Published in Windlesora 15 (1997)

© WLHG

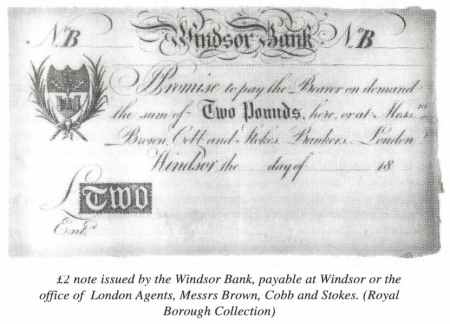

Between 1801 and 1816 Windsor had three banks, a large number for such a relatively small town; its population in 1811 was about 5,000. Two of the banks had been founded by a local ironmonger, James Coombs, in 1801. They were known as the Windsor Bank and the Windsor and Eton Bank, and it is likely that the latter was in Eton, although some bank notes were printed with Windsor as their place of issue. The third bank, also known as the Windsor Bank, was founded by Richard Ramsbottom, MP for Windsor and a local brewer, in about 1780. It was quite common at that time for more than one bank to have the same trading name, and presumably customers distinguished them by the names of the proprietors.

In the late 18th and early 19th century, it was usual for banks to be run by sole traders or by a small number of partners, since before the days of the Companies Acts, incorporation of a business could only be achieved by Royal Charter of a private Act of Parliament. An Act of 1708 had limited the number of partners to six, and until 1826 limited liability banks were forbidden by law and the partners were jointly and severally liable for all the debts of the partnership. As a result, most banks were single office banks. These restrictions probably explain why James Coombs set up two banks, with separate finances, rather than a main bank in Windsor and a branch in Eton.

Some partnerships were stable, but others, such as the Windsor Bank of James Coombs, changed quite frequently. It is often impossible to be sure exactly when individuals joined or left a partnership. The dates on bank-notes provide some clues, but the small number of surviving notes inevitably means that the picture is not complete. The partnerships of the Windsor Bank went through several permutations during the fifteen years of its existence. In 1809 Coombs went into partnership with Henry Brown and by 1813 the bank was trading under the name of Coombs, Brown, Coombs and Co. The second Coombs would appear to have been James Jnr, son of the founder, who had been brought in to ensure the continuance of the family business. However, James Coombs Snr died in October 1813 and the name changed to Brown and Coombs, and remained as such until the bank closed in 1816.

There were some fundamental differences between banks of this period and today. One of the most important was that most banks issued their own notes. The Bank of England did not have the monopoly as it does today, and its notes were not in general circulation outside London. Instead provincial banks used Bank of England notes for settling bank debts outside their own town and neighbourhood, where their own notes were not known or acceptable.

Bank-note issuing could be a very profitable side of the bank’s business since it was a way of borrowing money from customers interest free, in order to lend it at a profit. Customers paid into the bank in gold and silver coins and received paper bank-notes (which could be printed for next to nothing) in return. Stamp duty, however, had to be paid on each bank-note and such notes could be circulated only once unless the bank held a banker’s licence. (1) When they were returned to the bank they were destroyed. In the meantime, however, the cash paid in by customers could then be used by the bank to lend at a profit – as banks do today. The great increase in the number of provincial banks which took place in the late 18th and early 19th centuries played a vital role in financing the Industrial Revolution.

Apart from note issuing, the other main functions of early banks were: lending money, accepting savings, making payments to customers and third parties, and dealing with the bills of exchange, a type of promissory note which was used to finance trading.

Issuing bank-notes under their own name was, of course, a form of advertising which might well encourage anyone handling the notes to open their own account. However, there was one serious disadvantage. Banks were legally bound to repay each and every one its of notes in cash on demand, and if for any reason the public lost confidence in the bank’s ability to pay, customers might quickly demand that their notes be exchanged for coins. It was an act of bankruptcy, not to be able to meet any such demand. It was for this reason that provincial banks issued notes drawn on a London agent who, amongst other things, would act as banker to the county bank. In normal circumstances a run on a local bank could be met by borrowing money from the London agent. The money could be sent by stage coach or postchaise, though highwaymen still posed a very real risk.

The choice of which particular London agent to use was largely decided by the nature of the business of the country bank. The Windsor Bank of Brown and Coombs drew for its trader customers on Williams and Co. of Birchin Lane, London, and for its gentry class customers, including those living in the precincts of Windsor Castle, on Birch and Chambers of New Bond Street. The bank also used Brown, Cobbs and Co. of London. (2)

In 1801, when James Coombs founded the bank, England had been at war with France for eight years. For farmers and many traders it was a time of prosperity and prices rose dramatically. Wars, however, are expensive and a drain on the country’s reserves, and the naval blockade of Europe had adverse effects on home industries, resulting in widespread unemployment in some area. Peace in 1815 brought a slump in the prices fetched for corn causing the cost of bread to rise and the discharge of soldiers and sailors brought increased unemployment. The country suffered from severe economic difficulties, which led, amongst other things, to a country-wide banking crisis. Many provincial banks went out of business – amongst them those of Brown and Coombs.

At the end of January 1816 Abraham Chambers, a member of the West End agents, Birch and Chambers, had visited the Windsor Bank to inspect the books and give advice. He was clearly worried about its financial situation. It had been insecure since the death of James Coombs Snr in 1813, not least because it was encumbered with debts incurred by his ironmongery business. The situation worsened and James Coombs travelled to London for further consultations, but after a long conversation and another look at the accounts, Mr Chambers said that he was obliged to ‘suspend making payments for Brown and Coombs.’ He did so on Tuesday 13th February.

The next day the Windsor Bank failed and two days later the partners were declared bankrupt. On 18th February the Windsor and Eton Express carried an announcement that there was to be a meeting of the bank’s creditors at the Guildhall and a meeting of secured creditors at the White Hart Inn – now Ye Harte and Garter. Details of the bankruptcy were given on the back page of the newspaper. The bank’s balance sheet revealed that £23,870 was owed to the London agents and bank-notes worth £17,789 were still in circulation – and in theory should have been redeemable for coins. After all the assets and liabilities had been accounted for, there was still a shortfall of £22,040. (3)

All the assets of James Coombs, including the family ironmongery shop were seized by the assignees appointed by the bankruptcy commissioner. In March the Windsor and Eton Express carried a notice informing the public in general that the whole of the ironmongery stock-in-trade was now selling ‘at very reduced prices’ and that such a sale could only be continued for a short time. In May the ‘very extensive and well selected stock’ which remained after the clearance sale was sold by an auction held at the premises.

In June 1816 the bankruptcy commissioners held an enquiry in the Guildhall and summoned Henry Brown and James Coombs to appear before them. Their answers, however, did not satisfy the commissioners and both men were taken into custody pending further examination. Much of the disputed evidence related to the burning of £17,000 worth of Windsor bank-notes after the failure of the bank. The commissioners believed that the notes had been circulated, paid into the bank for cash, and were thus of no value. It is perhaps coincidence – or suspicious – that the value of notes burnt was equal to the value of the notes said to be in circulation at the time of the collapse.

Brown and Coombs were held at Newgate Prison in London and were individually tried at the Court of Chancery. But after a lengthy hearing it was decided that the charges against them were unproven and in August the two bankrupts were released.

Their inability to survive the financial crisis was only one of many such failures. So what were the circumstances that made their business fail, while others like those of Richard Ramsbottom did not? The death of James Coombs Snr had left the bank encumbered with debts incurred by his ironmongery business. James Coombs Jnr, it would seem, was not a good ironmonger, and by his own evidence given to the bankruptcy commissioners, knew little about the business of a banker. But there was another significant factor which was mentioned, but not fully explained, in the records of the High Court of Justice in Bankruptcy. According to these, the Windsor Bank was severely handicapped by having substantial assets locked up in ‘unwise advances’ to residents of Windsor Castle. The Prince Regent (later George IV) was himself frequently in financial difficulties, but there is no evidence that he ever used the Windsor Bank and the residents in question could have been any of the great number of people who lived within the Castle precincts – that must remain a mystery.

Derek Hunt and Judith Hunter

Derek Hunt is a retired bank manager with a special interest in the history of bank-notes. Judith Hunter is a local historian and honorary curator of the Royal Borough Collection.

Notes

- A bankers’ licence could be brought from the government. It was not a licence to bank (which was not needed), nor to issue notes, but merely to issue re-issuable notes.

- It is not known whether there was a connection between Henry Brown of the Windsor Bank and the Brown of Brown, Cobbs and Co., though it may be pertinent that this bank also failed in 1816 and no trace of the firm has been found after that date.

- According to figures supplied by Barclays’ Bank, this sum is worth around £750,000 in today’s money.

Acknowledgements and Sources of Information

Country Banking in the Industrial Revolution by L S Pressnell (Oxford 1956).

The Standard Catalogue of Provincial Banks and Banknotes by G L Grant (Spink & Son 1977).

Windsor and Eton Express for various dates in 1816.

Examples of notes issued by Windsor banks are held by the British Museum, the Bank of England

Museum and by the Royal Borough Collection, Windsor.

The authors would like to express their thanks for the help so generously given by Virginia Hewitt, curator of Paper Money at the British Museum, and the staff of the Bank of England Museum and Slough Library.

A notice to creditors of Messrs. Brown and Coombs, which appeared in Windsor and Eton Express, February 20th 1816. (copy of newspaper courtesy of Slough Library).

The notification of sale of the assets of James Coombs, from Windsor and Eton Express, April 21st 1816 (copy of newspaper courtesy of Slough Library).