Published in Windlesora 19 (2002)

© WLHG

The year of Jubilee is come,

Sound, sound the trumpet, beat the drum,

Extend its joys from shore to shore,

Open wide the prison door.

The day of Jubilee proclaim,

In honour of King George’s name.

George III was the first king whose reign of 50 years was celebrated in towns and villages nationwide, though it wasn’t called ‘Golden’ but known simply as ‘The Jubilee’. The word originates in the Jewish law of the Old Testament where it refers to the annulment of debt after 50 years, and the King matched this tradition by giving £3,000 from his own purse for the release of Crown debtors from jail (by no means the general amnesty suggested by the song). The Jubilee was also celebrated twice, principally on Wednesday 25th October 1809, the day when the King entered into the fiftieth year of his reign, and then again a year later — though more mutedly — when despite age and infirmity he completed his half-century as monarch. Yet because of this frailty, half-blind and half-deaf, the King himself took almost no part in any festivity in either year.

The country, however, was very willing to celebrate, and indeed in 1809 people desperately needed something to cheer about. The war with Napoleon was dragging on, raising prices and taxes, and Britain had had no great success since the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Charles Knight recalls how the sturdy son of a joiner returned to Windsor ‘crippled and emaciated’ from the fighting, a visible reminder of the realities of war. For the royal family there had been great embarrassment earlier that year when charges were laid in the House of Commons against Frederick Duke of York, the King’s second son and Commander-in-Chief of the army. He was accused of improperly giving promotion to men who had bribed his former mistress, Mary Anne Clarke, to recommend them to him. Though it was not proved that the Duke knew of these bribes, he felt obliged to resign.

But in contrast to his wayward sons, the 71-year-old King, temperate and God-fearing, was immensely popular, and nowhere more so than in Windsor. From 1778 it had been the principal place of residence for himself, Queen Charlotte, and their six daughters, Charlotte, Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary, Sophia and Amelia. For 30 years he had not only dealt generously with the town, but had earned a reputation for affability, remembering people’s names and taking a good-humoured interest in their affairs. Everyone was welcome on the South Terrace on summer Sunday evenings when a band played and the King walked with his family, chatting to all and sundry. There is a caricature Jubilee portrait, dated 1st October 1810, which shows him red-faced and tubby, walking with a stick on the terrace. With his broad-brimmed hat (to shield his weak eyes) and simple coat he looks more country gentleman than king, and indeed he had been mockingly nicknamed the Squire of Windsor, or Gentleman George, for his love of hunting and farming. But though he had his fads and foibles his unworldliness was endearing. Once, for example, while visiting his stables he came upon Daniel Smith, manager of his prized flock of merino sheep, who was gazing at what was left of his house after a fire. The King suggested that in rebuilding it an external wall should be carried a few feet further out. Smith demurred, pointing out that this would encroach on his Majesty’s own land. “What!” exclaimed the King. ‘Did you think, Smith I was so bad a neighbour? Take it, take it!’

So for the Jubilee the town exerted itself to show affection and respect. A grand triumphal arch was built across the High Street, from the Castle Inn to the Guildhall, and decorated with images of the King and Queen, figures representing the four seasons and various other devices, all painted ‘in transparent colours’ by Matthew Wyatt. On one side ran the inscription ‘God Save the King’ and on the other ‘King and Constitution’. A second arch in Sheet Lane (Street) was paid for by the carpenter to Windsor’s Board of Works, a Mr Tibbett. It must have looked spectacular at night, for it was illuminated by ‘exactly’ 2,000 lamps (how long did it take to light them?) Many shops were decorated, and the Guildhall itself was adorned with lamps and transparencies, pictures on loyal themes which were lit from behind to create a stained-glass effect.

The celebrations on 25th October began at break of a day which was luckily to prove fine. At 6 am the town was roused by a fanfare of trumpets; church bells rang out and drums beat to arms as the Royal Horse Guards Blue, the Staffordshire Militia and the Windsor and Clewer Volunteers went on parade. No doubt many of the watching citizens wore one of the popular Garter blue ribbons with a medallion of the King’s head. At eight o’clock when a service of thanksgiving was held in St George’s Chapel almost everyone was dressed in Garter blue. The King was said to be in cheerful mood, but this was the only event which he attended himself and even then his thoughts and prayers were probably more for his beloved youngest daughter than for himself. Twenty-six year old Princess Amelia was suffering from tuberculosis and was in Weymouth with Princess Mary, in the hope that sea air might restore her health. The eldest princess was married and living abroad, but Princesses Augusta, Elizabeth and Sophia were there, along with their brothers the Dukes of York, Cumberland, Kent and Sussex (Edward Duke of Kent, fifth in line for the throne, could never have dreamt that one day a daughter of his would celebrate a Golden Jubilee). After the service the Queen and Princess Elizabeth drove out from the Castle between lines of the Horse Guards, passing under the triumphal arch on their way to Frogmore to inspect the preparations for the evening’s festivities. But by mid-morning they had returned, ready for the whole party — minus the King — to attend the ox-roast on Bachelors’ Acre, where crowds were waiting excitedly for them.

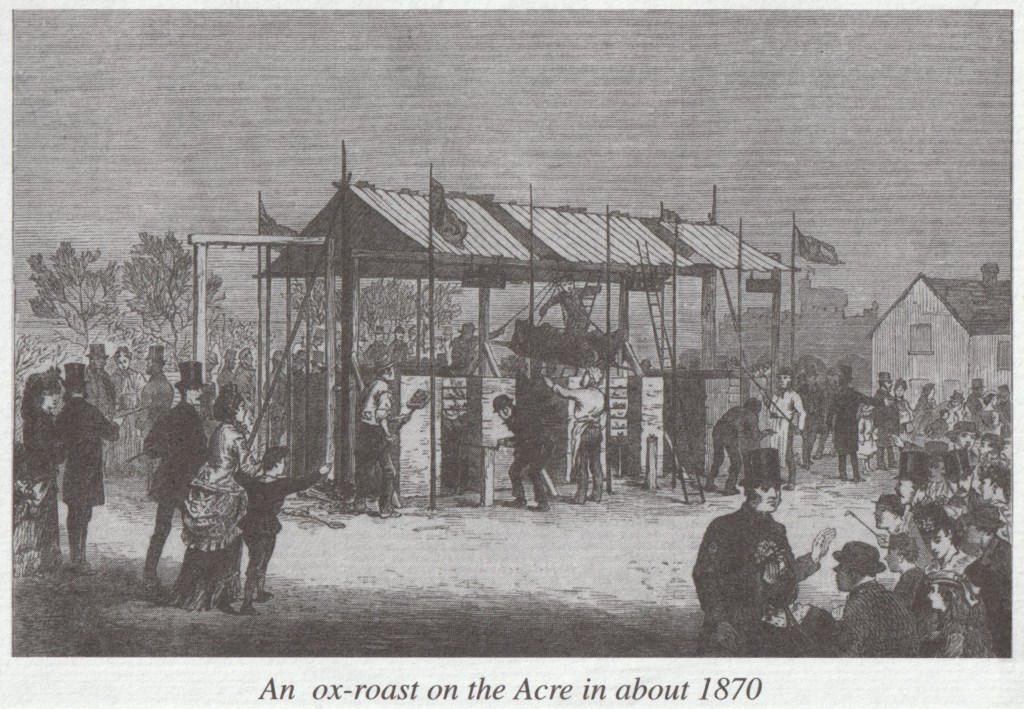

The Acre is the place where in ancient times butts were set up for archery practice, once compulsory for men and boys over seven years old — maybe that is how the word ‘bachelors’ became attached to the piece of land. But the men who formed the Society of Bachelors around 1761 were certainly not all unmarried. It was an association perhaps like a modern Rotary club, and in 1809 leading citizens like the Charles Knights, father and son, were members. However, the Acre itself was in no fit state to host a royal occasion, degraded by the seepage of privies belonging to the houses above it, and from the custom of holding bull-baitings there. So the Bachelors set about cleansing the site, filling in the stinking pools and channels. Then they could build their giant barbecue, a brick construction large enough to roast two sheep as well as the ox on its grills. This animal was the gift of a wealthy 23-year-old member of the Horse Guards, 2nd Lt Robert Orde Fenwick.* The Bachelors themselves provided plum puddings to follow: 100 eggs, 120 Ibs of plums and 28 Ibs of currants went into their making. Fires were lit the day before and the roasting went on all night.

At one o’clock 50 pieces of cannon were discharged from Windsor Park, just as Queen Charlotte, leaning on the arm of the Duke of York, with other royal dukes, princesses and attendants, were met by the Mayor, Edward Bovingdon, and the rest of the Corporation. Carrying white wands of office they accompanied the party to a house overlooking the Acre whose owner, Colonel Buckeridge, had had his garden carpeted and a stand built for their reception. After viewing the scene the Queen and her family moved down into the Acre itself where 50 of the Bachelors greeted them, dressed in blue coats, white waistcoats, knee-breeches, and silk stockings. Even the butchers acting as cooks sported blue frocks and silk stockings. The royal party duly admired the cooking arrangements, and were presented with Slices of the meat on silver dishes. All ‘appeared highly pleased with the novelty’ (Reading Mercury). A taste of the plum puddings was followed by ‘an elegant collation’ served in Colonel Buckeridge’s marquee. When the visitors departed it was to rousing cheers.

Apart from the King, another notable member of the royal family was missingfrom the ox-roast: George, Prince of Wales, the future George IV. He and his thirteen-year-old daughter Princess Charlotte had arrived in Windsor at half-past twelve, but the unpopular Prince tended to shun public events, though the little Princess would probably have enjoyed it. However both they and the Duke of Clarence, the future William IV, were present at the féte which Queen Charlotte had commanded for Frogmore that evening. The house with its gardens had become a refuge for her from the stresses of her husband’s illnesses; with the help of Princess Elizabeth, the most artistic of her daughters, it had been beautifully furnished and the Princess had also played a leading part in planning her mother’s Jubilee evening.

For those lucky enough to be among the 1300 of the local nobility and gentry invited it proved a magical occasion. The gates were thrown open at 9.30 pm and guests then made their ways along paths illuminated by coloured lanterns hanging in the trees. On the main lawn hot-house plants were banked up, and there were marquees to serve tea and coffee. The Queen and her party, the ladies in white satin, arrived at ten o’clock, signalling the start of a firework display. A stroke of theatre followed when suddenly there appeared ‘on a beautiful piece of water opposite the garden front of the house, two triumphal cars, drawn by two seahorses each, one occupied by Neptune, and preceded by the other with a band of music’ (Reading Mercury). As they approached a bridge built for the occasion it lit up, displaying the words ‘Rule Britannia — Britannia rules the Seas’, whereupon the band struck up the tune. There were more scenic effects, including an ‘elegant Grecian temple’ created on the mount (where Victoria was to build her mother’s mausoleum), its interior lined with purple, and at its centre ‘a large transparency of the Eye of Providence, fixed as it were, upon a beautiful portrait of his majesty, surmounted by stars of lamps’. On the double staircase which wound down to the water altars burnt incense which scented the air. Guests wandered in the fairy-tale scene until midnight when a supper was served, the townspeople dining in Frogmore’s upper rooms.

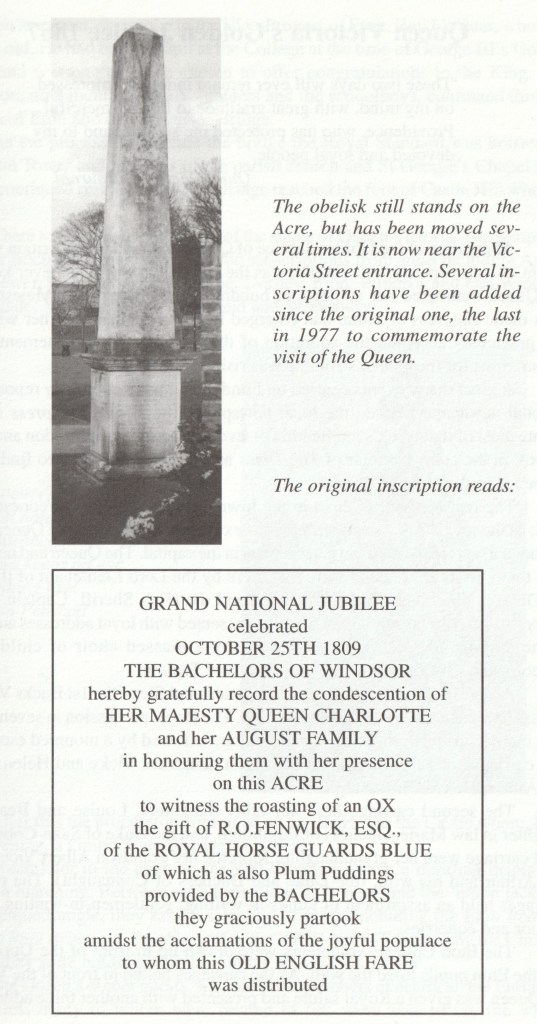

Next day coarser tastes were indulged with a bull-baiting, and there was a dinner at their barracks for the men, wives and children of the Staffordshire Militia (which had been serving in Windsor for a number of years). The Jubilee ended with a ball for the townspeople at the Guildhall. Here class prevailed, Charles Knight satirically recalling the ‘silken rope’ which divided the dance floor, separating the ‘attorneys’ wives and daughters from the grocers’ wives and daughters’. He declared that the tradesmen’s8 daughters were by far the prettier! And so the fun was over. But so proud were the Bachelors of their event that the following year they commemorated it by erecting and inscribing an obelisk of Portland stone in the middle of the Acre.

On 25th October 1810 church bells nationwide rang out again to celebrate the completion of the 50th year of the reign — but not in Windsor. In a house in St Albans Street just behind the parish church Princess Amelia lay dying, having borne months of pain courageously and with resignation to the will of God. But the King could not resign himself to losing his daughter and ironically 25th October was almost the final day of his exercise of the powers of monarchy. On 26th October he dictated his last official letter; next day his mental condition became very alarming. He was gripped by the madness (really the metabolic disease called porphyria) which had afflicted him periodically ever since 1788 and from which, this time, he was to make no recovery.

In the following year the Prince of Wales became Prince Regent and George III’s rule was over. Except that he did not die but lived on in a suite of rooms on the north side of the Castle until 29th January 1820, in the 60th year of his inheritance of the throne. By his last years he had become generally calm and seemingly contented, sometimes playing the harpsichord, sometimes engaging in conversations with men long gone, sometimes speaking of himself as if dead too, and wearing mourning, he said, ‘in memory of George III, for he was a good man’. It was a sentiment with which the 30,000 subjects who flooded into Windsor for his funeral would concur.

Hester Davenport

Notes

* Fenwick had bought his commission the previous year, and in January 1810 spent a further 2,500 guineas on promotion. But in 1812 he retired, never having seen active service. He had, however, acquired a kind of immortality with his name engraved on the Bachelors’ Acre obelisk.

Bibliography

Aspinall, A, The Later Correspondence of George III, 1808-1810, Cambridge

University Press, 1970

Annual Register for 1809

The Gentlemans Magazine for 1809 and 1810

Hedley, Olwen, Round and About Windsor and District, Oxley & Son Ltd, 1948

Hibbert, Christopher, George III: A Personal History, Viking, 1998

Knight, Charles, Passages of a Working Life during Half a Century, Bradbury & Evans, 1864

Knight, Cornelia, The Autobiography of Cornelia Knight, edited by Roger Fulford, William Kimber & Co. Limited, 1960

Reading Mercury for 30 October 1809 and 25 October 1810

Taylor, Joseph, Relics of Royalty, AK Newman & Co., 1820

Tighe, Robert Richard, and Davis, James Edward, Annals of Windsor, Longman et al, 1858

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank Mrs J Kelsey, Deputy Registrar of The Royal Archives, Brigitte Mitchell, and the Household Cavalry Museum, for information supplied.