Published in Windlesora 19 (2002)

© WLHG

Only two monarchs before George III reigned long enough to qualify for a Golden Jubilee, Henry III (1216-72) and Edward III (1327-77), but in neither case was there a great public celebration of the event.

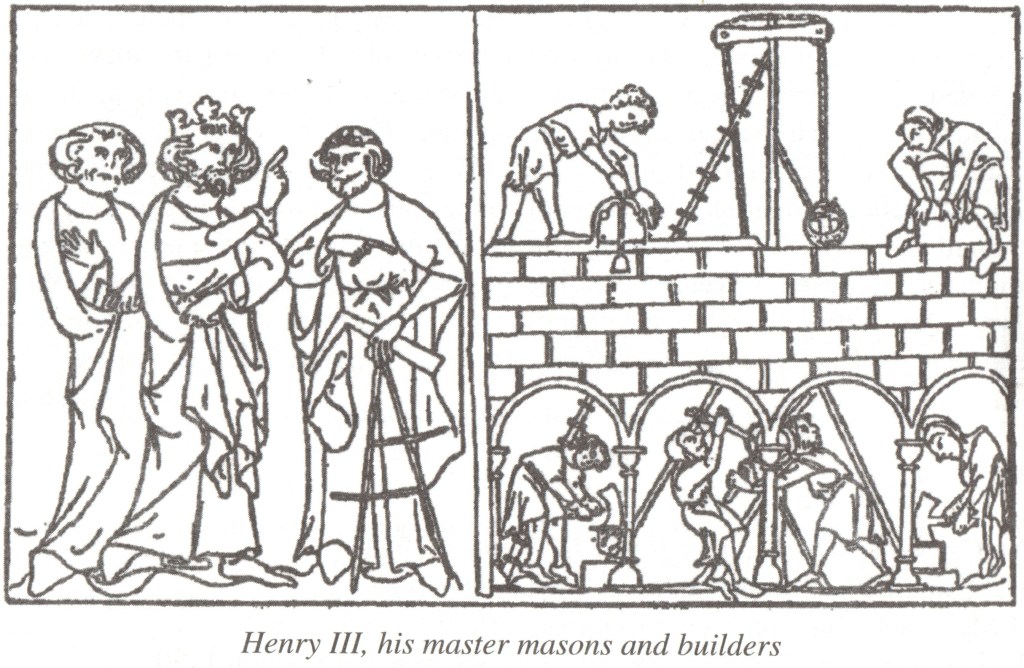

Henry III, the only English monarch to be crowned twice, became king on 28th October 1216 at the age of nine and was crowned in a simple ceremony partly because the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton, was absent in Rome; four years later, at Whitsuntide 1220, he was crowned with due ceremony and splendour, and laid the foundation stone of a new Lady Chapel at Westminster. This was the beginning of Henry’s close association with Edward the Confessor’s church, and of his ambition to rebuild Westminster Abbey. He spent lavishly on buildings throughout his reign: it was Henry who developed elaborate gardens at Windsor Castle and he had glass windows put into Queen Eleanor’s chamber so that she could admire his new herb garden and the garden walks to the ‘fair shrubbery’, the fountain and the vineyard.

When the fiftieth anniversary of his accession was reached in 1266, Henry had just managed to survive a period of major conflict with rebel barons, led until his defeat and death at Evesham in August 1265 by Simon de Montfort: civil unrest continued after Henry confiscated the lands of all de Montfort’s supporters. In June 1266 Henry III and his son besieged Kenilworth which for the disaffected nobles, but the king was eventually, on 31st October 1266, brought to accept the Dictum of Kenilworth, a kind of second Magna Carta which restates the principles of relations between the king and his subjects. And so a Victorian historian, writing in the 1880s and thinking of Victoria’s recent jubilee, describesHenry III’s as a ‘reign which witnessed a jubilee so unlike that of our own time’. However, there was a celebration towards its close when the completion of Henry’s great work, the magnificently transformed Westminster Abbey, was crowned by a ceremony on St Edward’s feast day in 1269, when the bones of the Confessor were translated to the new shrine.

Edward III, who was born in Windsor Castle, also became king as a boy when, in January 1327 at the age of 14, he was more or less thrust upon the throne to replace his deposed father, Edward II. Once he reached maturity Edward’s reign was distinguished by success in war against the French and such celebrations of the values of chivalry as the foundation of the Order of the Garter, but his later years mark a decline: the heir to the throne, the Black Prince, died in 1376 and Edward himself was ill from September onwards. However, in February 1377 parliament was given better news of his health and the Speaker, Sir Thomas Hungerford, prayed that, this being the Jubilee year, the King would be graciously pleased to mark his fifty years on the throne by granting a general amnesty for minor offences and also a pardon to certain persons ‘unjustly condemned’ in the former parliament; these included Alice Perrers, the King’s mistress, who returned immediately to the King’s bedside from which she had earlier been banished. The King remained well enough to summon a council in April and to travel to Windsor afterwards for the St George’s Day celebrations, when a large number of young noblemen were knighted and Prince Richard and his cousin Henry Bolingbroke, the main actors in the power struggle which was to develop twenty years later, were both admitted to the Order of the Garter. Any further thoughts of celebration of the year were abruptly curtailed by a relapse in the King’s health: he died of a stroke at the palace at Sheen in June 1377.

Tony Davenport

Bibliography

DA Carpenter, The Reign of Henry III, London 1996

WH Hutton, The Misrule of Henry IIT, London 1887

M McKisack, The Fourteenth Century, 1307-99, London 1959

WM Ormrod, The Reign of Edward III, Newhaven and London 1990

M Powicke, The Thirteenth Century, 1216-1307, Oxford 1962