Published in Windlesora 28 (2012)

©2012, WLHG

During 2011 it would have been hard to avoid knowing that the year was the four hundredth anniversary of the King James Bible, due to all the media coverage the event received. In Datchet, we had a particular reason to mark this anniversary because Robert Barker, Printer to King James I, lived at Southlea, just beyond Datchet village towards Old Windsor. The printing business itself remained in London but the Barker family owned a great a deal of property here and Robert made his mark on the village for the future.

Christopher Barker, Robert’s father, had acquired the title ‘Printer to the Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty‘ in 1577, during the reign of Elizabeth I, and on his death, it was inherited by his son. Although the title might sound like a privilege conferred as a favour by a grateful monarch, it was in fact a patent or monopoly which was bought for a considerable sum of money from contentious rivals. The office of Royal Printer was the subject of bitter and expensive legal disputes with other London printers, all vying for the most profitable right, that of printing bibles.

Having made his fortune, Christopher Barker consolidated his status by buying a country estate, as did so many other Tudor businessmen and merchants. In 1583 he bought the estate of Southlea where there was once a grand house, now only represented by Southlea Farm. After his father’s death in 1599 Robert, who never did anything by halves, acquired a great deal more property in and around the village, including the leases of Upton Manor, St George’s Rectory and Eton College’s land in Datchet. His first wife bore him twelve children and his second wife seven more, all but one of whom survived into adulthood.

The greatest responsibility and achievement of Robert Barker’s career was his beautiful printing of the early folio editions of the bible in 1611. This version was the result of King James’ Conference at Hampton Court in 1604 when around fifty scholars were charged with making a new translation from the original languages, more acceptable to both Bishops and Puritans, although the new work owed a great deal to previous English bibles and particularly to William Tyndale’s of 1525. Its printing was financed by what we would call venture capitalism, the investment of a considerable sum of money by Barker and his partners on a highly profitable business project. Robert Barker is said to have set aside £3000 (possibly equivalent to £300,000 today), to pay for newly cast lead typefaces, high-quality linen and rag paper, and all the labour-intensive processes.

But Robert Barker overreached himself. By 1620 he was heavily in debt and his estates were mortgaged to his own partner, partly due to the expenses of the King James Bible but also to the constant litigation he engaged in with rival printers over the rights and profits of the King’s Printing House. In 1631 Robert’s final downfall came with the printing of a bible (known as the Wicked Bible) with a gross error in the Ten Commandments: the word ‘not’ was omitted from the seventh commandment, which thus read, ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’. While all books of the time, including bibles, contained many printing mistakes, this one is more likely to have been deliberate sabotage by an aggrieved rival in order to ruin Barker’s career; it would not have been difficult to bribe a typesetter. Unable to pay the fines imposed by Charles I’s Star Chamber, Robert entered debtors’ prison where he remained until his death in 1645.

Robert Barker’s name would probably have been forgotten in the village but for his association with a charitable trust – the Bridge Trust. Datchet was not originally a village built around picturesque greens, but around a watercourse running through the middle from west to east and eventually to the Thames; it was culverted in about 1850 and the dry land of the greens took its place. There was a bridge over the stream from the top of the High Street to take the road from Datchet ferry over the Thames on towards London, and by the Elizabethan period, this bridge was in need of an endowment for its upkeep. The pub we know as the Royal Stag seems to have been a ‘concealed chantry‘ and in 1570 the Court of Chancery designated its use as a new charity, the Bridge House, with its rent to be used for the repair of the bridge. Local trustees were appointed and the Trust has survived, though the modern trustees make grants to local organisations and projects, largely still from the rent of The Royal Stag. It has come down to us under the name Robert Barker’s Bridge House Trust, although recent research has shown that it was founded long before Barker’s name was attached to it. As the last surviving trustee in the year before his death, he ensured its future by passing the property on to a new set of trustees, and he may have required it to bear his name; certainly, by the mid-eighteenth century, it was considered to have been his foundation. (The community café next door to the Stag is unfortunately called The Bridge, in a metaphorical sense, but it has nothing to do with the Bridge House Trust.)

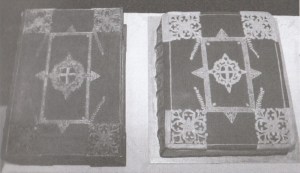

So in 2011 the present trustees were eager to take part in the quarter centenary events and helped to organise all the schools and many societies in Datchet for a most successful day on 7 May. Dancing on the Green was followed by a celebration in church of words, music, and re-enactments of Robert Barker’s life. The centrepiece was St George’s Chapel’s folio King James Bible brought by two archivists, who enjoyed the day as much as the very large congregation – and especially the extraordinary cake made and iced by two village ladies as an almost exact replica of the great bible itself.