Published in Windlesora 25 (2009)

© WLHG

A year before Jane Vigor died in New Windsor in 1783, at the great age of 84, she gave detailed instructions for her funeral: ‘I desire I may be buried in a leaden coffin in the vault where my late dear husband lies in the church yard of Taplow, in as private a manner as possible, no pall bearers, only two horses to the hearse unless the coffin should be too heavy, another four only, with Smith and the Child to attend it.’ Her will, signed in her clear, elegant hand, sums up something of the character of Jane, her attachment to her husband, her dislike of show and ostentation, and her thoughtfulness — even the horses must be spared.

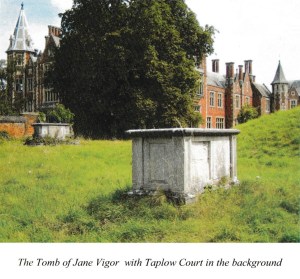

Today the vault in which she lies can still be seen in the old churchyard at Taplow, where the medieval church of St Nicolas once stood, behind the Saxon mound and overlooked by the elaborate towers of Taplow Court. Her inscription can just be read, although her husband’s has been obliterated, simply describing her as ‘relict of the late William Vigor’, which gives no clue to the extraordinary life she led.

Little is known of Jane Vigor’s long life, encompassing almost all the 18th century, first as the daughter of a wealthy clergyman and latterly as the wife of a Quaker merchant, except for twelve tumultuous years in between into which she packed a lifetime of incident. Between 1728 and 1740, Jane travelled to Russia with the first of her three husbands, became acquainted with all the important figures at Empress Anne’s court, was married and widowed twice, and lost at least two children.

When she returned to England, Jane was content to live quietly in Taplow and Windsor, busying herself with charitable works, and it was not until she was 76 that she became known to a wider audience, when the letters she had written during those twelve years were published anonymously as Letters from a Lady who Resided some Years in Russia, to her Friend in England. Nearly 300 years later, these letters, and the eleven additional ones published atten her death in 1785, provide perceptive and entertaining accounts of life in Empress Anne’s Russia.

Despite the secrecy, it was generally known that Jane was the author and the book was greeted warmly. The artist Mrs Delany, a near neighbour of Jane’s during her frequent visits to Bulstrode Park, near Gerrards Cross, admired the book and wrote to her niece Mrs Port: ‘Did I send you the Russian letters? They are natural and informing.’ Within a year the letters were translated into German, French and Dutch and a second edition was published in England in 1777.

What marks out Letters from a Lady are the skill and charm of the writer. Gently humorous, deprecating, but with a shrewd eye, Jane had great powers of observation and a gift for summing up character. Her descriptions of the Empress, her family and courtiers give us an unrivalled picture of the Russian court She inspired love and admiration in all she met, even Empress Anne who, in a letter to George II, commended her. ‘We likewise having a particular benevolence to wards the said Widow for her good deserts, and consequently taking a share in her Well-fare, are desirous on Our side any way, to promote it.’

There in little overt personal detail in the letters for Jane 1s discreet and uncomplaining, although clues can be picked up. We get a clearer picture from those who met her. Elizabeth Justice, a governess in Russia from 1834-7 who wote her own account of her travels, was much impressed by Jane: ‘She has so large a share of sense, that it is only to be equalled, not excelled: And this is known to those who have the Pleasure to converse with her; but seems to be a stranger to it herself. Civility, Affability, and good Nature, are her daily Practices; and, in all her Answers, even to her Inferiors, she shews the greatest condescension, and most obliging Temper. She is, in Person, a fine Woman; very tall, and perfectly genteel.’

Others who met her praise her cheerfulness, equable temper, and quick wits, qualities which stood her in good stead when, in 1728, she was whisked from her quiet home to the deep snows and treacherous politics of Russia. She was born in 1699 and has been described as ‘probably the daughter of the Revd. Edward Goodwin of Rawmarsh Hall, Yorkshire’. However this does not accord with a remarkable anecdote, dated 1740, preserved by the redoubtable Mrs. Delany. It seems to have been told by Jane herself, though recorded by someone else, recounting a strange meeting during her journey back to England in January 1740. She was 40 at that time, had been recently widowed from her second husband and was expecting a child.

Accompanied by an unnamed man, who was in fact the Russia merchant William Vigor, her future husband, Jane was travelling by sledge and had arrived exhausted at Memel, in Polish Prussia. The inn was full of soldiers so Vigor made enquiries about a private lodging and a kindly stranger, named Meyer, directed them to a spacious house, which, to their surprise, turned out to be his own home. When Jane thanked him for his benevolence he explained that the previous year his son had been travelling in England when he fell ill with smallpox in a northern town. As he was lying near death in a dirty alehouse, a gentleman heard of his plight, and took him to his own home. Mr Meyer said that his son owed his life to this gentleman’s goodness.

Jane asked his son where this had occurred and he replied that it was in Methley, near Leeds, in Yorkshire, and the gentleman’s name was Goodwin. ‘Sir,‘ said Mrs Vigor, ‘it was my own father!‘

This curious coincidence seems to confirm that Jane’s father was in fact the Reverend George Goodwin, MA, rector of Methley in West Yorkshire, from 1709-1751. Mr Goodwin, born in 1666, is described as ‘a clergyman of large fortune in Yorkshire, which, after her brother’s death, devolved to her [Jane];‘ and there is an intriguing snippet of gossip from Yorkshire diarist John Hobson, who writes on 31 August, 1728, that he dined with ‘Mr Goodwin, minister of Medley [sic], who had lost £40,000 in the South Sea, and married his daughter to a Russia merchant, and had given her £14,000 to her portion.‘ Jane was greatly attached to her father. His portrait hung in the drawing room of her home, Taplow House, and she wrote of her sadness in leaving ‘a fond father, from whose presence I had never been a fortnight in my whole life till I left him to come into a strange country.’

Jane, beautiful and witty with a large fortune, was a good catch but she was 29 before she married Thomas Ward, one of four sons of the former chief baron of the exchequer, Sir Edward Ward. One of his five sisters was the intimate friend to whom she wrote her letters. In 1728, Ward had been appointed new consul-general to Russia and the couple sailed for Russia, arriving in St Petersburg in July 1728 after one month’s travelling only to find the young Tsar Peter Il had removed his court to Moscow. To make matters worse, Ward’s commission was not acceptable to the Russians because he had no letter of introduction from King George II and it was a year before he was officially recognised.

His wife’s state of mind on starting this strange, new life can be imagined although she was determined to put on a brave face. She wrote to her sister-in-law: ‘Oh, I hear your brother’s step; I must hide my emotion; for If I cannot assist him, which, I know, I should, were he to suspect that I was not perfectly pleased with my present situation.’

Ward had a formidable task for he was also the first person to be appointed to the demanding post of agent for the Russia Company, which until 1698 had had a monopoly on trade between England and Russia. The Wards moved between St Petersburg and Moscow, following the court, and saw at first hand the great changes that overtook the country. Jane describes the death of 15-year-old Tsar Peter II of smallpox on his wedding day on 30 January 1930, and the accession of Anna Ivanovna, daughter of Peter the Great’s imbecile brother Ivan V, after a coup d’état. Of the Empress she writes: ‘She has an awlulness in her countenance that strikes you at the first sight, but when she speaks, she has a smile about her mouth that is inexplicably sweet. She talks a good deal to everybody, and has such an affability in her address, that you seem talking to an equal; and yet she does not for one moment, drop the dignity of a sovereign.’

Painting by Heinrich Buchholtz

Jane gossips wittily about christenings, weddings, funerals, and the lives of the people she met, but has a way of slipping in a sharp-eyed judgement. Describing the protracted marriage celebrations of the Empress’s niece she adds: ‘And thus ended this grand wedding, from which I am not yet rested, and what is worse, all this rout has been made to tie two people together who, I believe, heartily hate one another.’

Jane is more circumspect about her own private life. We learn only obliquely of Ward’s sudden death in February 1731 and her subsequent speedy courtship by and marriage to her husband’s secretary, Claudius Rondeau, on 23 November. Rondeau, born on 28 March 1695, was the son of a French Protestant refrugee who settled in Canterbury. He lived with the Wards and had been a constant support to them, featuring frequently in Jane’s letters.

Jane is coy about the courtship: ‘I am yet wavering and cannot tell what will be the consequence. I think the person has merit, good sense, (as far as am a judge) with great good nature and evenness of temper, if living in the house with him can inform me of his disposition.’

Rondeau is diplomatic. ‘I thought I could do no better than to marry [Ward’s] widow, who is a person of great worth.‘ He explained that ‘this apparent haste was occasioned because of having to be in St. Petersburg by 19 January’.

The cynical might say that this was a union of convenience but the hasty marriage turned out to be a success. Rondeau proved a resourceful and diplomatic British minister resident and agent to the Russia company. Jane’s affection for her husband is obvious and she was glad to advance his career with her influential friendships. He in turn was proud of her position in court and when Jane had to return to London to consult doctors about her health in June 1737, he writes: ‘As she has been nine years in this country and knows everybody at court, perhaps the queen may be desirous to see her.’

The ill health may have been connected with unsuccessful pregnancies. In 1733 Jane lost a child. Writing three months after she was ‘brought to bed’, she is still very weak and has not yet left her room. ‘Between you and me, as this is the first, I should be horribly frightened if I was to find myself in the same condition again,’ she confides. She is ill again the following year, and in 1735 she was delighted to be excused from the new craze for sledging down a frozen wooden run because her majesty said ‘my present condition made it improper’.

When Rondeau died on 5 October 1739, Jane was pregnant again and anxious to return home. Because of her condition, it was thought too hazardous for her to travel by sea so Rondeau’s secretary arranged for William Vigor to accompany her by land. Her daughter, Claudia, was born in England on 8 May 1740, but, sadly, died twenty-two days later, and was buried with Claudius at St Dunstan’s Church, Canterbury.

Jane married once again, to William Vigor, her protector on the long journey home, and for a time they lived in London. Born in 1694, Vigor was rather a nominal Quaker according to his contemporary, the theologian William Law, who describes him as ‘an occasional traveller on the Continent and an interesting talker’. Many Quakers went into manufacturing or commerce at that time, because they were not allowed to earn academic degrees, and Vigor seems to have been a successful merchant. He continued with his Russian interests after his marriage, investing in ships, and using his influence to get his nephew placed in the Russian court.

In 1749, William’s friend John Byrom wrote to his wife: ‘I passed an evening with Mr Vigor, who has left London and taken or bought a house near Maidenhead.‘ This was Taplow House, in Berry Hill, built in the 1740s after the original manor was burned down in 1660. It was a substantial property with stables, garden, orchards, and several acres of arable land and meadow. Many well-known Quakers had settled in that area of

Buckinghamshire, near Jordans, one of the oldest established Quaker Meeting Houses, where William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania, and other early Quakers are buried. Vigor was a great friend of the Penns and is named as an executor in the will of Penn’s grandson, Richard.

The Vigors lived in Taplow for the rest of their married life and, after William died in 1767, Jane stayed on until 1774 when she let the house to William Mowbray and moved to Windsor. There are a few tantalizing glimpses of her lite durimg this time. She subscribed to a book, The Principles of Beauty Relative to the Human Head (1778), by the innovative artist Alexander Cozens a drawing master at Eton College from 1763. Fifty years earlier in St Petersburg, Jane had enjoyed tea and a gossip with Alexander’s father, Richard, who was Peter the Great’s British ship builder.

She was indefatigable in her charitable works and a tribute in The Gentleman’s Magazine says: ‘Her loss will be severely felt by the neighbouring poor, amongst whom she was constantly searching after proper objects for the exertion ol her charity and benevolence.‘ Her generosity continued after her death on 6 September 1783, for she left her money to her servant Anne Smith and for the education and care of Eleanor Allen, the younger daughter of a labourer. Taplow House was inherited by Vigor’s three nieces, and in 1794 was sold to Pascoe Grenfell, MP for Great Marlow and Penryn. Today much changed and extended, it is the Taplow House Hotel. Jane’s charm and wit remained undiminished by age. When her friend, Jacob Bryant of Cippenham, told Mrs Delany about Jane’s death, he particularly mentioned that all her faculties had remained unimpaired. The anonymous contributor to The Gentleman’s Magazine also commented: ‘She retained an uncommon quickness of apprehension and vigour of understanding to the time of her death. Having lived much in the world, and being well acquainted with books, her conversation was the delight of all who had the pleasure of knowing her.’

For those who can track down a copy of her letters, it is still a pleasure to know Jane Vigor and to delight in her account of those twelve remarkable years in Russia.

Alison Haymonds

Additional Materials

Please note that there is an extended version of this article available “Jane Vigor – An Extended Article“. Alison has given us permission to make it available.

Main Sources

Letters from a Lady who resided some years in Russia to her friend in England with historical notes, printed for J Dodsley, London, 1775, republished by Elibron Classics, 2005 (available from online booksellers)

Eleven additional Letters from Russia in the reign of Peter II. By the late Mrs Vigor (with Letters from a lady, second edition), London: J Dodsley (hard to obtain).

The Autobiography and Correspondence of Mary Granville, Mrs Delany, edited by the Right Honourable Lady Llanover, London: 1862.

Anthony Cross, By the Banks of the Neva: chapters from the lives and career of the British in eighteenth century Russia, Cambridge University Press 1997 Leo Loewenson, ‘Lady Rondeau’s letters from Russia’, Slavonic and East European Review, 35 (1956-7).

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online

Yorkshire Diaries and Autobiographies in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, Elibron Classics.

Private Journal and Literary Remains of John Byrom, edited by Richard Parkinson, The Chetham Society 1857.

William Law, William Law and Eighteenth-Century Quakerism, Ayer Publishing, 1994.

Mrs Vigor’s last will and testament, Prob 11/1108, signed and sealed on May 21, 1782.

The Centre for Buckinghamshire Studies.