Published in Windlesora 29 (2013)

© WLHG

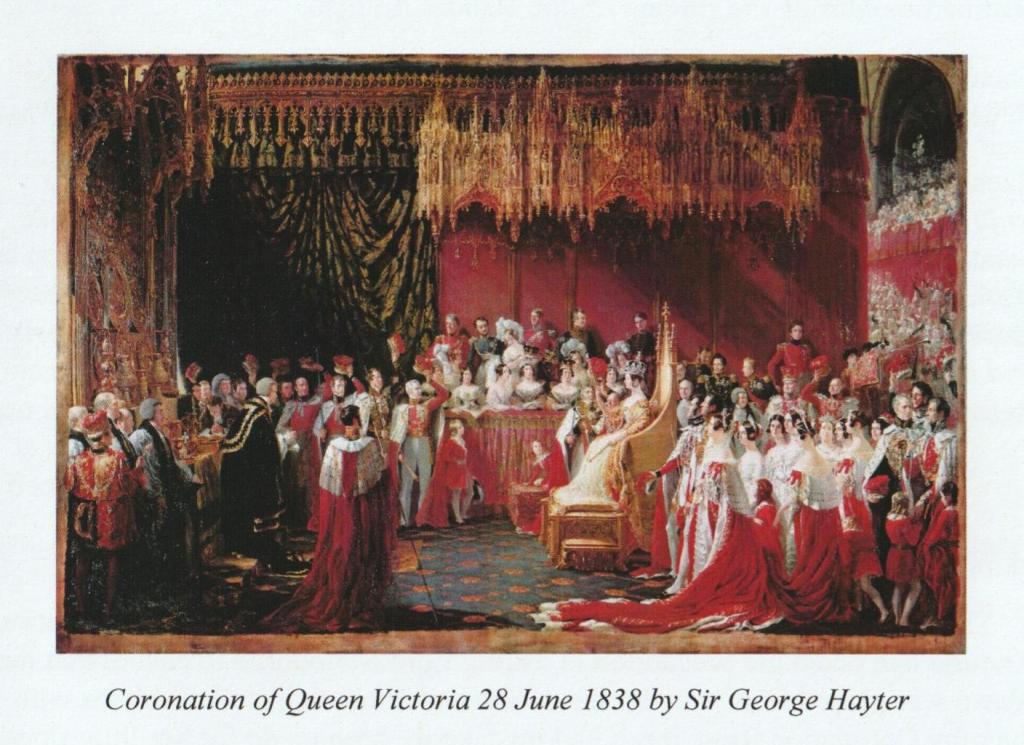

On a fine June morning in 1838, one hundred and fifteen years before the coronation of her great-great-granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth I, Queen Victoria had followed the same route from Buckingham Palace to her crowning. Both Queens were very young: Victoria a mere 19 years and Elizabeth 25 years old and neither had been destined from birth to wear the crown. Victoria owed her title to the death in childbirth, of George IV’s only daughter, Princess Charlotte.

In 1838, as in 1953, London was ablaze with coronation fever as crowds arrived in such vast numbers, that the iron palings round the royal parks were removed to enable the visitors to camp and to sleep there. The ancient ceremony to which both young queens rode had remained essentially the same for one thousand years, but there was a world of difference in the preparation and celebration of the two coronations.

A coronation requires an enormous amount of preparation. Unfortunately in 1838, there was no effective equivalent to Bernard Marmaduke FitzAlan-Howard, 16th Duke of Norfolk, Earl Marshal and Hereditary Marshal of England, to choreograph the ceremony with masterly skill. The elaborate rehearsals of 1953 found no place in Queen Victoria’s coronation. Not until the Queen’s visit to the Abbey on the eve of her coronation did anyone think to suggest that she should try the height of the two thrones both of which were found to be too low.

A coronation is an occasion for pageantry and celebration, but it is also a solemn religious ceremony in which the sovereign dedicates a life of service to the people. No one seems to have troubled to explain to Queen Victoria the nature of the ancient service. Her great-great-granddaughter saw her coronation as a deeply religious commitment and a goodly number of her subjects in 1953 believed, when asked, that she was divinely appointed. To the more skittish Victoria, only just emerging from girlhood, it was a pageant to be got through.

She was surprisingly unfamiliar with the coronation regalia. Describing the format of the ceremony in her journal she writes rather vaguely, “Then followed all the various things and last (of these things) the crown being placed on my head”. Without benefit of any rehearsal or practice in wearing the crown, she found its weight less symbolic than irksome and complained that it hurt her a good deal.

Elizabeth II practised for weeks even appearing wearing the crown at the bath time of her two young children. Victoria was totally unaware of the significance of the Orb enquiring of the Archbishop of Canterbury “What am I to do with it?” and on receiving the answer “Your Majesty is to carry it if you please, in your hand.” She replied “Am I? It is very heavy.” In her journal she records somewhat irreverently the close of the ceremony “The procession being formed, I replace my Crown (which I had taken off for a few minutes), took the Orb in my left hand and the Sceptre in my right and thus loaded proceeded through the Abbey”.

Then again, Victoria’s coronation was marred by undignified behaviour. Her eight train bearers had been provided with mantles which were too long and cumbersome. The result was that they drew the Queen up short as she progressed through the nave. Two of them came in for particular censure. After the ceremony, Lord Melbourne enquired of the Queen whether it was true that two of her train bearers had chattered throughout the service and if so did she hear them. Victoria recorded her answer in her journal; they had and she did! Worse was to follow. During the ceremony the Treasurer of the Queen’s Household scattered silver coronation medals and in the ensuing mélée, generals and peers fought for them on the Abbey floor.

Any unexpected incident provoked stormy applause. During the homage, the unfortunately named Lord Rolle, aged 82 and somewhat infirm, took a tumble as he caught his foot in his robes on the steps of the throne. As he struggled to his feet and prepared once more to ascend, the congregation erupted into raucous cheering. The situation was saved only by the Queen herself. “When he attempted to re-ascend them,” she wrote, “J got up and advanced to the end of the steps in order to prevent another fall”. When the Queen retired to St Edward’s Chapel she was shocked to find the altar covered with sandwiches and bottles of wine. Even the conduct of her beloved prime minister Lord Melbourne came in for censure, for he, as he later confessed to the Queen, was so tired by carrying the enormously heavy sword of state that he helped himself to a glass. One political opponent, and later favourite prime minister of the Queen, observed Melbourne closely. Benjamin Disraeli recorded that the prime minister held the sword of state like a butcher, looking singularly uncouth, with his robes under his feet and his coronet over his nose.

Lord Ward, added the same commentator, was seen after the ceremony with his robes disordered and coronet cockeyed, drinking champagne out of a pewter pot. Then there was the slightly disconcerting behaviour of the Queen’s two royal uncles who could not be restrained from their customary practice of beating time during the singing of the Handel Anthem.

The Queen had a lifelong dislike of bishops. One of her earliest memories was of terrifying bishops wearing strange wigs and aprons, getting down on their hands and knees to play with her and it did not escape her notice that a sizeable list of mistakes were made by the officiating clergy. “Pray tell me what I am to do” she had implored Lord John Thynne, the Sub-Dean, at one point, “for they don’t know’’. The Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Durham came in for special criticism. “The Bishop of Durham stood on the side near me, but he was, as Lord Melbourne told me, remarkably maladroit and never could tell me what was to take place”, she confided to her journal. Before the crowning, he and his colleagues began the Litany too soon, and near the end of the service the Bishop of Bath and Wells turned over two pages at once. He did not notice his error, told the Queen that the service was finished and then had to fetch her back from St Edward’s chapel whither she had retired.

The Archbishop of Canterbury fared no better. Even before the Coronation, Victoria had taken the precaution of asking Lord Melbourne to ensure that the crown was placed firmly on her head. She had not anticipated problems with the ruby Coronation Ring, but it had mistakenly been made for her little finger.

The Archbishop, not withstanding, proceeded to crush the ring onto her fourth finger. “The Archbishop” she complained, “had most awkwardly put the ring on the wrong finger and the consequence was that I had the greatest difficulty to take it off again which I at last did with great pain”.

In a final growl, she complained “The Archbishop tried to give me the Orb after I had already got it and he (as usual) was so confused and puzzled and knew nothing”.

With the natural resilience of youth, Victoria was not the least bit tired at the end of the day, retiring to her mother’s balcony to watch the Coronation fireworks, but not before she had slipped upstairs to give her pet spaniel, Dash, his bath. It would be nice to think that our own dog-loving Queen, might have done the same.