Published in Windlesora 33 (2016)

© WLHG 2018

Educating the children of the poor had been in the past looked upon as a rather risky undertaking. There was a strong belief that it was dangerous to educate the masses, in case they should rise above their station.

Windsor had just one school for the poorer children of the town, which was the Royal Free School endowed in 1706 for 40 boys and 30 girls. During the early nineteenth century, opinions began to change. It was seen as important to provide some basic education for all poor children. It became a matter of pride for a town to teach these children the words of the scriptures.

By 1830, there were 3 charity schools in Windsor and Clewer, and two small church schools which, between them, taught about 500 children. However, there were an estimated 1,200 children under the age of 15 in Windsor at the time, discounting the 3-400 children of soldiers who regularly moved in and out of the two Windsor barracks, although some of these were educated in army schools. And there were also the Sunday Schools, educating about 300 children by the middle of the century.

Although they all were charity schools, and we talk about the children of the poor who were educated there, they were in fact carefully selected children of respectable working families, that is those where parents were married and were members of the respective Church. No ragamuffins, street urchins, pauper children or ‘God forbid’ illegitimate children, would be admitted. Furthermore, these free schools were not entirely free, children had to bring a weekly penny to school for the penny bank, and ‘the parents being desired to send their children cleanly washed and with decent shoes and stockings’.

These new schools therefore, except perhaps the workhouse school, still did not offer schooling for the poorest and most destitute, the ragged children of Windsor. There was one school that did however, and which by the middle of the century had attracted important patronage.

Ragged Schools came into being early in the nineteenth century and dedicated themselves to the education of destitute children. Dickens wrote in a letter that the Ragged Schools were started in the early part of the century by a shoemaker of Southampton and a chimney sweep of Windsor. The Southampton shoemaker has been identified as John Pounds, who started teaching poor and destitute children without charging any fee, but it has never been established who the Windsor chimney sweep was. The earliest reference we have to this school is from 1845 when the Rev. James Barker, a Congregational minister, applied to the Windsor magistrates for a licence to preach in the Ragged School in George Street, a school which was already well established. An article in the Ragged School magazine of 1869 throws further light on the story – or rather adds to the confusion. It reads:

In the Royal Borough of Windsor a ragged school was planted about 24 years ago and though with a chequered career it had done much to socialise and to save the children of want. But who had the honour of founding it? This honour is divided between a city missionary and a chimney sweep.

According to this, the school was established in 1845, but there are earlier references to a school in George Street. Charles Knight Jnr. mentioned the ‘sweeps school’ in the 1820s, when he was overseer of the poor, and of course, there are Dickens’ letters. But official records of this school only go back to the time that Lord Shaftesbury formed the Ragged School Union in 1844, and the Rev. James Barker got involved with the Windsor Ragged School. The name of the chimney sweep has unfortunately been lost. He is only ever referred to as ‘the poor chimney sweep‘.

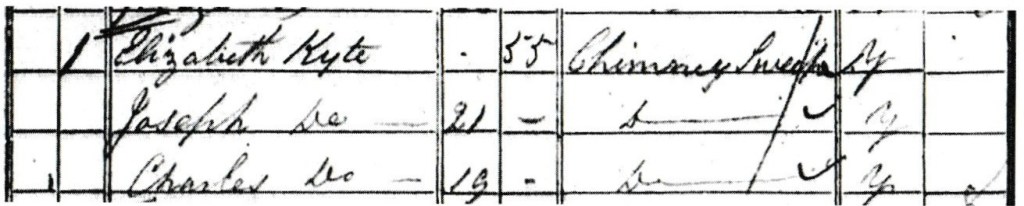

The 1841 census shows that there were nine chimney sweeps resident in George Street, three of these are possible candidates.

James Hasting was 50 in 1841.

Elizabeth Kyte was 55 and had two grown-up sons in the business, but all of them were still listed as sweeps in the 1851 census.

Thus the strongest contender is one Thomas Millerd. He was 70 year old in 1841 and had a 35-year-old daughter who could well have been an assistant or teacher. Furthermore, he also owned a shed or stable in the street, which could have been a schoolroom, and the railway paid him £5 compensation for his shed. He also had a number of young boy sweeps living with him, and it is feasible to assume that they were not only his apprentices but also his pupils.

George Street was one of the meanest streets in Windsor. Charles Knight wrote in his recollections:

‘There was a whole street of a vicious population where almost every house was a den of infamy. At the bottom of this foul quarter stood our gaol.’

In 1849, George Street was demolished to give way to the new railway station, therefore in 1847 the ragged school had to move to nearby Goswell Lane. The school received £15 compensation from the South Western Railway. Their new home was a coal shed with an earth floor and it was said that ‘the scholars were about as dingy as the place of meeting‘.

In March 1847, the Windsor and Eton Express reported:

‘more than 100 young persons, formerly neglected, may be found daily reading the scriptures and listening to religious instruction in the school room in Goswell Lane; occasional supplies of clothes to the destitute children reflects the honour of a well-directed charity.’

The children also received food and clothes, and vocational training. Food, clothes and shelter were probably the main attractions for the children who attended these schools. Most interesting is that the schoolmaster was said to be assisted by soldiers from the Cavalry barracks. The Ragged School magazine reported:

‘At Windsor, there is a Ragged School conducted by a poor chimney sweep, where the visitors lately found in a sort of shed with an earth floor, there were gathered about 100 young persons. He was aided by some privates of the Life Guards, who did much to make the school remarkable for its discipline.’

The fact that soldiers helped to teach in the Ragged School is interesting and indicates that there was a military interest in this school. Perhaps neglected army children, whose parents lived out of barracks and had therefore no access to the army schools, regularly attended it. The soldiers certainly must have installed some military discipline into what was probably a very unruly bunch.

In 1850, the school moved again, to Clewer Lane (now Oxford Road) near Clarence Crescent, but no one knows exactly where. There is one reference to this place in the Windsor and Eton Express, which reported, ‘It is commodious, convenient and well lighted, and has been erected by voluntary contributions‘. There were now 150 pupils, but the poor chimney sweep is no longer in the picture. The school was now run by Mr and Mrs Norman. Frequent reports in the Windsor and Eton Express point to an increasing interest in the Ragged School. There was no shortage of subscribers and benefactors to help these children, who 50 years earlier were not deemed worthy of any charity.

The pupils soon outgrew the building in Clewer Lane and, in 1852, a subscription list for a new daily Ragged School was set up. It was Mr James Bedborough, local builder and twice mayor of Windsor, who gave the site for the Ragged School in October 1853. The new building was to be sited at the western end of Clewer Lane (now Oxford Road) and is the only one found on a Windsor map of the period. This building still exists today, and unlike many of our other nineteenth-century school-houses, which have become desirable domestic properties, it is still used as a nursery.

The subscription list published in the paper included officers and men of both regiments stationed in Windsor. Again, we see that there was a strong military interest in the school. The Windsor newspaper also emphasised how much such a school was needed in this area. In May 1854, the school was opened with 40 boys and 37 girls. There were also parenting evenings and lectures for the poorer classes.

The problem of providing education to the poorest children, however, remained; a meeting of the Windsor and Eton Ragged Schools in 1856 reported that,

‘… a number of boys and girls are loitering in our lanes and streets, their parents are utterly heedless of their mental and moral welfare, they are never sent to any of the excellent day schools. Most youths are so corrupted by the bad example of their parents as hitherto to have defied the varied efforts that have been made to win them.’

In 1863, the Clewer Sisters also took an interest in the poor children of Clewer and were said to have started a ragged school in Clewer Fields with 7 children; they taught them in one bare room in a cottage. The sisters wrote about their pupils: ‘It was difficult to tell the difference between the boys and girls as they were equally ragged, equally barefooted, equally shock-headed and used the same bad language‘.

Out of this grew the mission of St Stephens. It is not known, however, if the two Ragged Schools, just a few yards apart, worked together or functioned side by side, what we do know is that the schools set up by the Clewer Sisters in this part of Clewer soon became fashionable fee paying schools and their Ragged School did not last long.

In 1877, the Windsor and Eton Ragged School in Oxford Road was run by Miss Caroline Alexander; it had a further 14 voluntary teachers. There were 60 Sunday attendances, 40 in a mixed infant class, 17 industrial girls and 24 boys; 12 mothers attended parents’ meetings on Mondays, there was a penny bank of 200 adult depositors and a clothing club. It was, however, the end of the Ragged Schools, 320 of which had been set up around the country, and whose interests were guarded by the Shaftsbury Society. It was the Education Acts of the 1870s, which for the first time guaranteed free education to all children, and the Act of 1880, which made education to the age of 10 compulsory for all, that made Ragged Schools obsolete. The school building was sold to the Clewer sisters.