Published in Windlesora 16 (1998)

© WLHG

Very early in the morning of Monday May 6th 1826, the gates of the Infantry Barracks on Sheet Street in New Windsor opened, and out marched the first battalion of the Scots Guards on their way to London, after doing garrison duty in Windsor for three months. Behind the column of marching men came the baggage wagons, the women and children and the civilian sutlers and suppliers which followed every regiment in those days. Some way behind, hurrying as best as they could and with their meagre bundles hastily packed, came the women and children of soldiers, who lived ‘off the strength’(1). A bugle call, audible throughout the town in the still morning air, had alerted them to the facts that the regiment was on the move. A bugle call they had anticipated ever since their husbands had been confined to barracks a few days before.

This curious procession wound its way up Sheet Street into Park Street, past Frogmore, on towards Old Windsor and Staines and on to London, but few Windsorians, who were about on early business, gave them a second glance. It was a sight they were quite accustomed to. Several times a year regiments would march in or out of one of the two barracks. Only if the bands played, they would stop and listen. Military bands were a popular diversion in the town. The highlight of the week for many was to listen to the bands on a Sunday afternoon in the park or on the Terrace. This time the bands were silent, as it was so early.

However, a few hours later the strains of military music coming from the Old Windsor Road heralded the arrival of the new regiment. This always attracted a crowd of curious onlookers who wanted to see the new tenants of the barracks. Landlords of cheap lodgings in George Street, Bier Lane, Clewer Lane or Prospect Place were ready to welcome new lodgers in the form of women and children ‘off the strength’, even though they could barely afford the few pence for a single room which was too often small, dark and damp.

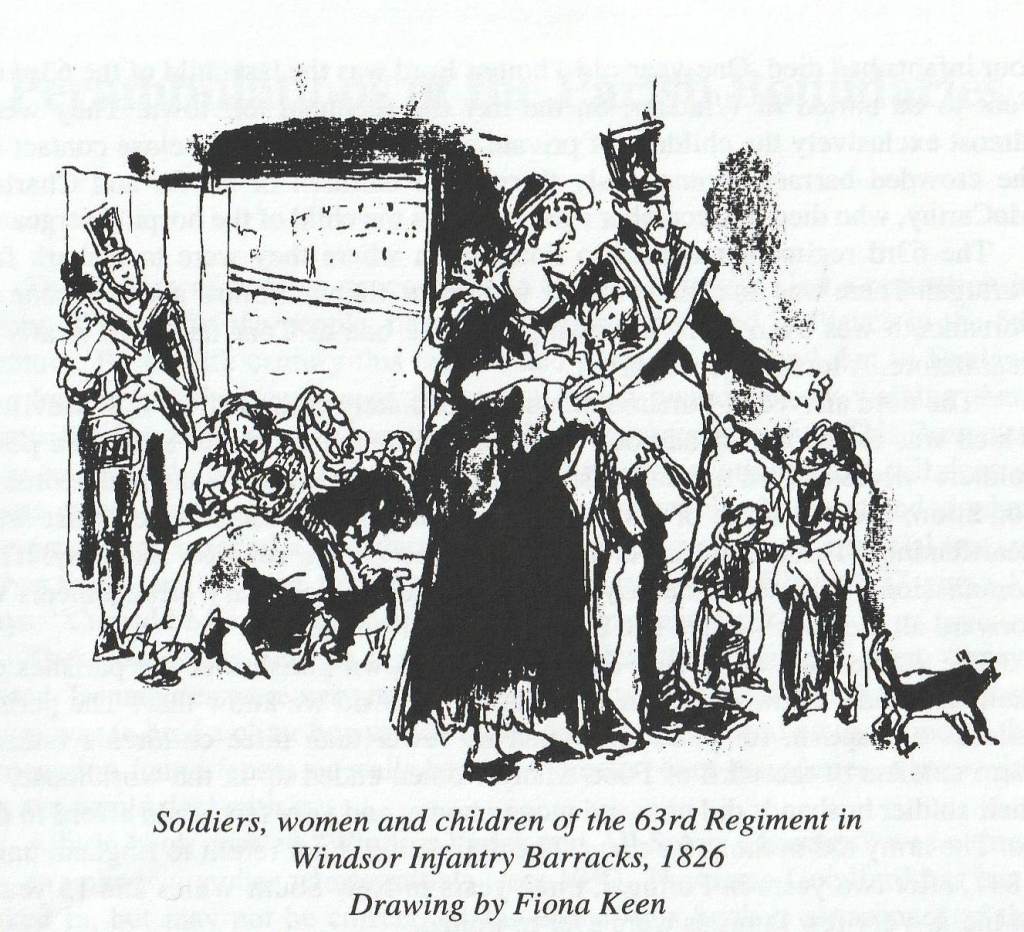

The soldiers who arrived in Windsor on this day belonged to the 63rd of Foot (2), an infantry regiment of the line, not one of the proud Guards regiments Windsorians were used to. They had marched from Chatham, with two overnight stops in London and Staines, where they had been quartered in pubs and inns. What Windsorians noted immediately was, that an unusually large number of women and children accompanied this regiment. Many of the women were pregnant, and there were over one hundred babes in arms, some looking very poorly.

Within the next two days, 749 soldiers and about 400 women and children crowded into the barracks, where they shared quarters designed for 790 rank and file. Privacy was an unknown commodity in the barrack rooms. A blanket hung around the bed, was the only seclusion a family could get. Each room was home to 29 soldiers, besides the women and children. Here they washed and cooked, ate their meals and cleaned their kits, here they gambled, drunk and swore, and here the women bore their babies and the children died. With this sort of intimacy perhaps no one cared that the privies had no doors!

What surprised the landlords of Windsor’s cheap accommodation was that very few families looked for lodgings in the town. The crowded conditions in the barracks should have caused concern in Windsor, but no-one interfered in military matters. That was the business of Horse Guards. And nothing was done when the children started dying.

We need to look briefly at the recent history of the regiment to get a better picture. The 63rd of Foot had been stationed in Ireland between 1820 and 1826. Like most British regiments who had spent some time in Ireland, they had become ‘very much married’; they had also taken on many Irish recruits, 182 during the last year alone. In March 1826 they were ordered back to England, first to their depot in Chatham where they would be kitted out and then on to Windsor. As they marched from Castlebar to Cork for embarkation, they were followed by another army of some 400 wives, women and otherwise with a countless number of children.

At Cork there ensued battle royal. It was against regulations for a regiment to have so many women on the strength. In Ireland military authorities turned a blind eye to what was going on, but in England it was going to be another matter. Therefore 300 women would have to stay behind and what became of these women was not the army’s concern. What happened at Cork on March 25th 1825, no one will ever know, but going by other reports of such departures, it must have been a heartrending scene. Wailing and pleading women clinging to their husbands and begging to be let on board, lest they should be left destitute, sobbing children sitting on little bundles of belongings not knowing what was to happen to them. Lots were drawn to determine who could board the ship and who was to stay behind. This was always done just before embarkation, so that married soldiers would not be tempted to desert. Only six women per company were allowed to go. However, the women of the 63rd were more resourceful, they refused to let their lives be decided by a lottery. Somehow, either as stowaways or on another ship that sailed to Portsmouth and then to Chatham the majority managed to follow their soldier husbands or sweethearts to England. By the time the regiment marched to Windsor, this extra ‘baggage’ of women and children was still with them.

I don’t know when the dying started. Maybe a number of children had already died on the long arduous march, but on May 10th, one-year-old James Groves was buried at Windsor. Another child, ten-month-old Elizabeth Holden died on May 25th. The next day Jane, wife of Patrick Smith, died aged 38. Both their children, Jane and Patrick were to follow their mother two months later. In June, 12 children died, the oldest barely two years old. William Key and his wife lost their twins within a week and Patrick Malony and his wife lost two of their children within a few days. During July there were 14 deaths and in August the death toll rose to 32, none were more than 3 years old.

By now the plight of the children of the 63rd regiment had become known in the town, but there is no evidence of the usual collection or subscription list to raise money for the needy, that Windsor was justly proud of. Instead, on August 26th the local newspaper published a report about the tragedy, which was sandwiched between two articles about Egham races:

“We perceive by the advertisement that the theatre will be open every evening during the Egham Races.“

“We very much regret to state that a serious fever has during the past few weeks prevailed amongst the children belonging to the 63rd Regiment, in the barracks at Windsor. A disproportionate number of women, some of whom were unmarried, accompanied the regiment from Ireland; and, in consequence of the non admission of a part of that number into barracks, many scenes of misery have occurred in this town, and a considerable burden has been entailed upon the inhabitants. It has further lessened, in consequence of the unfortunate disease which prevails among these poor children; and considerable alarm has in consequence been felt by the inhabitants, that our own population, which is sufficiently crowded, may be thus exposed to a fearful contagion. We trust that these alarms are unfounded; and that a proper representation at the Horse Guards will show the necessity of some accommodation being extended to the suffering families, so as to lessen the misery and inconvenience of their being crowded in barracks, without throwing them still further upon parochial relief, with the chance of spreading disease amongst the community in general.

“It gives us great pleasure to learn that the inhabitants of Windsor have subscribed to a Silver Cup of 50 sovereigns value towards the sport of Egham Races…”

It seems that although everyone felt sorry for the children, there was nothing they could do for them. Perhaps the fever had swept through the town and most people were too much concerned with their own sorrow. The child mortality had indeed been very high in Windsor during the last three years, rising from 49 in 1823 to 73 in 1824. There was a slight reduction to 71 in 1825 and to 70 in 1826. Not until 1827 did it fall again to 50. One cannot rule out that there had been a virulent fever in the town, possibly scarlet fever or diphtheria, although there is no mention of it in the newspapers. Many of their deaths occurred in streets like Bier Lane, George Street and Clewer Lane, areas where families ‘off the strength’ usually found cheap lodgings. However, parish records reveal that in 1826 fewer army families than usually lived in the town. The 16 children of the 63rd regiment who were baptised in Windsor Parish Church all lodged in the barracks. Even unmarried mother Bridget Thompson gave her address as Infantry Barracks when her son Richard was baptised in June. Of the 40 children baptised at the Catholic Chapel in Hermitage Lane, 27 belonged to the regiment. This register does not give addresses, but five families who suffered subsequent bereavements, all lived in the barracks.

Families who followed regiments to Windsor had always managed to find lodgings. Was it that because of the fever, the families of the 63rd were not welcome there? Or was it because most of the women were Irish and many were not married? Perhaps they simply could not afford to pay for lodgings. Thus, contrary to what the papers said, the majority of soldiers’ families, married or otherwise, were crowded into the barracks, where the fever spread like wildfire and the children continued to die. Neither army authorities, nor the Windsor parish seemed to have made any effort to help them, nor did the newspaper mention their plight again.

In September the death toll dropped to 11, among these was John Evans, who had been baptised in the Windsor parish church just two weeks previously. On 16th of this month the regiment was inspected by Major General Sir Henry Torrens who commented on the cleanliness and soldier-like appearance of ‘this fine body of men’. No mention was made that children were still dying in the barrack rooms, that 22 soldiers had deserted and six had died since the regiment came to Windsor.

In October the death toll dropped to five, but rose again to ten in November, when for the first time the children were a little older, that is between two and four. Finally on December 20th, the regiment left Windsor, but not before another four infants had died. One-year-old Thomas Ford was the last child of the 63rd of Foot to be buried in Windsor, on the day the regiment left town. They were almost exclusively the children of private soldiers, who lived in close contact in the crowded barrack rooms. Only three were children of NCOs and Charles McCarthy, who died in December aged two, was the child of the hospital sergeant.

The 63rd regiment marched to Portsmouth where they were to embark for Portugal. There was no chance for the women to hitch a lift now and the scene at Portsmouth was even more harrowing than the one at Cork had been nearly a year before. A local paper reported:

“The 63rd arrived at Portsmouth and immediately embarked on the ‘Meville’ which was towed out of harbour on Sunday morning by steam boat. The poor soldiers’ wives arrived in hundreds, having marched 26 miles a day in deplorable condition; and the scene of distress at witnessing their husbands departure was heartrending. Three children died from fatigue on the road on Saturday. The commissioner and Sir James Lyons have made the necessary arrangements to forward all the poor women and children to their homes.”

The women and children were sent to their own parishes or the parishes of their husbands, a few remained in Windsor. How do we know that? The parish records of baptism for 1827 show that no fewer than three children’s fathers were soldiers of the 63rd of Foot. Many women ended up in the workhouse, if their soldier husbands did not send money home, and very few could afford to do so. The army did nothing for them. The regiment did not return to England until 1847, after two years in Portugal, three years in New South Wales and 15 years in India. Very few families were ever re-united.

Birgitte Mitchell

Birgitte Mitchell has lived in the Windsor area for 27 years. She trained as a teacher at Reading University and gained an honours degree with the Open University. At present she is working on a thesis: “Problems of a garrison town; Windsor during the early nineteenth century”, a project she has been working on for some years.

(Web Editor note July 2023: The author of this fascinating story, Brigitte Mitchell is currently chair of the WLHG)

Notes

(1 ) When a soldier wanted to get married, he needed permission from the commanding officer to bring his wife ‘on the strength’. She could then share her husband’s bed in the corner of a barrack room. Leave to marry was granted to soldiers with good character after 7 years service. As only 6 women for every 100 men were officially allowed on the strength, many soldiers married without permission. These women had to live ‘off the strength’ and were not recognised by the army as wives of soldiers.

(2) After 1881 it was known as the Manchester Regiment

Sources

Windsor and Eton Express Newspaper files for 1826, Slough Library

Muster book of the 63rd Regiment 1826 PRO, WO 12 7259

Records of burial of St John the Baptist Church, New Windsor BRO D/P 149 1/26

Records of baptism of St John the Baptist Church , New Windsor BRO D/P 149 1/17