Published in Windlesora 05 (1986)

© WLHG

The history of the Eton town school which has for long been known as ‘the Porny‘ is relatively well-known in outline (the embarrassment of an apparent connection with an unattractive word is as recent as society’s fascination with that subject). But recently a sizable black metal box emerged from the depths of a bank vault, containing early account books and other documents; the information in them, and in the records of various sorts held in the muniment room in Eton College, make possible a fuller account than any yet published of the earliest years of the school. It is important to remember that it was not founded by Mark Antony Porny, as is often claimed – a smaller earlier school was so generously endowed by him that a long life for it was virtually assured.

Mark Antony Porny, born Marc Antoine Pyron du Martré, was a Frenchman who came to England at the age of twenty-three in 1754. He taught French and Italian to Eton College boys, wrote books on French grammar and on heraldry, lived a frugal life and died a Poor Knight of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, in 1802. In his Will (1) he bequeathed the bulk of his estate “upon trust unto the Treasurer of the Charity and Sunday School established in the Parish of Eton Anno 1790“, requiring that it “shall be applied by the trustees or committee or by whatever name they may be designated for the time being… towards carrying on the laudable and useful designs of its institution…“

The history of this earlier school was that in 1790 William Roberts, Provost of Eton College, had been the prime mover in the establishment of a charity school for the children of the townspeople. In a handbill dated 2 March of that year, the inhabitants of Eton were invited to contribute towards setting up and supporting a Sunday School and a charity day school for a limited number of both boys and girls, to be under the management of the principal inhabitants of the town. The Sunday School was to be open to all children (except, almost certainly, any who were illegitimate), and from their number twenty-one boys and fifteen girls were to be elected to places in the charity day school (2). Here the children were to be taught reading and writing; the Sunday School curriculum is likely to have been confined to religious instruction such as learning the Commandments and catechism by heart, and that the place of the humble in society was to serve the better-off and to be grateful for any crumbs from the rich man’s table. Though virtually nothing more is known of the school – where it was held or who taught there, or the names of the children who attended it (3) – it is certain that it flourished “though not regularly supported with the same liberality“; total annual subscriptions in the early 1800s averaged twenty-five guineas, but any shortfall in finances was generously met by the Provost and Fellows of Eton College and from their amply-endowed coffers. William Webb, a painter, glazier and plumber, (4) collected subscriptions and paid the accounts.

It was to this institution that Mark Antony Porny bequeathed something over £5,000. His executors, and trustees for the bequest, were Francis Stacey, “grocer to Their Majesties” and Charles Knight, author of Passages from a Working Life, who was himself interested and influential in educational matters; they consulted a Windsor solicitor, John Secker, as to whether the Will was valid. He asked Counsel, whose opinion was that there was no doubt about Porny’s right to dispose of his money, even though an alien (and citizen of a country with which Britain was at war), but that there were difficulties about the school being able to benefit from his generosity because legally it hardly existed. There were “no rules for appointing directors, nor were a treasurer or other officers appointed specially for the management of the charity“. As far as can be made out, an unwieldy committee of the twenty-two principal subscribers was the nearest approach to a board of trustees or governors. Clearly some better system must be established before the funds could be made available, and proceedings in the Court of Chancery were put in train.

These deliberations took some time, but account for only a small fraction of the ten years between Porny’s death and the expansion of the schools (the term ‘schools‘ was always used because of their being both Sunday and day schools, and additionally the boys’ and the girls’ establishments tended to be considered separately). John Shephard, Vicar of Eton from 1875 to 1905 and author of an admirable and scholarly history of the parish (5), states that the long delay was caused by the challenging of the Will by some of Porny’s French relatives; the documents to which I have had access tell nothing of this, but I have no doubt that it is accurate.

It was not until 13 February 1812 that a meeting of “the subscribers at large” was called, with the Provost (now Joseph Goodall) in the chair, to appoint eight men to be Trustees of the Porny Charity. They were John Macqueen, a surgeon; Edward Raguenau, who kept a College boys’ boarding house; Edward Williams, a bookseller; William Cutler, a plumber; John March, a draper; William Hexter, who was “writing master” to College boys and also taught such scant mathematics as those boys had an opportunity to learn; James Rogerson, a cutler; and William Webb, the glazier-cum-painter-cum-plumber who had been in charge of the little school’s funds and who was now to act formally as treasurer, though the cash was henceforth funnelled through the Provost.

Some good at least had come of the long delay, as the money had been invested; so that when the Accountant-General released it in July 1812 there was £9,124.8.4, a little of which seems to have been used to pay off debts of the charity school.

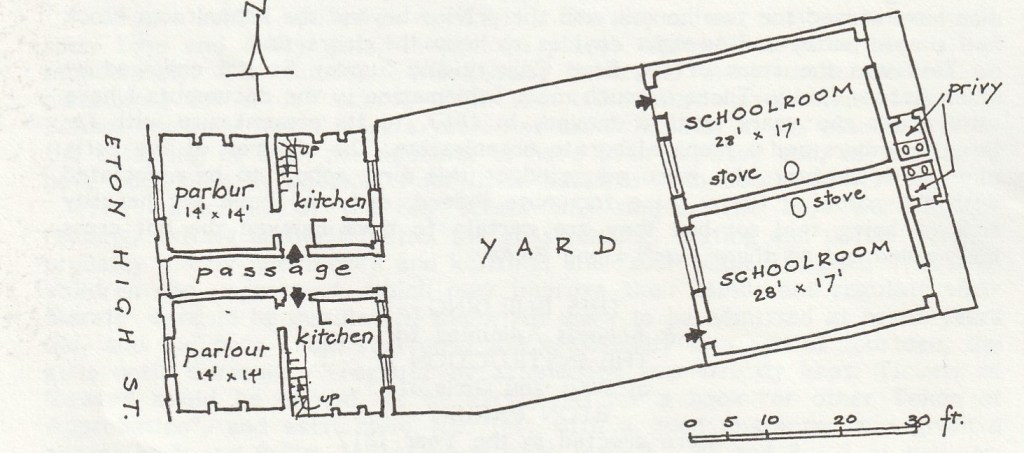

Action now speeded up. The Court of Chancery had, in December 1811, employed two surveyors to draw up a schedule, or specification as it would be called nowadays, and to give an estimate as to how much it would cost to build two schoolrooms 22′ X 31′ each, and two four-roomed houses, one for the master and one for the mistress. They arrived at the figure of £1,273. The site was already decided, as Eton College had agreed to grant for the purpose a forty year lease at £2 a year (6) on the site of 29, High Street, Eton, a most conveniently central position.

It is curiously unclear how the numbers of the children to be educated were arrived at. Three factors must have come into it: the amount of money available, not only to build the fabric but also to act as sufficient capital to generate income with which to pay the teachers and keep the whole. thing going; the size of the site offered by the College; and the number of children who would be eligible for, and want, the schooling. (7) And who would decide how big a room was needed for how many children and on what criteria? Presumably rooms big enough for the day school children only were planned, with the much larger Sunday School continuing wherever it had been held previously.

The Court of Chancery, doubtless on some accepted formula, had had its estimate based on rooms 22′ X 31′; Mr Webb, the treasurer, considered that each would hold a hundred children. The Trustees, however, in May 1812, after tenders had been accepted for this size, had second thoughts and felt that “since the Plan was approved for erecting the Charity Schools, the System of Education adopted by Dr Bell being considered more eligible and being also recommended by our Diocesan” (the Bishop of the diocese, at that time Lincoln) “the Trustees are of the opinion that the schools… are not of sufficient extent… and that Mr John Lane of Windsor be employed to prepare a plan according to this intended alteration and that he do superintend the execution of the same…“

Dr (Andrew) Bell needs some explanation. He was a missionary clergyman in India who had worked out a monitorial system of education to cope with the problem, in Madras, of too few teachers for too many children, and he urged that the same thing was suitable for poor children in this country, running a school in St. Botolph, Aldgate, in the City of London, along those lines. In Bell’s system – also, for obvious reasons, known as the Madras system – the master or mistress taught a group of the brighter children, the monitors, who then passed on what they had learned to about nine others each. It was simplicity itself, and extremely cheap, and when discipline was strict and learning largely by rote, it did actually work.

The National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, understandably more generally called simply ‘the National Society’, was founded in 1811 with the aim of spreading education by means of this monitorial system. It took over the charity schools which the Society for the Promoting of Christian Knowledge had been running since the early eighteenth century, and, having raised a considerable sum of money, was willing to help other schools to set up or develop along the new lines. (At almost exactly the same time the British and Foreign School Society came into being, also using the monitorial idea as developed by Joseph Lancaster; but the British Schools, as they became known, were specifically non-denominational).

The Porny Trustees must have consulted the National Society, on whose criteria the projected classroom size was considered right for eighty rather than a hundred children – an improvement, certainly, but still conjuring up a fairly horrifying picture of crowded benches and unwashed smells. 28′ X 37′ was suggested, but finally two rooms each about 28′ X 17′ were built, for a maximum of sixty day school pupils.

It seems likely that, throughout, there was some confusion as to whether the dimensions discussed were for each room or for the block of two rooms.

While this correspondence and discussion was going on, from March to May 1812, local builders were in April invited to tender on the Court of Chancery’s proposals, Mr R. Tebbott of Windsor being successful with a price of £1,723. (Clearly the Court’s surveyors had been out of touch on building prices locally). The contract document signed in July 1812 between the Trustees and Tebbott is for £1,723, which seems odd as the school building erected by him is a different size from that for which he tendered, though the block of two houses, a more elaborate piece of building, remained as specified. (Fig.2) Certainly £1,723 was what he was paid, the final instalment being in June 1813, after being threatened with legal action in the previous February when he had not completed the work to schedule.

While Tebbott was getting on with the building (see appendix), the National Society was undertaking the organisation of the educational side of the new school. It selected Mr Thomas Marzetti to come to Eton “to form a school on the Madras system“; he was an experienced man who had already done the same thing in Mitcham, and in several places in the West of England under the patronage of Sir Thomas Acland. The letter he brought with him, in August 1812, trusted that he would acquit himself to the satisfaction of his employers; he certainly did so as the Trustees wrote in September 1813 to thank the Secretary of the Society for appointing him, saying that his zeal and his “great attention and pains” were much appreciated. It is not clear how much time he actually spent in Eton, and it must be assumed that he was working with the master and children of the existing charity day school. The master was sent to the National Central School for further instruction, the mistress apparently not.

The new school opened in April 1813. The day school numbers were to be sixty boys and thirty girls, though the places may not all have been filled immediately. The Sunday School must have had many more, and to be considered for a day school place any child must have attended Sunday School regularly for at least a year. For either school, it was essential to be the offspring of Eton parishioners, to have been baptised and, of course, to have been born in wedlock. Poor little bastards – no education for them.

The curriculum of the day school was simple. The boys were taught reading, writing and arithmetic; the girls reading, writing and useful works – probably mostly needlework and knitting; and “such plain Religious Truths as children can understand, which may improve their Minds and regulate their Morals” were to be instilled in them. All were to be admitted at seven years old, and the boys could stay until the remarkably late age of fourteen, the girls until thirteen. A register of attendance was strictly kept. Tickets of Reward could be earned, to be exchanged for a book “or other Token of Approbation“, and each child who left with a good character was given a prayer book and Bible. School hours were long: 8 – 12 and 2 – 5 in summer, 9 – 12 and 1.30 – 4 in winter. Holidays were short, a total of six weeks in the year. Sundays must have seemed as lengthy as any other day, with two long church services compulsory, as well as religious instruction in school; but Saturday was a full holiday. The church attended was the chapel-of-ease built in 1768 for the townspeople, College Chapel being their official parish church, but for various reasons unsatisfactory; the chapel-of-ease was directly on the High Street where the War Memorial garden is now. It may have been partly due to the influx of extra children that a larger chapel was needed, and built in 1819.

The first master, who stayed until retirement twenty-three years later, was John Pope; he was paid £50 a year, rising to £56 in 1816. He had a good house provided, and earned an additional sum, varying around £9 a year, for teaching the children to sing. Mrs Miller, the girls’ mistress, also got her house, and only £36 a year; but she did have fewer pupils, quite apart from being the inferior sex.

The costs of running the school all had to be met from the income made from the residue of Porny’s money, as the National Society’s help was limited to advice. The secretary of the Trustees was paid five guineas a year; the buildings had to be insured, and each year cost a fair sum in maintenance and minor improvements; coal for winter heating was always a significant item; equipment, and a most creditable number of books, had to be bought, all of which however simple tended to wear out. But the endowment was sufficient for all this for many years.

A carpenter’s bill of 1813 which has survived gives some details of the schoolroom fittings. Most economically, old desks and forms were re-used repaired and adapted. It is interesting that many of the ledges on which the children rested their slates and ‘copies’ were on hinged brackets, presumably to give some adaptability of arrangements in the classroom. One of the desks in the boys’ schoolroom was 24′ long. There were several book-cases, some locked, and a large strong table with four drawers with locks, as well as a desk for the master – and, presumably, one for the mistress. Other fittings included hat-racks, and sand tables up to 8′ long; it was by tracing with their forefingers in sand that children learned their letters before graduating to writing on slates. There was a pump, presumably in the yard, which would also have served the two houses; and the privies beyond the schoolroom block had simple pulley-and- weight devices to keep the doors shut.

That was the start of the Eton Charity and Sunday School endowed by Mark Antony Porny. There is much more information in the documents I have used about the years until it moved, in 1863, to its present site with far larger numbers and a more elaborate organisation. The children of the early nineteenth century who were educated at this first school to be associated with the name of Porny were fortunate indeed, and may have got heartily sick of being told so; but they are certain to have enjoyed the hot cross buns doled out to them every Good Friday.

THIS BUILDING

& Schools Adjoining for

THE INSTRUCTION

of Boys and Girls of

ETON PARISH

were erected in the Year 1812

under the Sanction of Chancery

in persuance of the will of

MARK ANTONY PORNY

formerly French Master of

ETON SCHOOL

who Died MAY 2nd 1802

The finely-lettered stone on the High Street front of the houses was, most commendably, revealed recently, after being covered up since, perhaps, 1863 when the school moved (see earlier).

Selina Ballance

Appendix

THE SCHOOL (Fig. 2)

This survives virtually as built. When in 1863 the school moved up the street to the present buildings at 14 High Street, the old rooms were taken over for the use of the parish, at a later date becoming a carpenter’s store, and finally, in 1920 or 1921, the Eton Ex-Servicemen’s Club, which it is today.

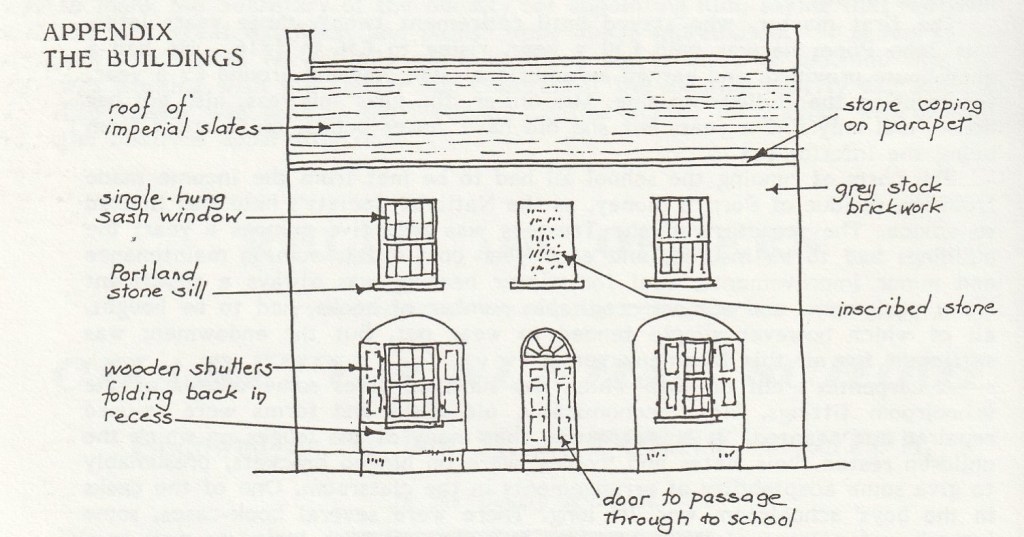

The two rooms (specified as “without any communication with each other“) were, with the privies at the back, the whole building. The walls are 13 1/2” grey stock brick; the hipped low-pitched roof of imperial slates ran down over the privies in a ‘skeeling‘, a term still used in some areas for a sloping ceiling. There is a small lead flat on the top of the roof, through which the stove pipes would have projected. (The grim black cowl still to be seen is of considerable age, but not original). The ceiling was on the underside of the sloping rafters, with open trusses spanning east and west.

THE HOUSES (Figs. 2 and 3)

These also survive in their entirety, though re- planned and added to at different times. Fig. 3 shows their original lay-out, with in each case the only outside door opening off the passage. The doors on to the High Street, with their associated boot-scrapers, and the top storey, were probably all added at the same time in the last third of the nineteenth century. Some of the original York paving stones in the passage and door thresholds survive, as do the Portland stone sills of the windows. The ground floors, though remarkably well-built for the time, with 4″ X 21″ oak joists on sleeper walls and the whole thing ventilated, have been reconstructed, but the original iron vents can still be seen.

Drainage was fairly primitive: a 6″ square brick drain with a stench-trap ran from the kitchens to sluice out the school privies, whence a 9″ pipe ran into the ‘Ditch‘, which doubtless finally found its way to the Thames via a lot of other back premises.

Footnotes

(1) Porny’s Will is interesting in some details unconnected with the bequest to the school. He expressed the wish that his body should lie for a week where he had died “if the weather and the cause of my death admit of it“; then be put in a lead coffin “inclosed in a wooden frame after the manner usually practised“, and that in turn in a “brickt grave” made if possible between two of the buttresses on the south side of St. George’s Chapel. It was to be marked by a black marble tombstone (which is no longer there) inscribed with an appropriate epitaph. The whole Will was written in his “own hand and every page thereto subscribed with both my original and assumed names”. His witnesses were a cyder-merchant and a staymaker.

(2) In A Town Called Eton (Covent Garden Press, 1983) I make the mistake of referring to the 1790 school as a Sunday School only.

(3) In the box in Eton College Muniment Room labelled ‘Porny’s Charity‘, from which most of the information in this article comes, there is one document presumably relating to the 1790 school. It is a printed certificate with the details filled in in MS from the parish of St. Ann, Westminster, stating that Thomas Carter was born on 3 September 1775 and baptised on 12 September. The Certificate, however, was issued on 24 July 1788 when he would have been nearly thirteen years old, and he would have been fifteen by the time the school started. Perhaps it is pure chance that the certificate has ended up in the Porny Charity box; but possibly Thomas Carter may have been not a child but a young teacher at the school in the late 1790s or early 1800s.

(4) Probably the same W. Webb who scratched his name on a window-pane in Election Hall, Eton College – it was a common practise of glaziers after working on a window.

(5) John Shephard, Old Days of Eton Parish, 1908, pp. 49-50.

(6) Not £12 as I state in A Town Called Eton, p. 108.

(7) In 1811 the population of Eton was 2,279.