Windsor’s First Family 1680-1777

Published in Windlesora 25 (2009)

© WLHG

‘Come hither, you little bastard,‘ Nell Gwyn is reputed to have called to her son by Charles II. When the King reproved her ‘she told him she had no better name to call him by’ (he was named Charles after his father at his birth in 1670, but sons by aristocratic mistresses had been ennobled immediately).1 The King responded first by giving the boy the surname Beauclerk and the title Earl of Burford, then when he was 14 created him Duke of St Albans. He went further and in the same year, 1680, presented Nell with a fine new Windsor home, to be for her and afterwards her son and his male heirs.

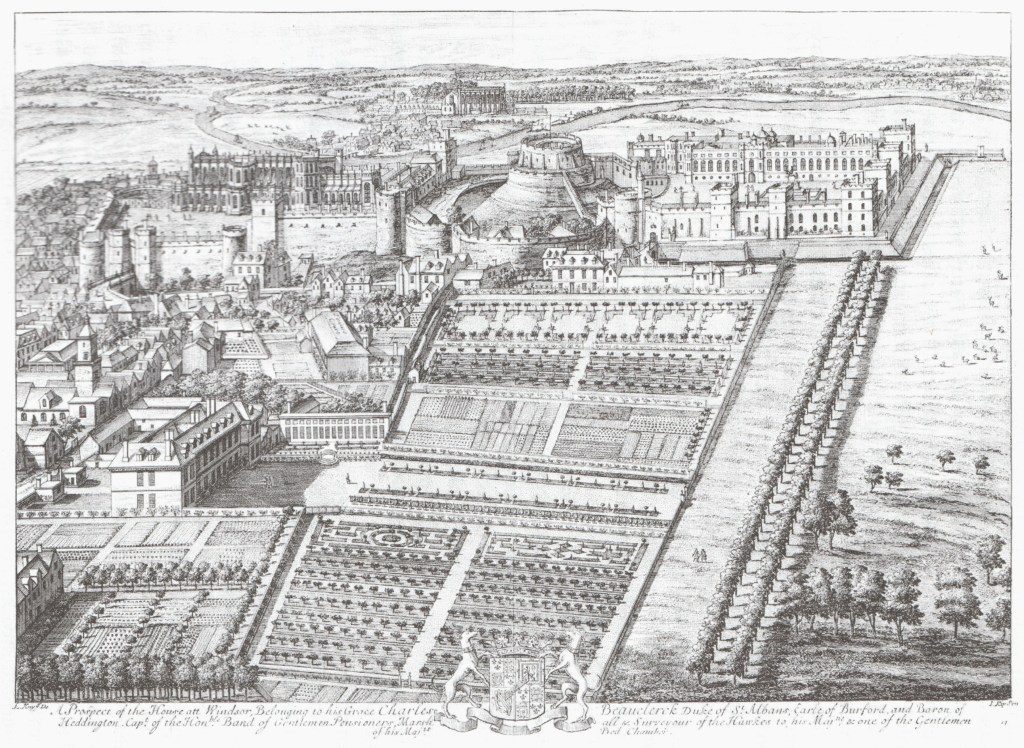

Burford House, as it became known, was built of red brick on land bordering Priest Street at the back of the Castle, where once there had been a vineyard. The house, possibly designed by Hugh May, was handsomely appointed and had a staircase decorated by the artist Verrio with murals of scenes from Ovid. Nell made it her principal residence outside London, and acquired land adjoining it from the Dean and Canons of Windsor. Three documents in St George’s Chapel Library, dated 11 December 1684, record the terms of the indentures; for the first, formerly a back garden and stable in Priest Street, Nell was to pay 12 shillings rent on the feasts of the Annunciation and the Blessed Virgin Mary.2 The second was a piece of a back garden, and the third ‘more or less’ two acres, consisting of ‘tenements, garden and orchard’ for which she paid 28 shillings ‘of lawful money of England’ and rent of 15 old pence twice a year. Seals are appended to the documents, signed by the illiterate Nell with the carefully-formed initials she had learned to write: EG.3

These initials are also found on a letter she dictated from Burford House in April that year, to her dressmaker Mrs Jennings, who lived ‘over and against the Tub Tavern in Jermyn Street, London’, reminding her of the ‘gold stuff” and other expensive items that Mrs Jennings should have sent her. No doubt she obliged quickly, and Nell lived to enjoy her wealth till 1687, after the death of the King, when Burford House passed to her son. For nearly a hundred years thereafter the Beauclerk family were to be intimately involved with Windsor affairs, serving Court and town variously with such appointments as Lords Lieutenant of Berkshire, Constables of the Castle, High Stewards of Windsor, Mayors and Members of Parliament.4

Like his mother, the first Duke of St Albans added to his property, and it is recorded that on 23 April 1691 the Corporation granted him a lease of ‘waste ground’, 20 feet by 18 feet, fronting Priest Street, for a fee of £3 and annual rent of a shilling. He later commissioned a bird’s-eye view of the whole property by Leonard Knyff, showing the house, orangery, and beautifully laid-out gardens below the south side of the Castle — thus emphasising the St Albans’ close connection with royalty.5

When his mother died the Duke was only seventeen and Burford House was leased to Prince George, husband of the future Queen Anne. The Duke was went by his uncle, James 11, to join the army of the Emperor (engaged in pushing the Turks back from the Danube). This meant that in 1688, when James II was deposed, he avoided embarrassment by being out of the country. Having distinguished himself at the Battle of Belgrade (1688), he joined William III, fighting in Flanders against the Spanish. But when he came into his inheritance at twenty-one, he abandoned soldiering and lived at Burford House.

When Belgrade was taken the Duke had captured (rescued?) two small Turkish boys, who then became part of his household. They seem to have settled down in Windsor for on 17 June 1704 George and Charles Mustapha (named presumably for Prince George and the Duke himself), then aged ‘about 23‘, were baptised in Windsor Parish Church, the Duke of Northumberland and the Duchess of St Albans standing witness. George later returned home (wherever that was), but Charles stayed on in Windsor and in 1742 George II created him a Poor Knight.

The Duke married Lady Diana de Vere, daughter and heiress of the the last Earl of Oxford, and they had twelve children, many born at Burford House.6 Again Windsor Parish Registers bear witness, though some entries are sad: the Baptismal Register records that on 29 January 1706 the Lord Seymour was baptised, but the Burials record shows that only the next day, 30 January, he was buried. Three daughters, Diana, Mary and Ann, died very young too.

The first Duke became Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire, and on 7 September 1716 was sworn in as High Steward of New Windsor. At the same time ‘his Grace the Most Noble Charles Duke of St Albans was sworn a Freeman of this Corporacion’ [sic], and presented with a silver box. The records of the Chamberlain (Treasurer) show that it cost £4.15s 6d, but to obtain it the Chamberlain had been to London, the expenses ‘ffor my horse & selfe 4 dayes att London to gitt the Box made’ adding a further £1.10s. to the cost.7 This award to the Duke is no surprise, but we may think it odd that in 1723 the Duke’s cook, Francis Biard (from the spelling perhaps French) was made a freeman; likewise the following year one Lawrance Ainsworth, simply described as ‘servant to his Grace’. To be given the freedom of the town was an honour then as it is today, but it could also be bought by those wanting to trade in the town (anyone native to the town was automatically a freeman), as it was by a Thomas Smith of London, a goldsmith, for 10 guineas, on the same day as the cook got his freedom ‘att the request of his Grace’. The Beauclerks exercised a certain droit de seigneur in Windsor, though why freedom was needed for servants is unclear: perhaps it was to bind a man to his service, the Duke valuing his dinners and not wanting another nobleman poaching his chef.

Following the Duke’s death in 1726 (he was buried in Westminster Abbey) his eldest son, another Charles, succeeded to the title. But there were still six children living with their mother at Burford House, and this Duke never took up permanent residence, sometimes renting accommodation nearby, sometimes living further away and returning to Windsor for court or civic functions, When he became Warden of Windsor Forest in 1730 he moved into Cranbourne Lodge as official residence, though this brought him into conflict with the Ranger of Windsor Great Park, the formidable Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough. He called her the ‘Old Fury’, and she called him that “insolent idiot” and tried to prevent him from setting foot on what she regarded as Aer territory. George II, who favoured the Duke, allowed him to make a door from Burford Lodge into the Home Park, and he had permission to drive on chaise with one horse through it to reach Cranford Lodge; on one occasion however, he pushed his luck with a coach and four. She retaliated by chaining up the gates from the Great Park to Cranbourne. Only her death ended the feud.

Most of the first Duke’s sons distinguished themselves in their own right, and played a part in Windsor affairs. The second son, Lord William Beaucelerk, became Vice-Chamberlain to the Queen, with a room in the Castle, Vere was a naval man, rising to the rank of Admiral and given his own title of Baron Vere of Hanworth.8 He would have been created the first grovernor of Newfoundland had he not been elected MP for New Windsor in 1726, which precluded the holding of civil office. He served as one of Windsor’s two MPs until 1741; he was also an alderman, but when his turn came to be Mayor in 1734 he begged leave to decline, ‘it being ill convenient lor several reasons’.9 The excuse was accepted, but probably the more readily as he presented £30 for a civic dinner, the same amount as was normally awarded a new mayor, for that purpose. Despite their origins, the Beauclerks may not always have relished their association with the town’s tradesmen; the second Duke once wrote drily to a correspondent: ‘My friends in the corporation dine with me. We shall be about twenty. I am sure you envy me.’

Of the other sons, Lord George, an army man, served as a Windsor MP from 1744-54, was made a freeman of the town in 1744 and served on the corporation, offering excuses for not becoming Mayor with a £30 sweetener in 1752.10 Lord James made the church his profession. He served as a Canon of Windsor from 1743-46 before becoming Bishop of Hereford. Later in life he hoped to be made Dean of Windsor, but in that ambition he was thwarted.

Of all the Beauclerks probably Lord Sidney had the most presence in Windsor (and was the only adult Beauclerk to be buried in the Parish Church). He served New Windsor as MP from 1734 until his death ten years later, and acted as a bencher, alderman and Mayor of Windsor, though he asked in 1741 to be excused the office before his year was up.11 The Hall Book records that the Court returned his Lordship ‘thanks for having done them the honour to accept of and serve the same office’.12 Sidney was described by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu as being ‘Nell Gwyn in person with the sex altered’, with all her ‘beauty, od qualities’, and no doubt he exercised his charm on the grocers, butchers, bakers etc of the Corporation. Less amiably he was a fortune hunter; he married an heiress but not satisfied persuaded his fellow MP, Richard Topham, to leave him his estates in his will. In return he named his eldest son Topham, and in due course Lord Sidney and the then five-year-old Topham inherited land in Clewer, Dedworth and the Brocas, as well as a handsome house called Pilgrim Place between Peascod St and Bachelors’ Acre.

Topham was a cultured man of the Enlightenment, a Fellow of the Royal Society, amateur chemist and bibliophile (by his death he had amassed 30,000 volumes), but also a typical young aristocrat in his self-indulgence and amorality. Yet he became a friend of the great lexicographer and man of piety Dr Samuel Johnson, who was fascinated by his connection with Charles II and attracted by his lively wit. On one occasion, Topham persuaded Johnson to visit him in Windsor; they walked out on a Sunday morning and entering a churchyard Johnson laid himself down on one of the tombs, despite the sounds of service in the church. ‘Now, Sir,’ said Beauclerk, ‘you are like Hogarth ‘s Idle Apprentice’.13 This must have been before 1766 when Topham wold his Windsor property to Sir Edward Walpole, the Prime Minister.14

George, 3rd Duke of St Albans, was a rogue. He held the usual high offices but neglected them all; he fathered his first bastard while still at Eton, and though he married an heiress they soon separated. Having run up considerable debts he escaped to Paris with a Windsor dairy-maid called Molly, by whom he had a son. But he was soon making his philandering way across the rest of the continent. Like his father and grandfather before him, he was High Steward of Windsor, but his continued absence from Windsor tried even the admiration of the council for the family, and in 1768 they threatened to replace him. He returned just in time to be reappointed, and perhaps to make amends, in 1771 found the funds to distribute £400-worth of coal, candles and bread to the town’s poor.15

Ultimately the 3rd Duke cut his ties with the town completely, in 1777 selling Burford Lodge for £4000 to King George III, who renamed it Lower Lodge and made 1t the home of his three youngest daughters. Then George IV faced the brickwork to match the rest of the Castle and Nell Gwyn’s home lost any distinct identity. Today it is part of the Royal Mews and is rarely pointed out by tour guides. All that is left of the Beauclerk family, once so dominant in the town, 1s preserved in the renaming of the road in which they ance lived: St Albans Street.16

Hester Davenport

References

- James Granger, A Biographical History of England, 1775, Vol. 111, p.211.

- SGC XE.N.9. The other documents are SGC XI.N.7 and SGC XI.N.5.

- For more about Nell Gwyn see Sheila Rooney, ‘Our Pretty Witty Nell” in Windlesora 16.

- For details see Shelagh Bond (ed.) The First Hall Book of the Borough of New Windsor 1653-1725, and Jane Langton (ed.) The Second Hall Book of the Borough of New Windsor 1726-1783, the Royal Borough of New Windsor, 1968 and 1973. Other sources include Donald Adamson & Peter Beauclerk Dewar, The House of Nell Gwyn: The Fortunes of the Beauclerk Family l670-1974, William Kimber, 1974, Charles Beauclerk, Nell Gwyn: A Biography, Macmillan, 2005 and the online Oxford DNB.

- A note beneath the engraving reveals that the Duke had been made Captain of the Honourable Band of Gentlemen Pensioners, Marshall and Surveyor of the Hawks and a Gentleman of the King’s Bedchamber. The King once sent the Duke as an emissary to France, presenting him with a set of 6 coach horses, ‘spotted like leopards’, to ensure his reception.

- He had shown his paternal inheritance earlier however. I can’t resist referring to his pursuit of an actress called Hester Davenport, whom he tricked into his bed after a supposed ‘marriage’ conducted by a friend disguised as a priest.

- ‘RR Tighe & JE Davis, Annals of Windsor ii, p.507.

- Another brother Aubrey was a naval hero. He died in action against the Spanish in the West Indies in 1741, when despite both his legs being shot off he refused medical attention until his last orders were given.

- Aldermen were expected to take their turn at being Mayor, and could be fined if they refused unreasonably.

- In 1767 the council accepted that the Colonel’s posting in Scotland was a ‘legal and reasonable’ excuse for not becoming Mayor.

- Windsor council was a self-perpetuating oligarchy; members started as brothers, progressing to benchers and aldermen.

- He likewise gave up being Chamberlain.

- This anecdote is recorded in Boswell’s Life of Johnson.

- In later life he became exceedingly careless of personal hygiene. Once when everyone started to itch at a party at Blenheim the problem was traced to Topham who unblushingly declared that he had ‘enough lice under his wig to stock a parish’. For this and his marriage to Lady Diana Spencer, see Carola Hicks, Improper Pursuits: the Scandalous Life Of Lady Di Beauclerk, Macmillan, 2001.

- He had managed to acquire some money through the lease of land in the Strand to the Adam brothers, who turned it to profit in the Adelphi estate.

- The first mention of the name is in a lease of 1806 (Brigitte Mitchell [ed.], Streets of Windsor & Eton, Windsor Local History Publications Group, p.26). On the third Duke’s death virtually all the paintings and other valuables from Burford Lodge were sold.