Published in Windlesora 29 (2013)

© WLHG

George IV, Prince Regent since February 1811, had no doubt spent much time contemplating his coronation during the nine years before his incapacitated father, George III, finally died in 1820. (For all that time the old man had been imprisoned in his own mind and kept a recluse in a few dark rooms in Windsor Castle.)

The new King loved dress, ceremony and show, and he was ambitious that his coronation should outdo Napoleon’s as Emperor. He was awarded £243,000 by Parliament for its cost, more than £9,000,000 today, and he spent it all and more. His robes alone cost £24,000, and he redesigned the State Crown to make it ‘larger, loftier and more magnificent’, resplendent with diamonds, sapphires, emeralds, rubies and pearls (Windsor Express 15 April 1821). (1) The paper also reported that 20,000 Astrakhan lambs’ feet had been ordered for the black spots on his furred robes and the underside of his 27-foot-long scarlet velvet train (that’s 5,000 lambs sacrificed for his adornment).

Anticipation had begun soon after the accession, the Express noting (28th May 1820) that even before a date had been set for the coronation, houses fronting Westminster Abbey were offered for letting at £2000 or more, while ground in front of the Abbey would be rented out at 8 guineas a square foot.

There was just one problem for the King: his wife. The marriage between the Prince of Wales and Caroline of Brunswick in 1795 had been a disaster from the start, though a daughter, Princess Charlotte, had been born of the union. After the Princess’s death in childbirth, Caroline had taken herself off to Europe, from where reports circulated of her behaving outrageously and installing an Italian lover in her Como villa, but before the King could take action to rid himself of her George III died. Caroline became Queen, at least nominally, a position she was determined to take up; she refused an annuity of £50,000 in return for staying away and instead set off post-haste for England. She was greeted by enthusiastic crowds and continued popular even during her subsequent, much-reported, trial for adultery in the House of Lords: a guilty decision would result in divorce.

By a narrow vote Caroline was judged guilty, but it was clear to the government that the House of Commons would not pass the necessary bill to condemn her (2). However, with all the publicity over her bad behaviour her popularity waned and the King felt emboldened to go ahead. Caroline was informed that queens had no automatic entitlement to a coronation and she would not receive one, but the King felt very nervous about what she and her supporters might do on the day.

Thursday 19 July 1821 proved a brilliant day, hot and sunny. The King dressed up in his finery, which he had based on Tudor costume, with a shoulder-length brown wig and a huge hat with ostrich plumes and a heron feather. Virtually unseen because of the feathers, he also wore on his hat a diamond tiara with a design of roses, thistles and shamrocks: it is known as the George IV State Diadem and is worn when the Queen goes to open Parliament. His train was so long and heavy that eight pages were needed to carry it. Led by a herb-woman and six young women in white (by tradition they strewed flowers and herbs on the ground to ward off the plague), he processed with his pages and various officers of state along a prepared way from Westminster Hall to the Abbey. The King ordered his pages to hold out the huge train so that the crowds could see it properly, though the overweight 59-year-old struggled with his heavy robes in the summer heat.

(RCIN 1051510 34 – Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2013 )

The service in the Abbey was impressive, just as the King had wished, but it lasted five hours and he needed to be revived with sal volatile. Perhaps to his surprise and certainly to his gratification, his crowning was greeted with acclamation. At the end of the ceremony, all repaired to Westminster Hall, where the last ever coronation banquet was held, where first a King’s champion entered on a white charger to challenge any disputants. (the horse had been hired from Astley’s circus and was used to noisy crowds), The King was helped to some turtle soup but soon retired, leaving the rest of the assembled company – unfed since morning, to enjoy the prodigious banquet prepared for them. (3)

The day had been a triumph for the King, unhindered by the Queen: she had tried unsuccessfully to get herself admitted to the Hall, but had had to leave humiliated, and to scoffing from the crowds.

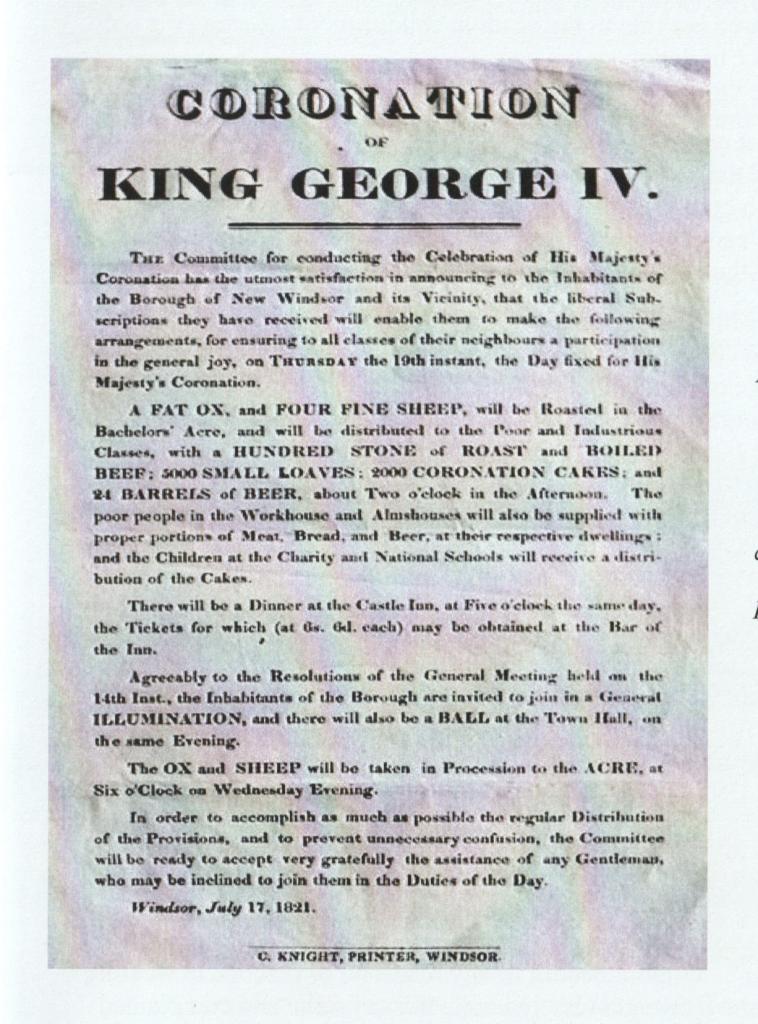

In Windsor there had been determination to ‘celebrate the joyous occasion in a way that should be honourable to the town, and productive of gladness to all classes of the community’ (Express 15 July 1821). It was agreed that the centre of festivities would be an ox-roast in Bachelors’ Acre, with ale, bread and coronation cakes. Money was subscribed to finance the occasion and there were gifts of two sheep, another ox, and firewood for the roasting. On the day before the coronation townsfolk watched as the carcass of the ox was drawn on a wagon by ‘four beautiful horses’ and further carriages bore the second ox and the sheep, accompanied by a party of butchers who ‘made music’ with cleavers and marrow-bones. Grates were erected on the Acre and fires lit.

Coronation day itself was a general holiday. The Castle bells rang out from 5am, and the royal standard flew both from the Round Tower and the tower of the newly-built parish church. In the morning there was a procession of dignitaries and charity children through the town, before cannon were fired at 2 o’clock to signal the start of distribution of the fare to over 4,000 spectators. Inevitably there was a rush to be served and some scrambling, but no real disorder, and the Express reported with pleasure the ‘happy groups of families and friends’. No fewer than 5000 small loaves and 2000 coronation cakes were consumed, and despite the ‘potency of the ale’ there was no obvious drunkenness. The town was illuminated in the evening, and there was a ball at the Guildhall.

The day ended with both townsfolk and their King well-satisfied.

Hester Davenport

Notes

(1) The jewels were hired, and though the King pressed for them to be bought afterwards, parliament refused to pay. The jewels were returned and his crown became an empty shell. The State Crown is the ‘everyday’ crown, worn to open Parliament, which at the coronation the monarch dons after the solemn ceremony with the huge Imperial Crown.

(2) For more details see Windsor and Eton Express 1812-1830:

(3) The Charles Knight Years, Windsor Local History Group, 2012, pp 41-43.

*For a full account see Christopher Hibbert, George JV, Penguin Books, 1976.