Published in Windlesora 28 (2012)

©2012, WLHG

One of the most enduring images from Olympic Games of the past is of the Marathon of 1908 and the frail, tottering figure of Dorando Pietri of Italy, dwarfed by officials as he dazedly staggers towards the tape, falling, being helped to his feet, falling again as his lips move with some repeated mantra. When he finally made it over the line to wild cheers he collapsed unconscious. But because he had been helped to stand the Americans lodged a protest and their own runner, John Hayes, was declared the winner. (Dorando’s time was 2 hours 54 minutes 46 seconds, with Hayes half a minute behind – about half an hour slower than a marathon today).

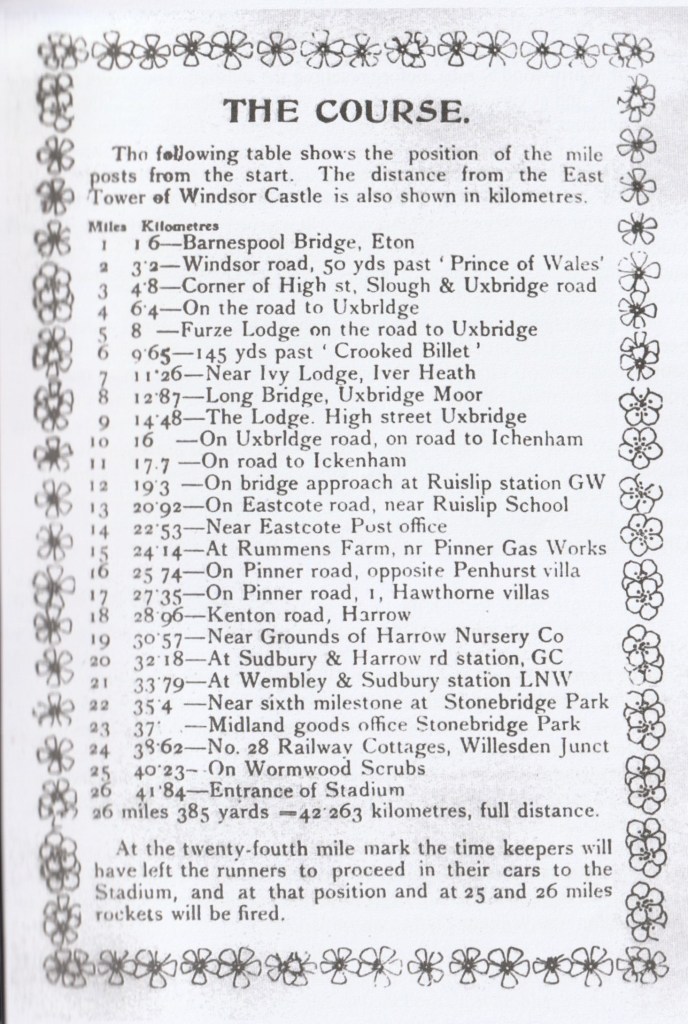

The race had started from Windsor Castle, ending at the White City stadium, thus creating the marathon distance, 26 miles 385 yards, which is still Fun today. Ironically, if the race had been of 25 miles, the distance of the three earlier games, Pietri would have won with ease. Moreover, the Olympics shouldn’t have been in England at all, but in his native Italy (where he was a confectioner by trade). But when Vesuvius erupted in 1906 Italian resources were too stretched to stage the games, and so they came to this country.

A moving spirit behind this decision was William Grenfell, Lord Desborough, who lived at Taplow Court. He was immensely tall (6ft 5 ins) and an astonishing sportsman – cricketer, athlete, fencer, rower, wrestler, swimmer, horseman, mountaineer, fisherman. Desborough led an appeal in the funds which was so successful that more was raised than was needed. He was energetic in the creation of the White City stadium where the games were held, the name derived from the marble used for the Franco-British exhibition which he had been instrumental in staging earlier that year. And it was Desborough who organised the start of the marathon at Windsor Castle, on Friday 21 July.

There was great excitement in the town and the streets were decked with bunting. A few of the runners arrived in advance and stayed overnight, including the Canadian Indian, Tom Longboat, who was one of the favourites. He stayed at the White Hart inn and on the previous day was taken on a tour of the Castle. Asked what he thought of it he expressed suitable admiration but joked that he was glad he didn’t have to run in armour, with ‘tin cans’ hanging round him. Other runners arrived by train next day, where a room in Central Station had been set aside for their preparations and medical examinations.

Although the weather for these Games was in general poor, on the day of the Marathon it was perfect, at least for the spectators. For the runners, it was rather too warm at 80° Fahrenheit. Businesses in Windsor closed for the day, and schoolchildren were given time off to watch the start, with space allotted to them by King Edward VII under the Curfew Tower. There was a civic lunch for Lord Desborough and other dignatories hosted by the Mayor at Windsor’s leading restaurant, Layton’s, in the station approach.

The race was due to start at 2.30 pm, near the East Terrace and some 700 yards from Queen Victoria’s statue. Six red upholstered chairs were set out for members of the royal family. A pamphlet published in Windsor for the event says that the King would start the race but in fact it was the Princess of Wales (later Queen Mary) who arrived at 2.15 in her carriage wearing a white dress with blue flowers. She was accompanied by Princess Mary and Princes Albert and Henry, while nurses brought the young Princes George and John (aged six and three) wearing sailor suits. A draw for positions had taken place and the 55 starters from 16 countries made ready in four rows. Lord Desborough stood in his car behind the runners, starting pistol in hand, waiting for the signal. When all was ready the Princess of Wales pressed a button on the table in front of her which communicated directly to Lord Desborough. At 2.33 precisely he fired the pistol and the race was off: in the words of the Windsor Express, ‘moving all together like a regiment of soldiers at the order to march the clump of lightly-clad humanity passed from rest to rapid motion‘.

A roar of cheering greeted the athletes as they swept down Castle Hill and then turned right onto the cobbles of Thames Street (which are visible in the picture below). It was gratifying to see the British runners in the lead, though they were not to stay ahead. Once the athletes had disappeared excited Windsorians were able to follow the course of the race by telegrams posted in the window of the Express newspaper, whose offices were then at 4 High Street.

The route to the stadium took the runners over Windsor Bridge and through Eton, then to Slough, Uxbridge, Ruislip, Pinner, Harrow and past the prison of Wormwood Scrubs, before reaching the stadium. They were followed by cyclists, and at various points were able to have drinks: it was claimed that Tom Longboat, the leader for much of the way, drank a bottle of champagne. I so it did not help his chances, and after several attempts Pietri was able to overtake him. But the last part of the route was hilly and Pietri arrived exhausted at the stadium. It proved later that the words he mouthed to himself over and over were ‘Vincero o moriro‘ – I’ll win or I’ll die. He nearly did, and indeed there was a rumour in the evening that ‘Dorando is dead’. He was not, and the next day Queen Alexandra, who had watched the end of the race in anxiety, presented him with a special gold cup.

As with the Marathon, the 1908 games established patterns which have been followed ever since. Lord Desborough himself derived a great deal of satisfaction from his efforts, believing that the coming together of so many young men from so many countries would contribute to future world peace. Alas, he was wrong and the First World War was to deprive him cruelly of two of his three sons, one of them the poet Julian Grenfell (his third son died tragically too, in a road accident, leaving him without an heir). But summer 1908 seemed a golden period, literally so for the host nation which won 56 gold medals and topped the medals table for the only time – to date – in Olympic history.

Hester Davenport

Sources

Windsor Express 24 July and 1 August 1908

There are numerous sites devoted to Dorando Pietri, who became an international celebrity: he made a considerable sum of money, and thereafter never lost a race, beating Hayes several times.

You can see the film of the race on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HUpW6blZLyQ

This short film (in Italian) shows the start at Windsor and ends with Queen Alexandra presenting Pietri with the gold cup (thanks to Elias Kupfermann for this information).

The first placed Briton was William Clarke, who was 12th.