Published in Windlesora 25 (2009)

© WLHG

As Britain changed from a largely agricultural nation to an industrial powerhouse between 1750 and 1850, a new professional class of engineers appeared. The navigations, roads, railways and associated bridges, tunnels and other infrastructure which revolutionised transport were products of their fertile minds. Often self taught — there was little previous knowledge to fall back on – these pioneers embarked on stupendous projects, building with manual labour alone structures which would still be found challenging todaay. Furthermore much of what they achieved remains with us, not as historical artefacts, but in revenue earning services.

With few exceptions the names of these pioneers are largely forgotten. Watt, Stephenson and Brunel may still make the history books but many of the great 19th century engineers are known only to those with a special mterest in their work.

Once such was Daniel Gooch, resident of Clewer Park in Windsor, who not only served the Great Western Railway for much of his working life but as instrumental in laying the first transatlantic cable with the with the help of Brunel’s great ship, the Great Eastern.

From the outset, the role of Locomotive Superintendent was to prove an onerous one. Gooch wryly remarks in his memoirs of the time:

One feature of Mr Brunel’s character (and it is one which gave him a great deal of extra and unnecessary work) was that he fancied no-one could do anything but himself.

This included the designing of locomotives and, however good his skills in surveying, bridge building, and station design, Brunel’s engines were almost useless. Gooch surveyed his charges with horror. Brunel has laid down strict design criteria to the builders which meant that the machines could hardly drag themselves along let alone a train. However Gooch saved the day by obtaining an engine from Robert Stephenson which was destined for the New Orleans Railway. It was a fortunate purchase, as the North Star proved the most satisfactory of the stud of locomotives available. It was quickly followed by others to the same design.

Arrangements for the delivery of the new locomotives showed how difficult Brunel could be to work with. The first two engines came by canal to West Drayton and while his boss was busy designing a special rig to swing them out onto the canal-side, Gooch proceeded with the equipment available and had the engines unloaded and transferred to the engine shed at West Drayton. Brunel was most displeased that the work had been done without him and issued a severe reprimand. Thus, when the North Star arrived by river at Maidenhead, Brunel took charge of the unloading whilst Daniel busied himself elsewhere. Through a misunderstanding, a rope supporting the ar legs was released and these fell, killing one man and narrowly missing Brunel himself.

With the completion of the railway from London to Bristol, Brunel became increasingly involved with other projects, leaving Gooch to manage day-to-day operations. He designed his own locomotives and the first, The Firefly of 1840, proved to be extremely reliable. Many more of the class were introduced and the standard of service on the line grew steadily. As locomotive engineer, he drove most of the Royal trains carrying the Queen and became well known to the establishment. The construction of Swindon Works, which became synonymous with the GWR for the rest of its existence, also owed a lot to Gooch.

He was prominent in the great battle of the gauges. Brunel convinced the GWR directors to adopt a broad gauge of seven feet which would allow faster, safer trains. Although largely true, this failed to take into account the many miles of standard gauge track already in use. In 1845 Brunel and Gooch were able to persuade a Parliamentary commission that the broad gauge would be confined to a fixed geographical area and it was thus allowed to continue. Daniel was handsomely rewarded for his part in the victory and by 1851 his salary was £1500 pa.

Brunel’s grand plan for the GWR was to continue to New York using steam ships of his own design. The first vessel, the Great Western of 1838, had proved very successful and when the Great Britain followed in 1844, Gooch supervised the sea trials. Once she was in service, the final ship, the Leviathan, was commenced. Later known as the Great Eastern, it was at the time the largest ship in the world by far. The building, launching and operation of the vessel proved problematic indeed and was thought by many to have hastened Brunel’s demise.

Daniel had married Margaret Tanner from Sunderland in 1838 and by 1841 the couple were living in Paddington Green. A true Victorian family, six children were born between 1839 and 1847. Daniel joined the Freemasons in 1850 and over the next 20 years became very involved with the ‘craft’ as he called it, rising to Pro Grand Master of Berks and Bucks in 1868. His diaries suggest he much enjoyed his Masons’ activities which did him a deal of good in his career.

In 1859 he bought Clewer Park, considering Windsor an ideal place for a country residence. He lived there happily for the next nine years and whilst away on his many travels, he always looked forward to returning to ‘Pretty Clewer’ and his beloved wife. Also in 1859, his friend and colleague, Isambard Brunel died. Gooch observes

‘I have this day (15 September) lost my oldest and best friend’ and by his death the greatest of England’s engineers was lost: a man of great originality of thought and power of execution, bold in his plans but right. The commercial world thought him extravagant, but although he was so, great things are not done by those who sit down and count the cost of every thought and act’.

With Brunel gone, Gooch took a greater interest in the ‘great ship’. He joined the board of directors and sailed to New York on her in June 1860. As the vessel was many times larger than anything else afloat, it attracted huge interest in the US and some £20,000 was raised by allowing visitors to go over her. However, the trip was an expensive one and although it had proved the speed and comfort of the ship, the Great Eastern never fulfilled her intended role as a passenger liner.

The Great Western Railway had become a large and successful organisation by 1860, but politics and vested interests brought about considerable conflict at directors’ meetings. Gooch disapproved of much that was going on and resigned from the board in September 1864 after 27 years with the company. By now well known, he was not short of job opportunities working for time with the Whitworth Company and the Colne Valley Railway. He was elected to parliament as MP for Cricklade, remaining in the House for 20 years.

In July 1865, free from the yoke of the GWR, Gooch set off aboard the Great Eastern on an epic voyage. The ship was to lay the first transatlantic telegraph cable, being about the only vessel afloat which could accommodate the 3000 miles of cable required. It saw the engineer undertaking a task far more challenging than the telegraph from Paddington to Slough installed in 1843. Many problems were experienced. The cable broke repeatedly yet astonishingly, by grappling in 200 fathoms, it was found and spliced several times until unfortunately, on 7 August, the end was lost and the ‘great ship‘ (as Gooch always called it) turned homeward, the task incomplete. There was great disappointment aboard but a determination to eventually succeed in the task.

On arriving home Gooch learned that the GWR was in a parlous finincial state and was approached by the very men who had sought to oust hit to take the chair of the board. He agreed and set about reversing the company’s fortunes at a salary of £5000 a year.

Ie had not forgotten the cable but had a hard time raising the capital for a second voyage because it was the shooting season — everyone seemed to think that shooting down poor birds was a vastly more important thing to do than making efforts to raise capital and attempt to complete the cable.

The finance was found and on 29 June 1866, the great ship set off from Sheerness, better equipped this time to deal with the problems encountered. On 27 July they arrived at Heart’s Content in Newfoundland and brought the cable ashore. This was a tremendous achievement. Gooch’s message to the Foreign Secretary read:

D Gooch, Heart’s Content, 6.30 pm July 27 (1866) to Lord Stanley Foreign Office London: Mr Gooch has the pleasure to inform Lord Stanley that the Newfoundland shore end of the Atlantic cable was laid today and the most perfect telegraphic communication established between England and the continent of America. God grant it may be lasting source of great benefit to our country.”

The following morning the United States president received a message from the Queen — a truly historic event!

Heartened by their success, they returned to the site of the broken-end ol the carlier cable. After three weeks of grappling, it was retrieved and spliced, the ship returning to Heart’s Content with a second functioning cable. Following due celebration and the presentation of an Irish wolfhound to the ship’s captain, they set sail for England. The dog, Norval, was passed on to Daniel and became a faithful friend for the next ten years.

‘I was very pleased, accompanied by my constant companion Norval, to find myself at my pretty home in Clewer on 19 September, grateful to God for His care of me and for His blessing on our work.’

On 21 September he was summoned to the Prime Minister’s office to he offered a baronetcy. In November 1866, the lad from Bedlington became Sir Daniel Gooch Bart, MP.

The next few years were busy ones for as well as railway and cable business, Sir Daniel attended the Commons and sat as a magistrate in Windsor. However in May 1868 tragedy struck when his wife, Margaret, died. It is clear from his diary, much of which was withheld on first publication, that her death had a profound effect. He fell into depression for some long time and often reflected in his writings upon their happy life together and how sorely he missed her.

In 1869 he was back on the Great Eastern laying a cable from France to America. Later that year, whilst in Brighton, he met the second Lady Gooch whom he married in 1870. Unfortunately the fourth volume of his diary is missing so we know little of the circumstances of their meeting.

Meanwhile his business life continued much as before. The GWR was on the road to financial recovery, he strove to keep the Great Eastern in commission with some degree of success as she laid the Indian telegraph in 1870 and a further transatlantic link in 1875. After that, there remained little work for the vessel which ended its days as an amusement palace in Liverpool before being broken up in 1888. Poor old ship, you deserved a better fate he observed ruefully in his diary.

By now Sir Daniel was well into middle age and although he continued to serve on the boards on numerous companies as well as the GWR and the Anglo American Telegraph company, he took to travelling quite extensively with his new wife ‘Bay’, as he called her. After a final cable laying trip to Madeira on the SS Scotia, they decided that foreign travel made too great a demand on the constitution and trips were confined to the British Isles

In November 1885 Parliament was dissolved and to Gooch’s relief he was no longer a Member of Parliament. He expected to miss some aspects of the “club” but was glad to have nothing to do with the Gladstone government and its thoughts of Irish independence. During the year he was also able to travel through the recently completed Severn Tunnel, where his son Charles was an engineer. This was the last major project in which he took an interest.

As he advanced in years, it is clear that Gooch remained alert and performed many duties in relation to his directorships but increasingly he enjoyed spending time at home. In 1889 he became unwell and made an extended visit to Hastings hoping to recover from bronchitis but he returned a sick man and suffered much in his final months. He dies at Clewer on 15 October 1889 and was buried in the churchyard next to his beloved first wife.

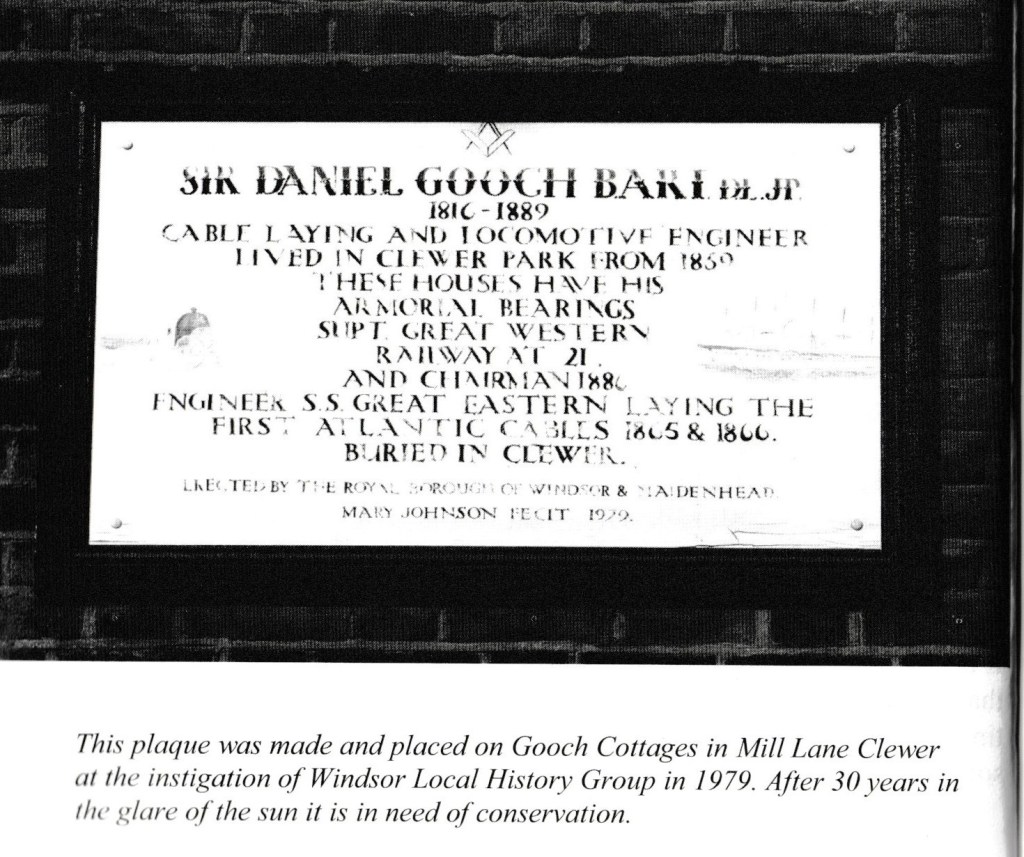

Clewer Park was demolished after the Second World War and but Sir Daniel’s presence is still marked by his grave in St Andrew’s churchyard and a plaque on the almshouses next to the Swan. Until April 1976 another reminder was the 8.02am train direct from Windsor to Paddington. This was originally put on to allow Sir Daniel to travel up to his London office without having to change at Slough. It remained popular with Windsor commuters until rationalisation saw its demise.

Gooch was a gifted engineer and during his lifetime showed himself to be an astute and forward thinking businessman. A great family man who clearly loved both wives and his family, he deserves to be remembered for his contributions to the technology of the day.

Malcolm Lock

Bibliography

Roger Burdett Wilson (Ed), Sir Daniel Gooch Memoirs and Diary, published by David and Charles 1972.

Stephen Brindle, Brunel – the man who built the world, published by Phoenix 2006.