Researching Windsor Local History

Published in Windlesora 16 (1998)

© WLHG

Research is the life-blood of local history. One of the most remarkable features of RR Tighe and JE Davis’ Annals of Windsor (1858) is the amount of research apparent in its narrative. Footnote references abound, not only to Parliamentary records but to local records such as the Hall Books, the Chamberlains’ Accounts, the Churchwardens’ Accounts—for which they must have gone to the Guildhall and the Parish Church in particular. They went further afield, for example to the Bodleian Library at Oxford, where their use of the Ashmole Manuscripts almost makes it unnecessary for the modern historian to retrace their steps.

A great deal of research has been done over the 140 years since the Annals were published. They provided, however, the base on which more recent research has been built. I will begin by saying something about two sources of outstanding importance.

I was fortunate in that one of my former pupils, Maurice Bond, became Clerk of the Records of the House of Lords and, with his encouragement and guidance, I was able to spend many productive days working on the Windsor records in his charge. At the opposite end of the Houses of Parliament to Big Ben is the tall and stately Victoria Tower. It is here that many of the parliamentary records are preserved. The fire of 1834 which destroyed the old House of Commons was one reason why the House of Lords collection of records assumed such an unrivalled importance. Here there are famous documents such as the Warrant for the Execution of Charles I, along with a host of parliamentary records of every description. The records of the parliamentary enquiries into the many railway bills are here in all their voluminous detail. Those that concern Windsor run into several thousand pages.

Research is not an end in itself. Its purpose is, with the help of the imagination,to re-create history. In my Crown, College and Railways 1 tried to imagine the setting:

The large Committee Room would be filled with MPs lawyers, witnesses, maybe other interested parties, along with attendants, clerks and shorthand writers. The last took down every word and afterwards wrote up the evidence in longhand. The MPs who formed the Committee, apart from an occasional question or comment, for the most part listened to the evidence in silence. The lawyers, on the other hand, questioned and cross-examined as if time was no object, going round repetitively in apparently endless circles, seeking to trap witnesses into contradicting themselves or each other, or making an admission which would be damaging to their cause. (CCR p.44)

Much of this type of research is not only time-consuming but tedious. However,the pains of the tedium have to be endured for the sake of establishing the facts that form the framework of the narrative. Over and above this are the pleasures of serendipity (which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as ‘making happyand unexpected discoveries’). Into such a category comes the comment of Dr Hawtrey, Eton Headmaster about building a railway near his school: “Everybody who knows what Eton Boys are must be aware there are circumstances that occur to induce boys to throw stones when carriages are going rapidly by.” This would“become a favourite trial of skill within a very short time as to how soon a stone would penetrate through two windows at once”. Pressed on this point, the Headmaster expressed his belief, “I think the love of breaking windows is innate in all boys”. (CCR pp. 48-9, HLRO Select Committee: Minutes of Evidence,Windsor, Staines and SW Railway Bill, 15 May 1846).

It was when I was doing research at the House of Lords Record Office that I discovered that strangers endeavouring to enter the precincts of the Houses of Parliament with a brief-case are objects of suspicion, but a pocket notebook arouses no security problem, and I accumulated a pile of notebooks over the years which are now housed in the Borough Collection and are available as research material in their own right. The Victoria Tower at Westminster might seem an unlikely place to find the Windsor railway records. Windsor Castle is a more obvious place to look for the Crown records. Who, however, would imagine that most are housed in the Round Tower? It is not easy to obtain permission to do research here, but it is apleasure and privilege to enjoy if the opportunity comes. We have been lucky not only in having good friends in a succession of Royal Librarians, especially Sir Owen Morshead and Sir Robin Mackworth-Young, but in having two of the Registrars of the Archives—Jane Langton and Elizabeth Cuthbert—as members of our Local History Group.

Many times I have toiled up the long flights of steps that ascend from the doorway near the Norman Gateway, to find the records on which I had arranged to work for that day laid out ready for immediate use. Here I read many of the letters that throw floods of light on the coming of the railways to Windsor, as well as, a few years later, the diaries of Queen Victoria and the future George V, with their frequent references to Virginia Water, the subject of my Royal Lake.

Here every document was filed, indexed, cross-referenced, so that research was a pleasure. At Eton College, by way of contrast, I was presented with the College railway records in five cardboard boxes, and I had to go through these and sort them out before I could even start the research I sought permission to do. I should hasten to add that all this has been put right since. It was, however, a source of modest pride to me when the Provost, Lord Charteris, wrote in his Foreword to Crown, College and Railways: “Mr South has earned the gratitude of the College archivist and of future students during his work on the records at Eton; his special knowledge enabled him to make a detailed list of the documents dealing with the railways”. (CCR p.9)

One of the most fascinating areas of research is pictorial research. A well-illustrated book always gives pleasure. Indeed most people look at the pictures before they look at the text. Following up my leading question, Who would have imagined?, in reference to the Victoria Tower or Windsor Castle’s Round Tower, I can add, who would have imagined that the most extensive pictorial record of Windsor history outside Windsor is at Anglesey Abbey near Cambridge? A former owner had been an officer in the Household Cavalry at Windsor, and while he was stationed there began his collection which is now in the hands of the National Trust.

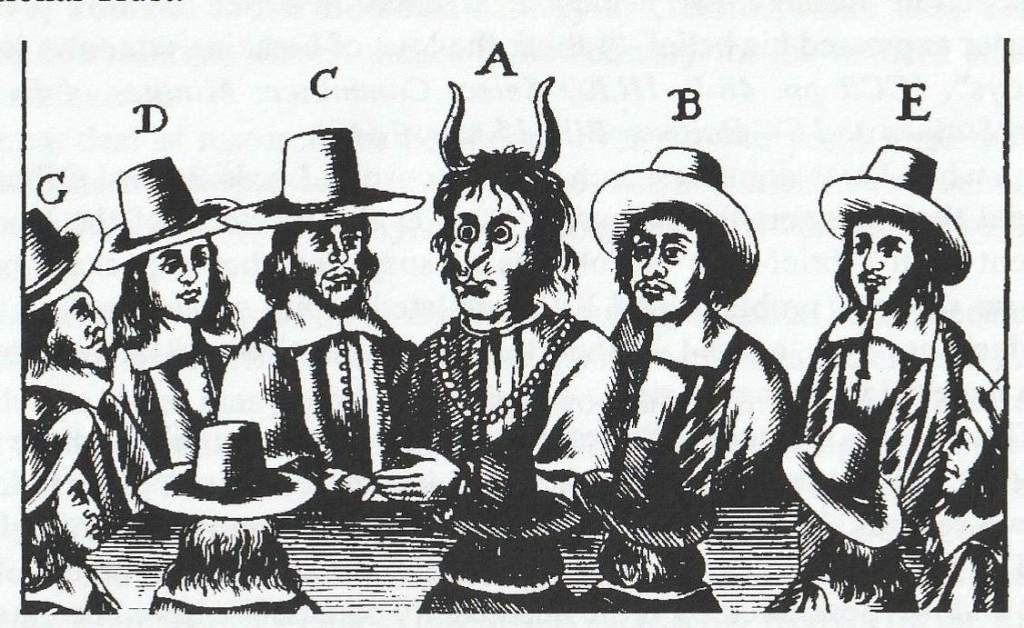

Of the many pictures which I needed for my books the one which gave me both pain and pleasure was the caricature of Oliver Cromwell’s Cabinet Council, which included the only known likeness of Cornelius Holland (G), Windsor’s republican MP. It appeared both on the jacket and as the frontispiece of Royal Castle, Rebel Town. Its discovery, however, took me six months of unrewarding research before it was eventually tracked down in the Archives Department in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery at Edinburgh. Other pictures such as the one that formed the cover picture of Royal Lake—the two young anglers at Virginia Water against the background of Five Arch Bridge and autumn foliage—gave me great pleasure, but none so exciting as the serendipity of the Edinburgh discovery.

Space forbids me to write a comprehensive survey of the many Record Offices and other repositories where Windsor records may be found. When I look back I can, however, select a few that gave me particular pleasure. I spent, for example, many happy and productive hours with the files of the Windsor and Eton Express at the old office at 4 High Street. One of the pains of research which, fortunately, I missed, was the need to use microfilms. The reasons for putting records on microfilm are obvious. It is of course much more satisfying for the researcher to handle the original documents and, when I used the files of the Express in the seventies, it was still possible to do this.

Of all the Record Offices the one that gave me the greatest pleasure to work in was the Library of the London Guildhall. The approach by way of the little underground railway under the Thames from Waterloo to the City was one with which I became familiar. Here there is above all else a wonderful collection of seventeenth century records—Calendars of State Papers, Journals of both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, Rushworth’s Historical Collections 1618-1649, Whitelocke’s Memorials of the English Affairs. The service was courteous, efficient and speedy.

My finest moment of serendipity here was the discovery that the representation of the burning of the Windsor martyrs, Robert Testwood, Henry Filmer and Anthony Pierson in 1544, whose memory was so precious to the Windsor Puritans of the following century, forms the double-page centrepiece of one of the volumes of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs.

There is of course a special appeal in working in historic record offices like the British Library. It is not the easiest record office to use. Techniques have to be learnt, even to track down the reference numbers of the pamphlets and manuscripts (or, as is more likely, these days, the microfilms) to which one needs access. The Round Reading Room of the British Library, however, has a special atmosphere, of which no historian can be unaware (though sadly it is soon to cease to be used in the same way when the Library moves to St Pancras). I used the British Library for the Thomason Tracts, some of which refer to events in Windsor. George Thomason was a bookseller plying his trade in St Paul’s Churchyard. With the greater freedom of the press that flourished during the period of the Civil War and Commonwealth there was an immense output of pamphlets and books. Most of these were collected and preserved by George Thomason and the Thomason Tracts form therefore a unique source for the period. Among them are pamphlets such as Terrible and Bloody News from Windsor, which describes the incidents which marked Charles I’s return to Windsor in December 1648.

Here I must draw my narrative to a close. I am conscious, however, how many record offices where I have worked are not mentioned—such as the Public Record Offices in London and Kew, and the Berkshire Record Office at Reading (the present Borough Collection at Windsor, on which our own member, Dr Judith Hunter, has lavished such care and attention, came after my time). The Windsor historian of the future will be grateful that such a wealth of record material lies ready for use.

Raymond South

(Web editor note July 2023: Books by Raymond South can be found on Amazon, including ‘Crown, College and Railways’, ‘Royal Lake: The Story of Virginia Water’ and ‘Royal Castle, Rebel Town’ all mentioned in this article, as well as his renowned ‘Book of Windsor‘)