Published in Windlesora 25 (2009)

© WLHG

Some of the objects in the Windsor & Royal Borough Museum hint at a connection between the business and livelihood of a Windsor retailer in the early twentieth century, and an Atlantic-wide traffic in humans and goods, established in the seventeenth century, which was to generate much of the wealth that laid the foundations of the British Empire.

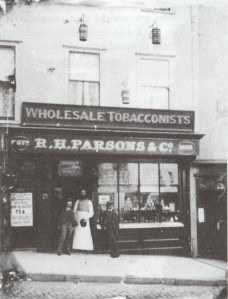

A photograph donated in 1990 and taken, we are told, by the donor in 1912, shows a smartly-dressed shopkeeper, hat in hand, wearing a spotless white apron reaching almost to his ankles, standing in front of the neatly-presented shop front of 12 Thames Street. Either side of him stand two young boys, presumably his sons. Above their heads, the signboard reads in bold letters: R. H. Parsons & Co est. 1800, and above that Wholesale Tobacconists.

In 1966, the Museum acquired four wooden carvings which had been attached to the front of the same shop and can be seen in the photograph.

These are symbols of the shop’s merchandise and comprise two out of the three cylindrical shaped objects, which appear in the picture hanging on the front of the shop above the name board, and two black wooden figures which can only be made out dimly in the photograph as hanging either side of the door of the shop.

The two carved figures, 2 feet 6 inches (76cm) and 2 feet 11 inches (89cm) high, represent we are informed in the note with the accession, a black boy or Guinea boy, and a kilted highlander. The boy, supposedly a native of Guinea (as West Africa was known in the early days of the Atlantic slave trade), wears a kilt and headdress of tobacco leaves and carries a plug of tobacco under his left arm. The highlander wears a plumed headdress and holds a horn of snuff. Both figures still bear the brackets which had once attached them to the shopfront on either side of the door.

The Guinea boy may represent a plantation worker or slave, or a descendant of a slave, transported from Africa. The kilted Scotsman may simply represent a smoker. I am told that in Canada and the United states it is common for a carved figure of a North America Indian, representing a smoker of tobacco, to stand outside tobacconists, as one now does outside the Havana House around the corner from Thames Street in the Windsor and Eton Central Station shopping mall.(1) However, one wonders whether the kilted Scotsman may also have represented a plantation owner or manager – not merely the consumer of tobacco, but the overseer of its production.

If so, our figures thus represent two inextricably but antagonistically linked participants in the production process: the one, who grew and harvested the tobacco, forcefully transported from Africa, the other who oversaw and drove on the former, possibly under the threat of the whip and gallows.

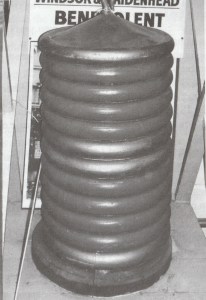

The wooden cylinders are approximately 2 feet 6 inches (76cm) high and 9 to 12 inches (23-30cm) in diameter. They performed the same function for the tobacconist shops, as did the glass-faced cylinders bearing red and white spiral stripes that hung outside barbers. They consist of horizontal reeds or ropes wound round the cylinder representing, we are informed in a note with the accession, a tobacco roll, and indicating that the strong-flavoured rope tobacco was on sale in the shop. This would have been in plugs for pipe-smoking, and the shop would have had pipes and tobacco pouches for sale too, though by the time the photograph was taken cigarettes would have been the dominant form in which tobacco was sold.

Tobacco production was, of course, of no value unless the producers had access to a mass market in which they could sell their merchandise. In this respect, of crucial significance for this vast industry, which straddled the Atlantic and linked three continents, were the thousands of tobacconists who delivered the product to the consumer, thus facilitating the extraction of profit from its production. The tobacconist in Thames Street would have played a modest, but significant, part in this process.

A deed in the archives of Eton College shows that, in 1639, number 12 Thames Street was acquired on behalf of the Eton Poor Estates, together with the adjoining property, number 11, for three score and ten pounds, from money bequeathed by fellows of Eton College to be spent on the poor in the Parish. Number 12 had become a tobacconist by 1833 at least, as in this year a lease was granted to ‘William Henry Burge of New Windsor, tobacconist’. He was succeeded by three more tobacconists, the last of whom held a lease which was supported by guarantors named as ‘Messrs Charles Lambert and Charles Butler of the County of Middlesex, tobacco manufacturers’, presumably the founders of the present day cigarette manufacturer (the first cigarette factory in England opened in 1856, cigarette-smoking having been popularised by soldiers returning from the Crimean War).

In 1876, when Lambert and Butler entered directly into a seven years lease for the premises, their tenant was named as Richard Hussey Parsons – the name that appears on the shop’s signboard in the photograph. This lease was signed, not only by Charles Lambert and Charles Butler, but also by Charles Edward Lambert and Charles Butler junior, presumably their sons, thus indicating a business partnership comprising the two fathers and their two sons -all four named Charles! In 1882, Lambert and Butler entered into a new seven-year lease for the same premises, now described as ‘in the terme or occupation of Richard Hussey Parsons’.

By this time, therefore, the Parsons, as tenants of Lambert and Butler, were firmly established in the premises where they were to remain for nearly another forty years.

In 1897 a lease was entered into directly with Lewin George Parsons for premises lately in the occupation of Richard Hussey Parsons but now of the said lessee and his undertennant’. It seems likely that Richard Hussey was the father, and it is Lewin George, his son, whom we see as the shopkeeper in the photograph. We can also note that the Parsons business had by now broken free of its 20-year association with Lambert and Butler.

But Lewin George Parsons did not serve the full term of a 14-year lease entered into in 1909 since, although the 1916 Kelly’s directory records Parsons and Son as the proprietors, from 1920 other names appear on the lease and in the directories. So ended a relationship of some 40 years between the Parsons family-run business and the premises at 12 Thames Street. The Parsons were succeeded by three other tobacconists until, in 1966, the Trustees sold the property. At the same time they decided to dispose of some its more historic contents: to sell the old tobacco barrels for £10 each and loan the antique tobacco twist and the figure to the Guildhall Exhibition, from where these exhibits found their way to the Museum’s permanent collection. The sale of the property was completed on 1 March 1968, the details being recorded on the original document of 1639 which had executed the conveyance of the property to the Trust 329 years previously, thus bringing to an end over 135 years of the sale of tobacco at 12 Thames Street. (Two years later, the Trustees sold 11 Thames Street. The purchaser of both properties was Landlink Properties Ltd who, no doubt, were instrumental in the development that was to take place shortly afterwards.)

Mr. Parsons and his son should have been well placed to do a brisk business in their location on Thames Street. But he, and other tobacconists trading from the same premises before and after, would have faced competition from several others in central Windsor. The directories show that between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, number 12 was seldom the only tobacconist in Thames Street and, on occasions there were no less than five tobacconists in Peascod Street alone, though few of these demonstrated the continuity of trade from the same premises as was the case at 12 Thames Street. (By 1960, in a possibly unwelcome development for the proprietor of Number 12, another tobacconist, the House of Bewlay, had established itself as a very close neighbour at 7/8 Thames Street, only four doors higher up the street, and was to remain there until at least 1974.)

It also appears that, from as early as 1833, number 12 had accommodated two separate retailers, although it is clear that the unit trading as a tobacconist was the superior of the two and, from the later years of the Parsons’ tenure, their business may have benefited from the fact that their co-occupant was a confectioner. By 1940, that important mid twentieth century British institution, the Aerated Bread Co (ABC) had established itself next door to the tobacconists at numbers 13 and 14 and was to remain there until at least 1974 when the directories cease. The popular teashop was possibly a welcome neighbour for the tobacconists, its customers sometimes dropping in to buy cigarettes before going for their cup of tea next door.

What has become of the property since the photograph taken in 1912?. Looking from across the street with our backs to the Castle, we can trace the higgledy-piggledy line of the roofs descending, like one side of a rickety spiral staircase, as it follows the downward curve of Thames Street (steepening just below number 12) around the Curfew Tower. Below the roofline, we can see the upper two floors of the property remaining virtually unchanged. Even the metal bolts in the wall, which would have held the tobacco rolls, remain. However, although the roof and upper floors may have changed little, when compared to the photograph, the ground floor is now unrecognisable.

Shortly after the sale of the property in 1968, an opening was made through the middle of the ground floor into what was to become Curfew Yard. The effect of this was that number 12 now contained two shops, separated from one another by the new passageway. These have since accommodated an assortment of traders, none of which, however, have sold tobacco. The most recent occupant of the left hand unit was Ben and Jerry’s ice cream parlour (now relocated to the top of Peascod Street). The right hand unit is now occupied by Nambu-tei, a Japanese Restaurant, whose signboard, advertising the restaurant as ‘Sushi’, appears to be attached to the same bracket that once bore the lower of the three tobacco rolls shown in the photograph.

Now let us consider the source of the tobacco on sale at 12 Thames Street.

In 1639, when the Trust acquired the property, the first African slaves were beginning to arrive in the tobacco colonies of Virginia and Maryland, as the supply of white indentured labourers there declined.(2) The slaves were brought in British ships either directly, or via the Caribbean, from Guinea, which was the term then used to refer to West Africa.(3)

At around this time, following what the British colonists described as the ‘expulsions of the Salvages [sic] to gaine the free range of our countrey…’ and [after] the ‘winning of the Forrest’ by the colonists, hundreds of thousands of acres were brought into use for tobacco cultivation.(4) The consequences were dramatic, the output of tobacco from the colonies increasing from 60,000 pounds (weight) in 1620 to 15 million pounds by the 1660s, and 28 million pounds by the mid 1680s. The consumption of this enormous volume of produce was, however, dependent on the creation of a mass market in the home country which, in turn, was only possible due to the

widespread appeal of tobacco in England and the fact that “by the carly 1630s it was sold the length and breath of the country.”(5) By 1614, 7,000 shops sold tobacco in the country.(6)

For Europeans, the whole system provided many benefits: for the merchants and plantation owners, financial gain in the form of (sometimes huge) profits; for the retailers, a means of livelihood; for the smoker, the stimulating or soothing effects of the mild narcotic and, in some cases, no doubt, an aid to stylish deportment or a relaxed social manner. For non-Europeans, though, the very existence of this new industry depended on wide scale suffering in what amounted to something of a holocaust for large sections of the indigenous populations of two continents: in one case through the dispossession and destruction of their lands, and in the other, in the form of their enslavement and enforced transportation from their homes to an unknown destination across the ocean. (Before the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, over six million slaves were shipped from Africa, nearly half of whom were carried in British ships. Over 10 per cent of these perished at sea.(7)

This booming transatlantic trade therefore depended on the tobacconist shop at one end of the process and, at the other end, on the labour of the Guinea boy. The accessions in Windsor Museum enable us to catch a glimpse of each end of this process. Mr Parsons was only one small cog in this machine which had been operating for over two centuries by the time he opened his shop in Thames Street. In the photograph, we see him, in his clean white apron, as the respectable face of the process, as viewed by British consumer located at the apex of the triangle of commerce between humans, crops and cash. In the carving of the Guinea boy, if we look beyond the theatrical, almost comic, attire, and his assumed air of gaiety, we are reminded of the conditions suffered by the real person, playing his unwilling part in the process too: the slave working in the malarial fields of Virginia.

Gwil Colenso

- Personal communication from the proprietor of Havana House.

- James Horn, Tobacco Colonies: The Shaping of English Society in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake in Nicholas Canny (ed.); The Oxford History of the British Empire (OHBE) Vol. I The Origins of Empire, p179.

- PEH Hair and Robin Law, The English in Western Africa to 1700 in Nicholas Canny(ed.) OHBE Vol. | The Origins of Empire, p241.

- James Horn, op cit, pp175-6.

- ibid, p183.

- British Empire magazine, No 5, 1979.

- David Richardson, The British Empire and the Atlantic Slave Trade 1660-1807 in P.J. Marshall (ed.) OHBE Vol. Il The Eighteenth Century, pp 441, 454.

The recent photographs were taken by the author.