Published in Windlesora 10 (1991)

© WLHG

“Name, Jo. Nothing else that he knows on… Don’t know that Jo is short for a longer name. Thinks it long enough for him…Spell it? No. He can’t spell it. No father, no mother, no friends. Never been to school. What’s home?”

In this passage from Bleak House we meet Jo the crossing-sweeper, an orphan whose plight was shared by many in Victorian England. The orphan’s lot was not a happy one, there being little provision for their welfare. The Foundling Hospital had been established in 1739 by Captain Thomas Coram but it was a pioneer. Temporary relief was given by the London City Mission founded in 1835, and Lord Ashley’s Ragged School Union which grew out of it in 1844. These provided schooling, clothing and nourishment, but no permanent shelter. Dr Barnardo did not open his first home until 1870, a year after the Revd T.B.Stephenson, a Wesleyan minister had started the work which became the National Children’s Home. Similar work in the Church of England began in 1881 with the foundation by Edward and Robert Rudolf of the Waifs and Strays Society, now known as the Children’s Society.

There were of course orphanages run by individuals and some were very dubious; readers of Jane Eyre will recall the Lowood Orphanage with its rigid discipline, together with the Brocklehursts, its odious benefactors. Doubtless there were many such as this but it would be wrong to assume that all were like it. Until the larger charities were founded practically the only provision for orphans outside London was the Workhouse. But where orphanages were run by Religious Sisterhoods there was an element of compassion, albeit with strict discipline. The Community of St John Baptist, Clewer undertook the direction of a number of orphanages founded by secular benefactors. The first was St John’s Home Clewer, a home for girls which became the first branch work of these Anglican Sisters.

There were two guiding forces behind the establishment of an orphanage at Clewer — Mrs Rosamira Lancaster and Sister Elizabeth. Mrs Lancaster was the wife of a wealthy City merchant, who with her husband’s support did all she could to help the poor. In 1861 the Lancasters endowed a new Religious Sisterhood in Brompton for convalescent nursing. This became the Community of St Peter, which after several moves established itself at Woking.15

Harriet Monsell, the Mother Superior of Clewer had always wanted to found an orphanage and so she gladly welcomed a request to help Mrs Lancaster who had founded an orphanage in London and was anxious to remove it to the country. The girls arrived at Clewer in March 1855 and were housed in two cottages some way from the House of Mercy. Sister Elizabeth was placed in charge of them and a contemporary record tells us rather quaintly that ‘though she loved children, dear Sister Elizabeth’s heart was at the House of Mercy, and she besought Mother Harriet to let her come back there “if only to do the plates and dishes.”” As Sister Elizabeth came from a wealthy family it is highly unlikely she had ever done the plates and dishes in her life. There were other inconveniences too, notably the long distance from the church. As well as the orphans, a few sick women were also received but it soon became clear that young children and elderly patients did not mix well and so the two works were separated, the work with the sick eventually becoming St Andrew’s Hospital.

The combination of distance from the church and her desire to be at the House of Mercy may well have influenced the generous gift by the newly professed Sister Elizabeth of £3,000 to build an orphanage and complete the House of Mercy chapel. It was a splendid gesture which added a whole new dimension both to the worship and work of the Community. Building work for the orphanage began in June 1857 on land belonging to the House of Mercy a few hundred yards away from the main buildings, and on May 18th 1858 Bishop Wilberforce came for the opening ceremony. Designed by Henry Woodyer in the same style as the House of Mercy and built by Wheeler of Reading in red brick with grey slated roof, the Home was unmistakeably part of the Clewer work and yet remained a distinct and separate entity. Although she was certainly not relegated to washing the plates and dishes, Sister Elizabeth was not put in charge of the new orphanage. The new Sister-in-charge was Sister Harriet, (not to be confused with Mother Harriet) and she took a motherly interest in her charges for many years. Indeed many corresponded with her and visited the Home in later years.

The ‘separateness’ of the orphanage was an important aspect in a class conscious age. To be an ‘orphan’ was to be different, but if the child was illegitimate, there would be an added stigma which would be very difficult to overcome. Thus it was important that St John’s Home, as the orphanage was called, should be sufficiently removed from the House of Mercy so that no one should confuse the older orphans with the inmates there who had been rescued from drunkeness, and prostitution. In 1857 Bishop Wilberforce made the following statement: “The Orphanage is in no way connected with the House of Mercy, except that it is carried on by members of the same Sisterhood… The children are chiefly orphans, the children of respectable parents…Illegitimate children are not admissable.” The Bishop’s words ring harshly, but in fact he was endeavouring to protect them lest anyone should assume that they were the children of prostitutes. Such an allegation would make life more difficult for them in later years.

Mrs Lancaster’s London orphanage had comprised 12 girls, but once removed to the new buildings at Clewer there was room for more. There were two grades: the orphans, consisting of girls over six years, and industrial girls of over fourteen who were trained for domestic service. At first 20 orphans and 16 industrial girls were taken but by 1882 46 could be taken, and by 1888 there was accommodation for 68. The buildings were extended further in 1892-3 by the addition of a new wing connected to the main house by a covered cloister. This provided a sitting room and bedrooms for old girls visiting the Home, and also a new refectory and community room.

Although the official age of admission was six, younger children were taken and boarded out in the parish under the watchful eye of the Sisters. This avoided the otherwise inevitable breaking up of families. Whilst the Home had been built as a result of Sister Elizabeth’s generosity, the fact remained that it had no endowment so that finance was a constant anxiety. By the late 1880’s the cost per child was estimated at £20/4/- p. a. which included food, clothing and share of rent, rates and coals. About £12 per head was paid by friends and relatives, leaving the balance of £8/4/- per head to be raised by the kindness of benefactors or the Sisters themselves. Laundry and needlework brought in a modest income of about £100 which by the turn of the century had increased to about £160.

A schoolroom within the home provided the children with lessons in the 3R’s, history, geography and needlework. It is difficult to say how well educated the children were in comparison with their parish counterparts at the Harcourt Charity School (now known as Clewer Green), or the less fortunate waifs at the Union Workhouse, but at least the schoolroom was under Government Inspection. Education within the home itself shielded the orphans from the cat-calls which so often followed ‘home children,’ but on the other hand it may have made integration into normal society more difficult later. When at the turn of the century the children went to St Stephen’s National Girl’s School they were segregated so strictly that they must have felt more like outcasts than ever before.

The industrial girls were trained in all aspects of domestic service at the end of which they became kitchen maids, laundry maids, and maids-of-all-work. Not all had passed through the orphanage, some had come into the Home at the age of 14 specifically to train as servants. But there was one glaring danger in training naive girls as servants — the House of Mercy Roll Book has many cases of girls from orphanages whose first encounter with the outside world via domestic service led to betrayal and misery.

The earliest account of the daily routine in St John’s Home dates from 1895.

The industrial girls’ day began with a short service in the Home chapel at 6.30.a.m.

followed by a slice of bread and dripping. This fortified them for work in the

kitchen, laundry or house until breakfast at 8.00.a.m. Bible class followed until

9.00.a.m. when work resumed again. Dinner was at mid-day and some free time

until 1.00.p.m. when the kitchen girls resumed work. The dinner break lasted until

1.30. p.m. for the others. Afternoon work lasted until tea time at 4.30. followed by

Evensong at 5.00.p.m. There were lessons from 6.00. — 7.30 on three evenings,

and another evening was devoted to mending clothes.

Life in the Home was not entirely all work and no play, though by today’s standards we might be forgiven for drawing that conclusion. Holidays and outings were not the norm for the working class so we should beware of judging the lack of time off by our own experience. The life of domestic servants, especially the lower strata, was often little short of slavery. At least there was the annual treat when local tradesmen would bring their carts and take the children for a picnic by the river or to Bumham Beeches. The fresh air, and picnic tea were greatly enjoyed, but best of all was the ride. But in 1889 there was a disaster. The Community Annals tell us: ‘The children were all packed into a brake ready to start for Hawley when the horses took fright and dashed through the gateway, knocking against it and were turned into the road, instead of upsetting it into the ditch. They tore down the road until the brake was stopped at the police station.’ It is easy to imagine the panic which ensued and the tears which issued forth from the terrified children all clad in their Sunday best. Let us hope they were compensated by another treat.

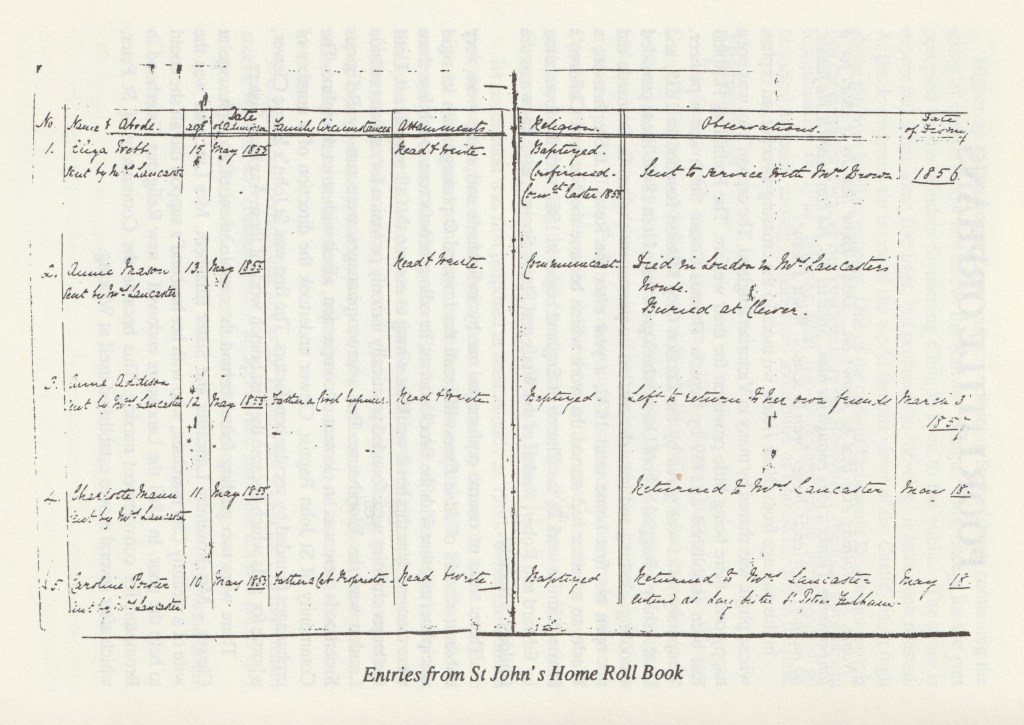

The case books of St John’s Home have recently been rediscovered at Clewer. Most of the children had lost one parent rather than both and many were free cases because there was no one to pay their upkeep. Some had been ill-treated and abused, most were simply destitute. A few were difficult and undisciplined, some had to be sent away, but most did well and made a success of their lives. Space will only permit a few examples.

Emma D. aged 9 years and her baby sister Lucy aged 10 months came from Clewer. Their parents both died in the same week in April 1859 leaving the children destitute. The Revd Henry Hawtrey, vicar of Holy Trinity, Windsor organised a collection for them and lodged the money in a local bank to pay for their upkeep. Both girls did well in life — Emma, the eldest was frail and spent much of her childhood in and out of hospital. In 1864 she went to the House of Charity in Soho and helped there during the cholera outbreak. She later became matron of a Home in Northumberland. In 1877 her younger sister went as housemaid to Mother Harriet, the foundress of the Clewer Community, who by this time was living at Folkestone for health reasons.

A number of orphans found a new life overseas, for instance Emma C. who entered in 1859 aged 12 years. Her father was dead and her mother was in a lunatic asylum. She went to service to a young woman who took her out to South Africa. Another orphan, Mary M. aged 7 years entered in 1860 and in 1872 she became governess to the children of a Russian princess and was last heard of in Florence. Several St John’s girls became governesses to minor Continental royalty and lived abroad.

Many married and settled down happily and sometimes brought their children to see the Home. A few were less fortunate, such as Kate B. aged 11 years who entered in 1861. She was unsatisfactory and left several homes before going to the Old Windsor Workhouse. Mary Jane S. aged 14 years was another difficult case, having left a number of Homes and places in service. But a bad start did not always spell final disaster. Alice L. was a year old when she was brought to Clewer and was boarded out with a family before being transferred to the Home at Rose Street, Soho. In the 1870’s she visited Clewer and the Sisters were glad to hear that she was doing well as a housemaid despite ‘having led a rough life amidst many temptations.’

In 1932 St John’s Home closed as an orphanage, although the Clewer Sisters continued to run several others until the coming of the Welfare State. Woodyer’s building, after subsequent use as a retreat house and a Home for elderly ladies, was sold and it now houses commercial offices. With the passage of time, fewer people will remember the original use of the large red-brick building next door to the Convent and so similar to it in appearance. Although there are many heart-rending stories in the case books there is also a feeling of hopefulness. Perhaps this comes from the fact that the children were looked after with genuine love and compassion, which is why so many kept in touch in later years. ‘St John’s Home is essentially a family, not an institution,” is the way one of the Sisters described it in its heyday. Perhaps that sums it up best of all.

Valeric Bonham

Acknowledgement: The Revd Mother Superior, Community of St John Baptist Clewer for granting access to source material.

Further reading: BONHAM, Valerie. A Joyous Service: the Clewer Sisters and their work.