Published in Windlesora 25 (2009)

© WLHG

A curious entry in the notebook of Windsor cutler, George Pridie, in May 1830, reads: ‘A Drummer Belonging to the first Regiment of Foot Guards was flogged on Tuesday Died on Wednesday and Buried on Friday’.(1) Where did Pridie get his information from, was it local gossip or rumour filtered through from the barracks in Sheet Street? Perhaps he read it in the Weekly Dispatch which reported on 16 May 1830:

“…. the horror of the occurrence will supply its own comment. On Thursday last a Drummer of the 1st Battalion of the 1st Regiment of Foot Guards [Grenadier Guards] stationed at Windsor underwent the punishment of flogging and was this day buried.(2)

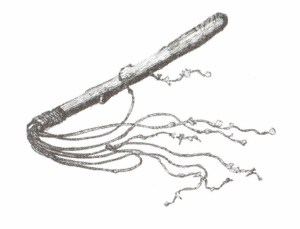

At this time flogging was still the main punishment in the British army. A man could be given up to 500 lashes for being drunk, for going awol, for insubordination, or disgraceful conduct, so it is surprising that only a few soldiers died afterwards, but many were maimed for life, with deep lacerations to their backs, even internal injuries. It was also a time when flogging in the army was hotly debated not only in the press, but also in Parliament. During the French wars reports on military punishments, when a soldier could be given up to 1,000 lashes, had been suppressed. Now the public was eager for sensational news about flogging, but the army which maintained that flogging was necessary to maintain discipline, was not so keen. An official inquiry into flogging in the army in 1835 came down squarely in favour, but reduced the number of lashes to a maximum of 300.

How the Weekly Dispatch, a London publication, came by the information about the Windsor flogging, when the local press was ignorant of this disturbing event is not known. However, to verify the facts, but possibly also to maintain friendly relations with army authorities, the editor of the Windsor and Eton Express sent a correspondent to the Infantry Barracks to get the details from the commanding officer before making his own report, which was published the following week:

The account of so revolting an occurrence created as well it might a great sensation in this town. Previous, however, to giving it publicity we thought proper to institute some inquiry as to its veracity and for that purpose communicated with the commanding officer on the subject. The result of this investigation has been completely to falsify the account published in the Sunday paper. What might have given some colour to the support is the fact that a drummer had been flogged and that a drummer also had been buried although it happened unfortunately for the respectable correspondent that the drummer who had been buried had never been flogged and that the drummer who was flogged has yet not been buried but on the contrary is alive and in good health. (3)

The incident as reported in the Weekly Dispatch and recorded by George Pridie tn quoted in many histories of Windsor,(4) but its denial by both the commanding officer of the regiment and the Windsor newspaper has never been taken into account. On the other hand, no one has ever tried to find out what really happened. It is difficult to establish the true facts today as no names were mentioned.

The first records consulted were the muster rolls of the Grenadier Guards.(5) They reveal that the only soldier in the regiment who died in May 1830 was indeed a drummer. His name was Nathaniel Loaring. He was in fact born in the Windsor Infantry barracks in 1800, son of a private soldier also called Nathaniel Loaring and his wife Elizabeth.(6) He joined his father’s regiment as a drummer boy aged 11 and may even have been at Waterloo with the regiment. He died in the Infantry Hospital, Windsor, on 14 May 1830. He was buried the same day, in rather a hurry one could say. There is no personal record for Drummer Loaring, to give some clue to the cause of his death or his military career. The muster books also show that no other drummer was either on a charge or in hospital.

Would the courts martial records of the Grenadier Guards give any clues? These records are kept at Wellington barracks in London and are very extensive, but there 1s a gap in the courts martial records for the four months the 1st battalion of the Grenadier Guards stayed in Windsor, that is from the end of April to the end of July 1830. However, a list of regimental courts martial at the National Archives show that Pte Richard Buckley had received 300 lashes in Windsor barracks on 26 April for being drunk on duty.(7) Could this be our man? But Buckley was not a drummer and his flogging had occurred nearly three weeks earlier, and he had not died.

All this suggests a cover up. If the commanding officer said that a drummer had been flogged in Windsor barracks, there must have been a court martial, but no records can be found. Could it be that Drummer Loaring was in fact flogged, and consequently died of it, and that his court martial record was spinited away? Why would a commanding officer of the Foot Guards state a falsehood to the local press, and why did vital courts martial records disappear?

The public was acutely aware of the ongoing criticism of military logging, and of the efforts of abolitionists in Parliament to put a stop to this barbaric punishment. A death by flogging in the Foot Guards, in a town like Windsor, would have given powerful ammunition to the abolitionists. Furthermore, the death of another young soldier in the regiment after a flogging twenty-two years previously may still have been in the memory of some of the men and officers. [One must remember that in those days a soldier served for life.

Jeremiah Robinson, like Nathaniel Loaring had enlisted as a drummer boy in 1804 at the age of fifteen.(8) However, Robinson had not grown up in the regiment. He came from Yorkshire, and after only one year of army life he deserted. Three years later he was re-captured, and on 5 January 1808 he was brought before a court martial, although he was only sixteen when he deserted and not fully attested. He was charged with desertion and selling one great coat, one blue coat, one waistcoat, one pair of breeches, one pair of boots, on hat and a stable dress.(9) His court martial record has clearly been tampered with Page two ends with the words: ‘The court is of the opinion that the prisoner is guilty of absenting himself from the Regiment and taking away some clothes the Property of Lt. Col. Kelley, and does therefore sentence him..‘ Page three of the document was carefully cut out, leaving just a narrow strip, which was signed by the commanding officer after this statement: ‘I approve of the proceedings of the above court martial and order the sentence to be put into execution’. But someone had scribbled at the top of page one in pencil, ‘received 6 January 280 lashes, taken down by the surgeon’.(10) The intervention of the surgeon means that the soldier was suffering unduly.

Robinson died in April that year as a consequence of his flogging. Even in 1808 this could have caused a public outcry, had it become general knowledge. Charles Knight wrote in his memoirs: ‘Military flogging was one of the forbidden subjects for editorial comment’.(11) They did not want to discourage recruits, many of whom came from the militia. In fact in 1813 William Cobbett spent two years in Newgate prison for criticising the flogging of Thomas Taylor, a militia man! The precautions taken by regiments to hide the fact that a soldier had died of such a death show a general anxiety about the whole issue. The question is how many other cover-ups were there?

In 1846 the highly publicised case of Private White of the 7th Hussars, who died after receiving 150 lashes at Hounslow, provoked many petitions from around the country. The resulting debate in Parliament to limit the infliction of corporal punishment in the army and the militia to 50 lashes(12) had some effect. The 1847 Mutiny Act reduced the maximum number of lashes to 50. The flogging debate, and in particular the death of trooper White encouraged the story and ballad writers. The last verse of one such ballad called The Flogging Excitement at Hounslow reads:

Then Britons all meet in Communion,

Petition the State and the Queen,

He ready, be willing, and soon then

To banish such disgraceful scenes;

May flogging be ever abolished,

At home and in nations afar,

No more let a soldier be punished,

Like White of the 7th Hussars.

Tied up hands and feet to a ladder,

While the sound of the cat reached afar,

Oh, Britain thy deeds make me shudder,

Remember poor White, the Hussar. (13)

The last soldier of the Grenadier Guards to be flogged in Windsor barracks was Pte Samuel Taylor, who received 50 lashes in April 1851 for disgracetul conduct. He had been discovered in an ‘unnatural position‘ with Pte Drew in the lock up room at Windsor barracks.(14) Drew was charged with being drunk, and was seen as ‘the innocent victim of a crime committed on him’. The word buggery was carefully avoided in these cases, because until 1861 it remained a capital offence. The final abolition of this punishment did not come until 1881, following yet another death of a soldier after receiving a ‘mere’ 25 lashes.

Brigitte Mitchell

References

- BRO, Notebook of George Pridie, WI/D 186/2.

- Weekly Dispatch, 16 May 1830.

- WEE 22 May 1839.

- for example, M Bond, The Story of Windsor (Newbury, 1984), p.77.

- National Archives, WO 12 1626, Muster Books and Payrolls.

- BRO Register of baptism, 1/26 MF 91042.

- Sational Archives WO 86 1.

- Grenadier Guards Description Books 1803-1822, [R154], Wellington Barracks.

- Courts Martial of the Grenadier Guards 1807-1813, [549], p.52.

- Ibid

- Charles Knight, Passages of a Working Life (London, 1864), p.132.

- Hansard LXXXVII 7 Aug. 1846, cc.374-463.

- c. Harding Frith, ‘Flogging in the Army’, JSAHR., 1 (1921), p.257; The Flogging Excitement at Hounslow printed by Bird London 1846.

- Courts martial of the Grenadier Guards, vol. 577, 28 April 1851.