Published in Windlesora 22 (2006)

© WLHG

It is generally claimed that Windsor had a larger than average number of public houses than other towns in Berkshire because it is a garrison town. This might be so, but during the 19th century most towns had many more public houses than they have today. Much of the life of the town was carried on there. The poor and working man spent most of his leisure time there, and up to half of his earnings. The homes of the poor were uncomfortable, cold and cramped and often teaming with children. The public house was warmer, more comfortable and much more fun than the home usually was. Public celebrations, meetings, socializing etc., usually took place in the public house.

Until 1823 public houses in Windsor were open all hours and alcohol was cheap. In 1825 (1) Windsor publicans raised the price of beer to 1d a quart; while a 41b loaf of bread could be as much as 10d. By the mid-19th century the price of beer had risen to 4d a quart. Many pubs served food. In 1851 twenty-two of Windsor’s hostelries also called themselves victuallers; they often served 200 people or more during public dinners. Windsor had only a handful of eating houses which were unlicensed. But in many of the rougher public houses, especially in those which were also lodging houses, there were other pleasures on offer besides beer and food, which gained them the notoriety of bawdy houses. In 1839 (2) William Bragg, landlord of the Spread Eagle, William Hazlehurst of the notorious lodging house the Blue Anchor and William Wheeler beerhouse keeper, all in George Street, were prosecuted for keeping bawdy houses ‘of the worst description, dens of infamy harbouring thieves and prostitutes’. They were fined between £20 and £40 each.”

The better class inns and taverns in Windsor served the growing tourist trade, some, like the Bull Inn were respectable coaching inns before the coming of the railway. Public dinners, meetings and gatherings were generally held in the larger inns or taverns. The Swan Inn in Thames Street and the Crown Inn in Peascod Street were popular with the Bachelors of Windsor who regularly held their dinners there, and no doubt much business was negotiated there. The once famous Hope Inn on the Frogmore Road, which used to be the main road from Windsor to Old Windsor, even doubled up as a Catholic chapel. The Abbé Noel Duclos of Evreux, a French émigré of the revolution who taught French at Eton College, regularly said mass in the Hope Inn until 1826, when the first Catholic chapel since the reformation was established in Hermitage Lane. Large numbers of the soldiers stationed in Windsor, many of whom came from Ireland went there on a Sunday morning, convenient for a pint or two after mass.

Coroner’s inquests were held in public houses, not always to the delight of the publican. In July 1836 (3) William Ing aged 66 collapsed and died ‘of apoplexy’ while watering plants in the king’s garden. He was taken to the nearby King’s Arms. The coroner was away in Bath and could not get back for five days. Meanwhile Mr Ing became ‘increasingly offensive’ and the landlady who had to accommodate the body until the coroner arrived, became ‘exceedingly indignant’

Public houses had to apply each year to the magistrate for a licence, which could be refused. In September 1843 (4) the magistrate renewed 40 licences for public houses in Windsor, but Mr Willis landlord of the Free House in Clewer Lane (Oxford Road) had his licence suspended because there had been too many complaints for harbouring loose characters. He did regain his licence on appeal after promising to keep his house in order.(4)

In 1830 the Beerhouse Act was introduced which allowed a householder to retail beer and cider from his own house, on payment of 2 guineas. This was to popularise beer at the expense of sprits, especially gin. The result was that beerhouses sprang up everywhere. It simply is impossible to tell how many beerhouses there really were; many were unlicensed and shut down if found out, only to open up again elsewhere. They were often run by women who sold beer from their front rooms. In 1869 the Act was repealed. The more successful of the beerhouses became respectable public houses; some still flourish today, like the Windsor Castle in Sheet Street or The Trooper in St Leonard’s Road.

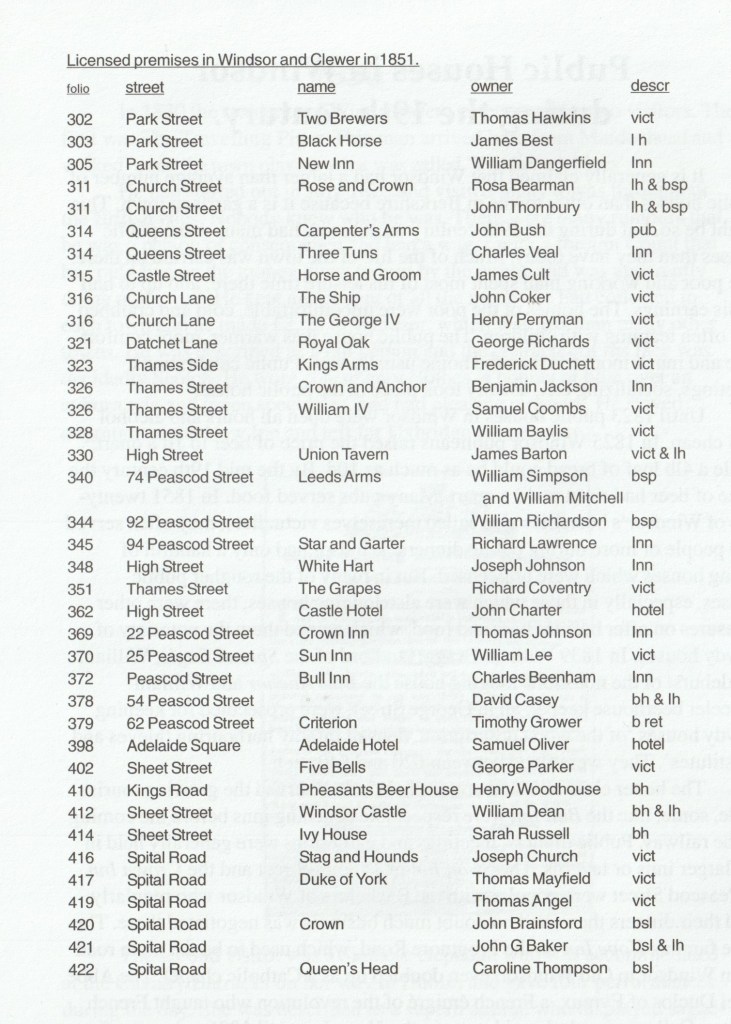

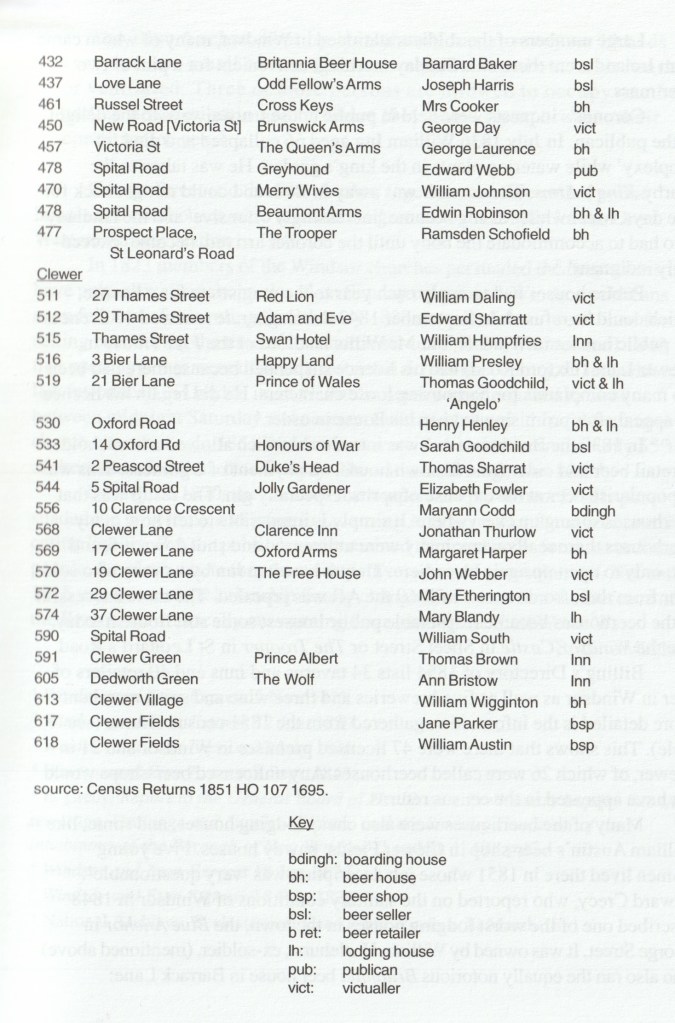

Billing’s Directory of 1854 (9) lists 34 taverns and inns and 40 retailers of beer in Windsor as well as five breweries and three wine and spirit merchants. More detailed is the information gathered from the 1851 census returns (see table). This shows that there were 47 licensed premises in Windsor and 21 in Clewer, of which 26 were called beerhouses. Any unlicensed beer-shops would not have appeared in the census returns.

Many of the beerhouses were also cheap lodging houses, and some, like William Austin’s beer-shop in Clewer Fields, bawdy houses. Five young women lived there in 1851 whose job description was ‘very questionable’. Edward Crecy, (5) who reported on the sanitary conditions of Windsor in 1848 described one of the worst lodging houses in the town, the Blue Anchor in George Street. It was owned by William Hazlehurst, ex-soldier, (mentioned above) who also ran the equally notorious Britannia beer house in Barrack Lane. ‘The Blue Anchor, kept by Hazlehurst, has as many as 70 beds crowded into small rooms which are never cleaned out, whitewashed or ventilated. Three or more persons are allowed to occupy one bed, and no discrimination as to where they come from, or what their condition or sex.’

George Street and the Blue Anchor, together with three other public houses and beerhouses were razed to the ground to make way for the Great Western railway station in 1849.

In 1823 (7) members of the Windsor churches persuaded the magistrates to have pubs as well as shops closed on Sunday mornings. Windsor publicans soon fell foul of this ruling; in February 1823 (7) several of them were fined for selling beer during the time of the church service. But it was not until 1848 that opening hours were officially restricted across the country, in line with a law introduced in London in 1839. Public houses were required to close between midnight Saturday and noon on Sunday, however, this did not improve church attendance. In 1851 Windsorians were shocked to learn that only 55% of them attended church on Sunday. The national average was 56%.8. (8)

During the 1870s members of the temperance movement finally persuaded the government to bring in Licensing Acts to restrict the sale of intoxicating liquors. But the public house remained the focal point for most ordinary people, the place where they found their diversion and entertainment. Not until 1915 was this close relationship finally changed for ever when the Defence of the Realm Act drastically cut opening hours during the First World War.

Brigitte Mitchell

Sources

- Windsor and Eton Express 5 Nov. 1825.

- Windsor and Eton Express 12 Jan. 1839.

- Windsor and Eton Express 23 July 1836.

- Windsor and Eton Express 2 Sept. 1843.

- E. Crecy, Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Inquiry into the sewerage, Drainage and Supply of Water, and the Sanitary Condition of the Inhabitants of the Borough of New Windsor. (London, 1849), p.17.

- Windsor and Eton Express 18 Jan. 1823.

- Windsor and Eton Express 15 Feb. 1823.

- National Archives, Ecclesiastical Census for Windsor 30 March 1851.