Published in Windlesora 08 (1989)

© WLHG

Maps have a fascination. The older ones are hopelessly inaccurate. But they are often colourful and give us an insight into how men of former ages saw the world in which they lived. This is true of Ptolemy’s Map of the World, originally drawn about AD 150; it is true of the Hereford Mappa Mundi of 1280, recently so much in the news, in which the Red Sea really is red, the Tower of Babel is prominent, there are mermaids in the Mediterranean and Jerusalem is at the centre of the earth. Nearer to our own time the Ordnance Survey maps have developed elaborate legends and keys with their specialised modes of showing woods, orchards, marshes, parks, rough pasture, dunes, quarries, open pits — to say nothing of roads, rivers, estuaries, relief, towns, churches, boundaries, and even wind-pumps and windmills (both disused and in use). All these kindle the imagination and stimulate the desire to explore.

This is all to introduce the Summer Exhibition at the Guildhall. With the title Windsor through the Centuries — Putting Windsor on the Map, it included a representative collection of maps relating to Windsor from 1250 to the present day — some national, some county, some town, some related to a specific topic such as municipal reform, railway projects, schools, the Bier Lane Slum Clearance. Illustrating the maps were reproductions of prints and pictures, together with dioramas from the former Guildhall Exhibition and some solid objects such as a Georgian pedometer.

Maps need interpretation if they are to come to life and the illustrative material helped to do just that. The display was mounted on panels which were both attractive and functional. The titles and explanatory letterpress were easy to read and the setting of the Exhibition in the beauty of the Guildhall Chamber was of course an added attraction. The architect-in-chief of the Exhibition was Judith Hunter, Hon. Curator of the Royal Borough Collection. In the brochure she makes acknowledgement to many sources of help, but the over all assembling and presentation of the material was hers. Once more, Windsor must thank Judith for a fine job of work.

Windsor is a small town by most standards, but it has the Castle and it is the Castle rather than the Town which features in the two medieval maps — Matthew Paris’ 13th century Map of Great Britain and the 14th century so-called Gough Map (now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford) which shows an impressive Windsor Castle close to the Thames. Both maps embody a considerable amount of information, gathered, no doubt, from court officials, county sheriffs, the great abbeys, merchants and travellers of many kinds.

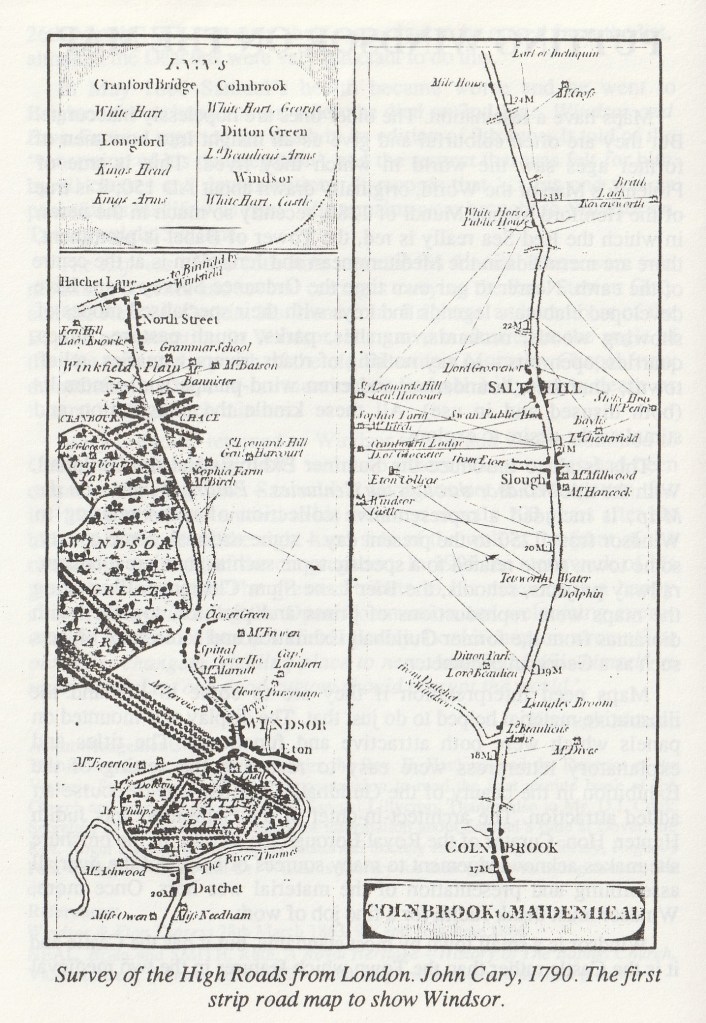

Medieval maps are few and far between. Indeed, after Gough’s map, there is nothing of any note that includes Windsor until Christopher Saxton’s 1574 map of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. This and its companions were the first of a series of county maps, which still left a great deal to be desired but included more and more detail. Not only is Windsor shown, but the Park and the Forest, neighbouring settlements such as Old Windsor, Eaton and ‘Clure’, the River with its bridges, the county boundary (hardly altered until 1974).

The first maps which show Windsor itself in any detail are those of John Norden. Norden produced a series of surveys or views covering the Castle, the Forest and the various Parks for James I in 1607. Three were included in the Exhibition. Even so, they are maps of the Castle,the Little Park and the Forest rather than of the Town. But the town does at least appear, even if somewhat incidental to the Castle. The one most detailed and most often reproduced is that of the Little Park. What an attractive little town Windsor looks, the houses with their bright red roofs clustered beneath the Castle walls, the Market House with its rickety legs, the swift-flowing river with its bridge and its boats! More use could possibly have been made of other views of the Castle which show the neighbouring houses and streets — the engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar made after the Restoration and those by J. Kip in his Britannia Illustrata of 1709. William Collier’s Plan of the Town and Castle of Windsor and Little Park and Town and College of Eton, 1742, marks a big step forward in the cartography of Windsor. It is still primarily a map of the Castle and the Little Park, but the streets and houses of both Windsor and Eton are shown in fair detail. The map shows, amongst other things, how little the road pattern has changed over the centuries.

Judith Hunter says in the brochure: ‘This Exhibition does not do justice to the variety of maps that can be found, but it does give an insight into those that are reasonably available in facsimile or copy form or are amongst the Borough Archives or Royal Borough Collection’. So to say that the Exhibition did not give a complete view of ‘Windsor through the Centuries’ would not be a fair criticism. Perhaps in another Exhibition at some future time it may be possible to give more attention to:

(a) the layout and the history of the Streets behind the Guildhall which formed the nucleus of the original town;

(b) the contribution to Windsor’s history which the River and the Bridges made – up to the opening of the ‘Relief’ Road in 1966 and the closure of the Town Bridge in 1970;

(c) the coming of the railways in the 1840s;

(d) the changes in the pattern of the roads such as the substitution of the ring-road – Windsor to Old Windsor, Old Windsor to Datchet, Datchet to Windsor – for the old London road which continued from the present Park Street by way of Frogmore and the way that passed the south front of the Castle to the ferry (later the Bridge) at Datchet.

There are others too that come to mind. All this is easy to say, but again space and the availability of maps made it impracticable to enlarge the Exhibition. What was shown had necessarily to be selective.

Some of the most interesting of the maps in the Exhibition were those concerned with details such as the houses in the Castle Ditch. Norden’s view shows that some were already there in 1607, but more were built and the plan shown in the Exhibition is dated 1791. A 17th century Windsor lease of one of these houses makes it clear that William Herrendon, apothecary, had ‘to keep the door through the lower room of the premises for a passage into the Castle ditch there for workmen and other persons to pass through for the amending of the Castle Wall’. The property in question is marked M in the 1791 plan, so that the condition still applied. Some sixty years later, in the mid-19th century, the houses were demolished as a part of the process of town improvement.

One slum clearance scheme which received detailed illustration is the Bier Lane (present River Street) area. There were four plans, dating from 1884 to 1927, with the final one showing the proposed Car Park in River Street. It is difficult now to visualise all those scores of terraced houses in their web of mean streets opposite the Castle walls.

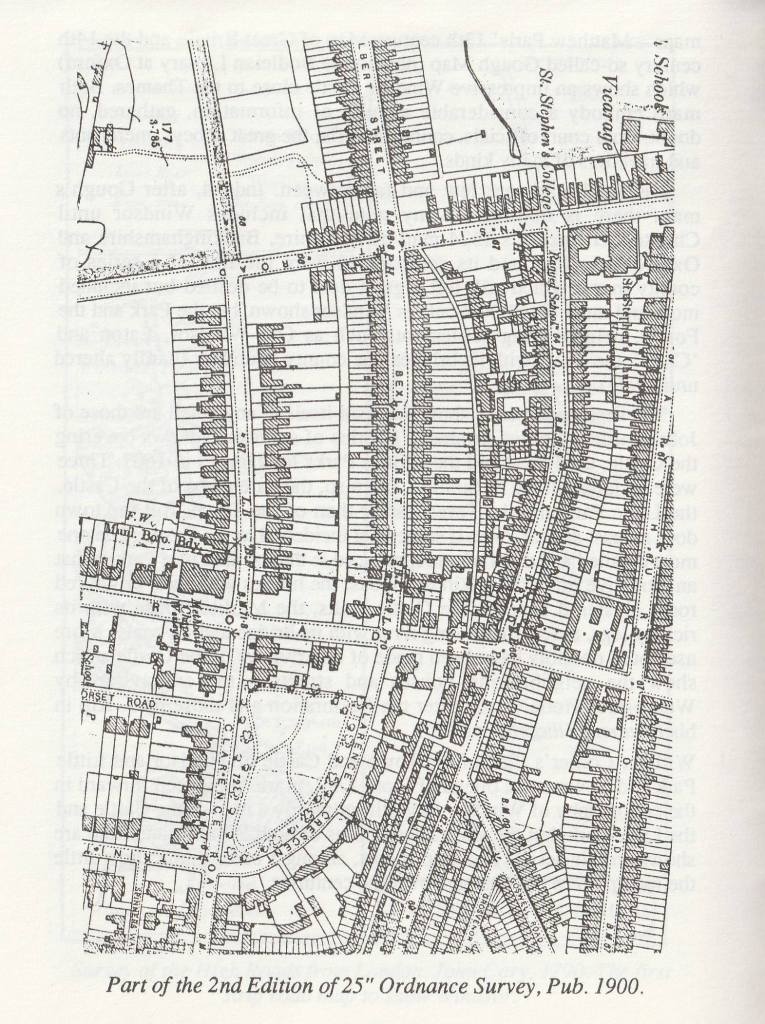

The modern history of cartography is largely the story of the Ordnance Survey. There were on display full and varied examples of the one-inch O.S. maps for Windsor from the first edition of 1822 to the seventh (and last) edition of 1968. Outstanding were the first edition of the 25 inch map of Windsor of 1881 and the first edition of the 5 feet O.S. map which also belongs to 1881. Incidentally there are interesting examples of the time-lag which is perhaps inevitable in map-making. The 1881 maps do not, for example, show the new Wesleyan Chapel in Alma Road which had been opened two years before.

Finally there were draft plans for the future. The past lives in Windsor, but Windsor does not live in the past. Changes have taken place steadily over the centuries. Sometimes the past has been given an new lease of life; Bachelors Acre is perhaps a good example of this. In other instances a completely new 20th century development has taken the place of decaying housing and commercial properties; King Edward VII Court is an example. Windsor has expanded; gone are the vast open spaces to the west shown on some of the Clewer and Dedworth maps. Modern conditions require many adaptations, but all new building development must maintain continuity and not result in fundamental changes in the character of Windsor. So the Exhibition, although an Exhibition of the past, is also a pointer to the future.