1793-1813

Published in Windlesora 22 (2006)

© WLHG

The first Windsor theatre to call itself ‘royal’, boldly if illegally, was no better than a converted barn in the middle of a ‘dirty farmyard’ at the bottom of Peascod Street. Yet for fifteen years from 1778 to 1792, it kept going, licensed for a few weeks in the summer when the Eton boys were on vacation (it was feared that exposure to the stage would be corrupting). The company was an offshoot of Richmond Theatre; on their off-days, volunteer players would pack themselves into coaches, along with their costumes, scenery and instruments, and bump their way to Windsor. They were under the management of Francis Waldron (1743-1818), who had worked for Garrick at Drury Lane and was also something of a playwright. But he was handicapped with a lisp, and in London never rose above the level of playing eccentric old men and such minor characters as the Second Gravedigger in Hamlet. Perhaps he promoted himself when he brought Hamlet to Windsor in the summer of 1792, when Hamlet himself was played by Robert Benson (1765-96), cited as co-manager with Waldron, and again a player of supporting roles on the London stage. Noting the performance, the Thespian Magazine commented: ‘This Theatre (we cannot conceive how it’s royal), is so remote from the town that we do not wonder at the thin audiences.’

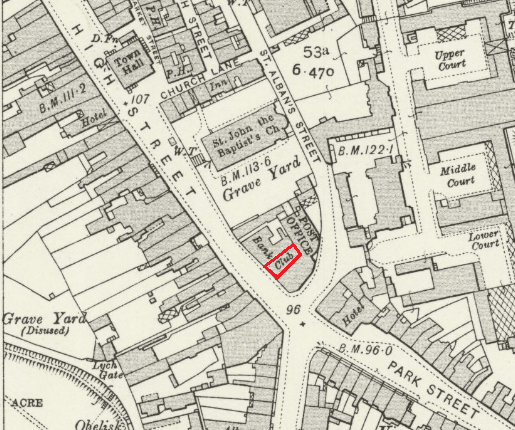

But the appetite for drama had been shown, and the following April, the same journal was ‘happy to find that a new Theatre is now erecting in the middle of Windsor’. It was situated in the High Street and was the second building beyond the parish churchyard towards the junction with St Albans Street – in the twentieth century it was used until demolition by the Constitutional Club.

Windsor New Theatre opened on 12 August 1793, with a performance of Everyone has his Fault, a comedy by Elizabeth Inchbald first seen in London the previous year with a plot revolving round characters unhappily married and others unhappily unmarried: a Mr Harmony puts all to rights. The second half of the bill was Rosina, a new comic opera by Frances Brooke.

The audience was said to be ‘very numerous and fashionable’, but that number was relative to the size of the theatre. The auditorium was frequently described as ‘elegant’, but in an age of immense theatres — Drury Lane and Covent Garden seated over 3,000 — this one was minute. King George III and Queen Charlotte who became regular attenders as in London (and Windsor’s theatre soon earned the right to call itself the Theatre Royal), probably enjoyed the greater sense of intimacy which the new theatre provided. As a boy, the author and publisher Charles Knight was often in the audience, and he conveys its cosiness when he writes that ‘her majesty’s apothecary in the lower boxes might have almost felt her pulse across the pit’. The theatre was run by actor/manager Henry Thornton (1750 – 1818), a shrewd if eccentric businessman, who had a string of theatres under his command, including Newbury, Andover, Henley and Reading. According to Knight the royal box was furnished with capacious armchairs (and was probably, like the principal box at Newbury, lined with crimson damask), while the rest of the theatre consisted of two tiers of boxes at 3 shillings, where the lower tier on the left-hand side was reserved for the court, the pit (today’s stalls) where seats were 2 shillings, and a gallery for which 1 shilling was charged.

The programme changed daily, and to inform the public, playbills were circulated, and large ones were pasted up outside the theatre and elsewhere. The entertainment traditionally involved two plays, a full-length ‘main-piece’, and a shorter ‘after-piece’ which was always a farce or a comic opera. In between, there would also be a song, dancing, or even a circus act.

As well as the actors, a company had its musicians and its backstage workers, who would have to effect a considerable number of scene changes during the course of the evening. It was an age of spectacular scenic effects, and though the Windsor theatre was small it would have had its machinery to change backdrops and wings, operate shutter mechanisms, work trapdoors, raise and lower clouds or heavenly chariots, and create water and fire effects. Lighting was more sophisticated than might be imagined; the stage directions for Rosina, for example, specify that ‘in the first act the sky clears by degrees, the morning vapour disperses, the sun rises, and at the end of the act it is above the horizon’, declining slowly through the second act. Thornton would not have chosen it to open with if he could not have impressed the Windsor audience with such technical bravura.

The Royal Family did not seem to have attended the opening night but with five of the princesses, they were present at a performance of George Farquhar’s The Beaux Stratagem (1707) followed by Inchbald’s popular farce Animal Magnetism (1788), which went off with ‘much éclat’. Playing in both was John Quick, one of the King’s favourite comic actors; the King’s enthusiasm for the stage gave Windsor the opportunity to see some of the best performers, commanded there by His Majesty; another favourite was the comedian Dickie Suett, and Knight recalls his hearty laughter and how he would cry out ‘“Bravo, Quick!” or “Bravo, Suett!’’’.

By the end of the first short season (the terms of the license were as before, with extensions allowed at Christmas and during Ascot week), the Royal Family had attended the theatre seven times, most gratifying to the manager. Charles Knight, who was born in 1791, began his play-going when he was seven years old, so his memories are not of the early years, but the rituals he describes must have been established from the outset. He tells us that the court party would usually walk to the theatre, where at seven precisely.

Mr Thornton made his entrance backwards, through a little door, into the stage-box, with a plated candlestick in each hand, bowing with all the grace that his gout would permit. The six fiddles struck up ‘God save the King’; the audience rose; the king nodded round and took his seat next the stage; the queen curtsied, and took her armchair also.

At the end of the third act, coffee was served, and at eleven the performance finished, ‘the flambeaux of three or four carriages gleamed through the dimly-lighted streets, and Royalty was quickly at rest’.

Many were the stories told of Henry Thornton. He was notably forgetful, often riding to London to fetch something for the theatre and coming back without it. Once he sent to his wife for a clean shirt; she replied that she had left four in his dressing-room, and it was discovered that he was wearing the lot. Another time, he was called to the Castle but forgot to take off his make-up, appearing in the guise of a Moorish chief, ‘his face decorated with an enormous pair of whiskers’, to the great amusement of the ‘illustrious personage’ who had summoned him. As an actor, Thornton was waspishly described (in the Thespian Dictionary) as one ‘who can bustle through a part with considerable ease, though unacquainted with the author’s words’. The King once mildly commented of his performance that it had been very well, but quite different from the character he had seen in London.

The manager could be laughed at, but the play-house was an asset to Windsor, not only bringing entertainment but giving cultural status and affinity with the metropolis. Thornton put on the latest popular successes, in 1800 even staging Sheridan’s 1799 tragedy, Pizarro. Because England was at war with France and Spain, this heroic drama of courageous Peruvians defying cruel Spaniards struck a patriotic and popular note. But it was designed for the huge Drury Lane stage, and required a large cast and tremendous scenic effects. Yet even on Windsor’s tiny one, the playbill advertised a ‘Temple of the Sun, and Peruvian Altar, on which descends sacred Fire’, a storm, and at the drama’s climax a waterfall bridged by a fallen tree across which the hero escapes through gunfire, flinging the tree-trunk down behind.

Knight as a boy would have wanted to see Pizarro, and perhaps was old enough the previous year to have been at Susannah Centlivre’s A Bold Stroke for a Wife (1718).* This performance, commanded by their Majesties for Ascot week, was an evening which starred John Bannister* (1760-1836) from Drury Lane, another royal favourite. Bannister was a brilliant mimic, ideally suited to play Colonel Feignwell in A Bold Stroke.., since the character has to adopt four disguises to win the hand of Miss Ann Lovely (played at Windsor by Thornton’s daughter). By her father’s will all four of her guardians must agree before she can marry, so Feignwell attempts to ingratiate himself with each in turn, becoming a fine gentleman of France to impress Sir Philip Modelove, a bearded traveller and curio-collector to fool the virtuoso Periwinkle, a Dutch Mynheer for Tradelove, and a stern Quaker for Obadiah Prim and his wife. Complications inevitably arise, but all ends as it should.

Bannister also appeared in the afterpiece and sang a comic song between the two plays, deserving whatever he earned. Actors were also customarily rewarded with benefit nights, when the evening’s profits were entirely theirs. The present Theatre Royal has a large framed playbill of 11 January 1803, for ‘Mr Quick’s Night’, when by royal command Quick played Dromio of Ephesus in Shakespeare’s Comedy of Errors, starred in the afterpiece, and performed a comic sketch by Samuel Foote called Lady Pentweazle. No doubt the house was full, and he did well.

So from year to year life went on in the Windsor Theatre. But the King was growing infirm, Thornton had his problems with gout, and the auditorium was showing its age too: Knight writes of its ‘dingy green curtain’. Running a theatre that was empty for most of the year was not financially rewarding, and it was a sad fact that even when open full houses were only assured when royalty was present. In 1805 it was reported that Thornton was trying to dispose of the concern, and in 1807 the building was purchased by Congregationalists for conversion to a chapel, though the theatrical lease ran until 1813.*

By then, there had been a significant change to Windsor life. On Saturday 1 August 1812 the Windsor Express was founded by the two Charles Knights, father and son, and from then on information about the theatre and performances became easier to obtain. The managers were now Sampson Penley and a Mr Jonas (his first name is unknown), who announced on the front page of that first Express that ‘they have spared neither Pains or Expense in providing a company from the Theatre Royal, London, and in bringing forward every Novelty for Amusement, which they trust will merit the patronage they have hitherto so liberally experienced’. That night, the season opened with Daniel Egerton in Macbeth, the Express reporting a ‘very elegant audience’. Mr Jonas had been a puppeteer at Bartholomew Fair, and puppet shows (suitable for such a small theatre) became a part of the repertoire. Sadly, the King had lapsed into senility and his great guffaws were no longer heard. There were occasional performances by command of sixteen-year-old Charlotte of Wales, the Prince Regent’s daughter, but she did not necessarily attend.

The rest of the summer programme consisted of the usual variety of comedies, farces and a few tragedies, with the management engaging the distinguished actress Jane Powell (1761-1831). She had a fine speaking voice, and with her tall and elegant figure she regularly took on breeches roles; on 17 August, she played Hamlet and spoke the ‘Monody on the Death of Sir John Moore at Corunna’ (in the midst of celebrations for Wellington’s victory at Salamanca). The Christmas season brought William Betty (1791 – 1874). He had had an extraordinary success at the age of fourteen, when playgoers flocked to see him play adult roles which included Hamlet, Richard III, and even Macbeth. But infant prodigies grow older, and in Betty’s case fatter; ‘Bettymania’ was soon over. However, the actor acquitted himself reasonably well, Hamlet being his best role according to the Express.

Next year, 1813, was the theatre’s last. It was notable for the first appearance on the Windsor stage, during Ascot week, of Dora Jordan (1762 – 1816), as Violante in another of Mrs Centlivre’s plays, The Wonder; A Woman keeps a Secret (1714). Mrs Jordan was the greatest comedienne of the day, and had been engaged at other of Thornton’s theatres, but as the mistress of William, Duke of Clarence, she had stayed away from Windsor. But now, despite the ten children she had born him, she had been set aside; the engagement at Windsor may partly have been defiance.

The little ‘cockpit’ (Knight’s word) finally shut its doors on 5 September. Probably because of awareness of the impending closure, it finished with a ‘serious loss on the season’.

Yet, phoenix-like, it was reborn. The following year, the Express announced that £1,000 had been collected towards the building of a new theatre, and a site was found at the bottom of Thames Street. On 6 August 1815, Messrs Jonas and Penley were able triumphantly to address ‘The Nobility, Gentry, and the public of Windsor and its Vicinity’, and inform them that the new theatre ‘having been erected in a commodious and substantial manner, and decorated in a superb and elegant style, by Masters of the first eminence, will be opened on Monday, August 21st, 1815’, with Sheridan’s The School for Scandal as the main piece.

There was also a Prologue, written by Charles Knight. Beginning ‘Where shall the Muses fly, in this cold age/When hood-winked Zeal proscribes the graceful stage’, it addresses the anti-theatre prejudice which many blamed for the closure, reminding the audience of the great names associated with dramatic writing. Knight sees the new theatre as a ship setting out on its maiden voyage, and concludes:

Nothing dismay’ d, again we tempt the seas. The ship’s afloat, — the WINDSOR courts the breeze;

Well rigg’d and mann’d her jocund course she steers, Proud of her lading! Shall we say — three cheers?

No doubt the cheers echoed to the rafters of the Second Theatre Royal.*

Hester Davenport

Notes

*This building lasted until 1908, when it burnt down. The present Theatre Royal was built on the same site, opening in 1910.

Sources

A History, undated account published by Windsor Theatre Royal Gilliland

Thomas, The Dramatic Mirror, containing the History of the Stage, 1808

Hedley, Olwen, Round and About Windsor and District, 1948

Highfill, Philip H., et al, A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & Other Stage Personnel in London, 1660- 1800, 16 vols, 1973-93

Hume, Robert D. (ed.), The London Theatre World, 1660-1800, 1980

Knight, Charles, “Windsor, As it Was’, in A Volume of Varieties, 1844, Passages of a Working Life during Half a Century, 1864

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The Thespian Magazine, 1792-93

The Thespian Dictionary; or Dramatic Biography of the Present Age, 1805

The Windsor Express, 1812-15

Winston, James, The Theatric Tourist; being …brief and authentic historical accounts of all the Principal Provincial Theatres in the United Kingdom, 1805