed out that she only called out twice, and the gardener might have been out of earshot, whatever he said.

So there isn’t any actual evidence of the attack apart from what Lady Florence said. And her injuries, of course.

Self-inflicted. And the slash in her dress. I’m beginning to think her house, The Fishery, was well-named. It’s a very fishy business, though if it was staged I can’t see why. She could have wanted to blacken the Land League further. Remember her letters? And there’d been an explosion in Westminster a couple of nights before which was blamed on the League. However the affair certainly caused a sensation at the time and everyone believed an outrage had been committed. Queen Victoria sent John Brown down to enquire, the Prince of Wales and all sorts of people in

high places sent messages of sympathy, and the national press got very excited.

Afterwards there were doubts and for lack of proof the whole matter fizzled out, though some thought she had been attacked, but by vagrants.. It’s a pity Hubert couldn’t be questioned. He knew what had or hadn’t happened.

Though now I think about it there’s something odd about that dog—you remember the Sherlock Holmes story, ‘Silver Blaize’?

Yes—Sherlock Holmes drew Watson’s attention to the ‘curious incident of the dog in the night-time’, and Watson said that the dog did nothing in the night-time.

And Holmes replied ‘That was the curious incident’. I can’t help thinking this is much the same—why didn’t Hubert bark?

That I can’t answer. It’s interesting though that in 1890 Lady Florence wrote a novel called Gloriana; or The Revolution of 1900 which fictionalises the incident, so she wasn’t embarrassed to remind people about it. It’s a rather absurd tale of a girl who goes to Eton disguised as a boy and at the age of 28 becomes Prime Minister, giving women the vote—

Wish-fulfilment?

Presumably, but though the plot’s far-fetched the book does contain serious and reasoned criticism of sexual inequality. Lady Florence argued for all professions to be open to women, for co-education, for the eldest child to inherit regardless of sex, even for a women’s army! The novel ends, by the way, with a view of England in 1999, from a balloon. It’s a land of peace and plenty with all injustices of sex and wealth done away with.

Some hopes! But I’m warming to Lady Florence, she’d obviously got guts.

She was ahead of her time perhaps. When she died in 1905 The Times described her as having an ‘attractive and attaching personality’ despite her ‘somewhat peculiar views’.

It would have been a man who wrote that.

Hester Davenport

References:

Dixie, Lady Florence, Across Patagonia, Richard Bentley & Son, 1880

– In the Land of Misfortune, Richard Bentley & Son, 1882

– Gloriana; or The Revolution of 1900, Henry & Co., 1890

Dictionary of National Biography, entry for Lady Florence Dixie

Roberts, Brian, The Mad Bad Line The Family of Lord Alfred Douglas, Hamish Hamilton, 1981

Robinson, Jane, Wayward Women: A Guide to Women Travellers, Oxford University Press, 1990

The Times, 8, 14, 19 March 1883 and 8 November 1905

Vanity Fair, edition for 1884

Wells, H. G., Experiment in Autobiography, 1934

Windsor Express, 23 March 1883.