Published in Windelsora 02 (1983)

© WLHG

When you are only six years old, the fact that the world is in the grip of a war does not seem to be very important. At that age, the prospect of a visit to a garden fete was all I had to think about on one particular day, but because of the war, the events of that day have lived clearly in my memory ever since.

It was Saturday, a fine bright day with blue skies, and the family visited the ICI Paints Division Annual Fete, when it was held on Petersfield, Wexham Road, Slough, a site now occupied by their offices. We had not been there very long before my father and all the other members of the firm’s bowls team went off to play a match at the Alexandra Gardens, Windsor. We stayed on and watched the races. I particularly remember the men’s obstacle race, because some of the barriers looked enormous.

Suddenly some people started pointing. All the sounds of excitement went quiet. The festivities stopped. Everyone was looking up in the sky over the factory. We heard the distinctive sound of a doodlebug and saw it coming towards us. I have a vivid impression of upturned heads. All eyes followed the doodlebug’s progress and there was considerable disquiet as it passed right over us. There was a sigh of relief as it cleared the field, passed over the railway line and went slowly away. Many people went back to the festivities but a few continued to watch as it went in the direction of Windsor. It appeared to get smaller and smaller and then someone realised that the engine could no longer be heard.

The cry went round the field, “It’s stopped! It’s stopped!” It seemed to hang there, waiting, while those around us speculated as to where it might actually be. We generally agreed it was over Windsor. Suddenly it dropped. There was panic all around us.

“My husband’s in Windsor!” screamed one woman. To me, the panic seemed endless. I don’t remember how it resolved itself but my father came home safely. I was not old enough to be told or to enquire further about the incident. I don’t know whether my parents ever found out where the bomb did fall. For many years the memory lay dormant in my mind.

In the mid-70s, I became interested in the local history of Windsor. Everyone else around me seemed to be specialising in something, so I declared that I would specialise in Dedworth because that was where 1 lived. I did receive some polite advice that nothing much was known to have happened in Dedworth – except the flying bomb, that was. The only flying bomb that ever fell on Windsor, fell in Dedworth. Could this be my bomb?

Enquiries showed that it fell at 3.27 pm on 1st July, 1944, and that day was a Saturday. There was very little doubt that this was my bomb, and one of the first two men to go to the rescue was my good friend and colleague, Gordon Cullingham, now Chairman of WLHPG. I am very grateful to him for allowing me to see the handwritten notes he made at the time.

Even though there had been no alert, the first two men had reported to the Rescue Party centre by 3.32 pm, to pick up the National Fire Service report that the bomb had fallen on Kenton’s Lane. In fact, it was the nearby Corporation Refuse Destructor that had received a direct hit. This was indeed fortunate as the Destructor was out of use because of black-out regulations. No one was killed and only one old lady was taken away by ambulance. She was suffering from shock rather than any physical damage. Sixty people were hurt, mostly by flying glass; 24 of these were classed as serious but they were all dealt with at the nearby Warden’s Emergency First Aid Centre.

After ascertaining that no one was trapped, the rescue team began to assess the damage to the buildings. Over 350 houses were damaged, 12 of these seriously. The roads worst affected were Dedworth Road, Kentons Lane, Sheepcote Road and Church Terrace. Repair work had begun by 4.30 pm and members of the Fire Service, the Rescue parties and local builders worked until 10 pm, replacing tiles on roofs. The situation was bad enough for a Regional Rescue Column to assist. This arrived at 6pm and stayed for nearly two days. They supplied 75 tarpaulins which proved essential to cover roofs as the following day was punctuated with heavy showers. Several houses were still uninhabitable, and furniture was removed to various sites in Windsor and Eton. One of the big problems in repairing the houses was the shortage of glass or any other transparent material to cover the broken windows, but all the houses were protected by the following Tuesday. The remains of the chimney of the Refuse Destructor was later demolished and the site cleared.

Dedworth’s All Saints Church was shaken by the blast and this contributed to it becoming unsafe and it was pulled down 20 years later. The present Church Centre was built to replace it and I attended the dedication service on 9th June, 1973.

The site where the bomb fell was eventually cleared and grassed over and is now known as Greenacre.

Pamela Marson

Addendum:

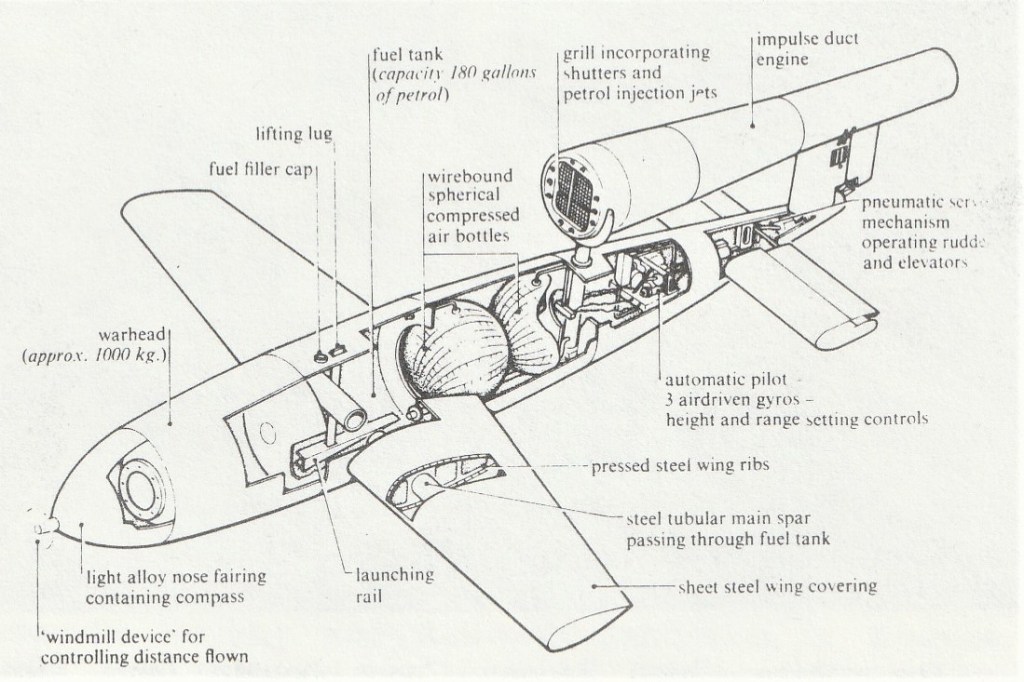

The first doodlebug arrived in June 1944 and the government term was ‘pilotless aircraft’ which soon became ‘flying bomb‘ – people were used to bombs, but not to robots. The RAF talked about ‘doodlebugs‘ and this nickname was accepted by the public. The sound, like a maddened motorbike, was spine chilling, the silence was worse. There were three Rescue parties of 10 men and a lorry and driver based at the Corporation Depot, 16, Alma Road, the Refuse Destructor and the Baths railway arches. Damaged roofs and windows were protected initially by tarpaulins and roofing felt making rooms very dark. Eventually the ration became one transparent pane per room. Old picture frame glass was used by handymen to glaze damaged windows.

Gordon Cullingham.