Published in Windlesora 17 (1999)

© WLHG

Before the Poor Law Act of 1834, welfare provision in the country had been largely in the hands of individual parishes and towns. The Justices of the Peace and the overseers of the poor superintended a system of indoor and outdoor relief. Everybody had a ‘right of settlkement’ in the parish in which he or she was born, or in which he had resided for a number of years. Anyone who fell on hard times and was unable to work through illness or age, or if a woman was widowed, could apply to the overseer of the poor for relief. This would be provided, where possible, out of charitable funds retained for this purpose and often the result of earlier benefactions. Old Windsor, for example had funds from several legacies.

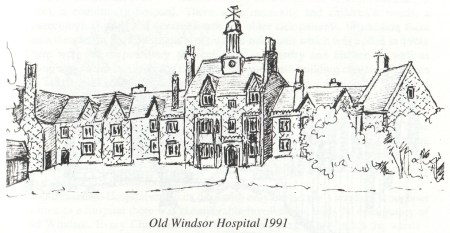

It was because provision was patchy throughout the country that the 1834 act provided for the grouping of parishes to form unions, each of which would be big enough to provide a workhouse for those for whom no other accommodation was available. Windsor and Old Windsor shared a union with Sunningdale and Sunninghill. Old Windsor Union Workhouse was started soon after the passing of the act, and opened in 1841. As it was built on land donated by the crown it enjoyed a pleasant rural setting with sufficient land for orchards and gardens. The building, by Scott and Moffat, was described by Pevsner as of Tudor red brick with diapers, gables and dormers, and a cupola.

Old Windsor workhouse provided for men, women and children of all ages. Separate wards were provided for each age group, but the records show that sometimes when the boys’ ward was overcrowded, older boys were put with the men. However, aged men and women were housed separately from able-bodied ones, and there was a ward reserved for vagrants and tramps.

All those capable of work were obliged to contribute to the life of the workhouse. The men worked under the supervision of the head gardener to provide fruit and vegetables and keep a few animals. The women would have spent their time in cooking, cleaning and laundry work. Inmates who did not perform satisfactorily might be sent to the punishment cells, where they had to break up stones for road mending and pass them through the holes in the wall to prove that the pieces were small enough. These buildings, more recently used as a bicycle shed, are unusual and are a separately listed feature of the establishment.

There were many children of all ages at the workhouse, and their needs were provided for in different ways. At one time a schoolmaster and mistress were appointed by the trustees, but after a time it became the practice for the older children to go to St Peter’s School nearby where the admission books frequently record the child’s address as “The Union’ and their parent as “The Master“. Although some children were at school for several years, it was clearly a transitory population, as for example, when a widowed or unmarried mother married and left the workhouse, taking her children with her.

The Royal Family took an interest in the workhouse. The land on which it was built was given by William IV and the building was opened by Prince Albert. On one occasion in 1863, it is recorded that Queen Victoria made a visit, giving only an hour’s notice, and made a thorough examination of the premises.

It seems that by the standards of the day Old Windsor workhouse took reasonable care of its inmates and local gentry were regular in supplying treats and parties for the children both in the summer and at Christmas time. In the summer of 1863 Miss Thackery of The Grove, gave two parties, one for adults and one for children and in the same year Mr Gouch, a merchant of Slough, gave a party for 48 children and donated a bushel of gooseberries and a penny farthing for each adult.

In December 1879 the master requested the guardians to allow him to purchase the following items for the inmates’ Christmas dinner:

- 180lbs beef (at officer’s price)

- 90|bs fruit

- 12 lbs treacle

- 7/- worth of eggs

- 7/- worth of oranges

- 3/- worth of peel

- 3/- worth of sweets 1lb spice

- 1lb ginger

- 70 lbs best flour

- 30lbs sugar

- 36 gallons porter

- 2 qts mull

- 7lbs tobacco

- 1/2 lb snuff

This was ordered to be provided. The children were also to be allowed tea and a Christmas tree, and aged inhabitants were to have tea.

Sir George and Lady Murray of The Grange also arranged parties for workhouse children and at one of them Lady Murray kindly directed that all the new electric lights in the house should be switched on so that people could marvel at them.

Of course it was not always rosy and the village did not always appreciate the presence of the workhouse. An article in The Lancet described the conditions as well below expected sanitary standards, and whenever it rained the village had to put up with raw sewage from the workhouse flowing down Crimp Hill and ultimately to the river. Villagers did not appreciate some of the people who lived in the workhouse, nor the vagrants who spent odd nights there. In order to prevent them from patronising the Oxford Blue public house in Crimp Hill a new beer house was built nearby, called The Union and holding a sub-licence from the Oxford Blue to sell beer but no spirits.

In the early days the vagrants paid for their night’s lodging by breaking stones, but after the First World War they had to chop firewood instead, and bundles of wood were sold for 1d each in the village. Village people remembered that vagrants would hide their possessions in ditches around Crimp Hill before arriving at the workhouse.

At one time the workhouse had some specially built prison cells in which prisoners awaiting trial at Reading Assizes were held. In 1874 a special tramps ward was built, but it was sometimes difficult to keep inmates in good order. The guardians were at all times keen to remove people to other unions if it could be proved that another parish should be responsible for them, and there are many records of lunatics being removed to an asylum. However, the union does seem to have taken an interest in the future welfare of the children in its care. In the 1870s it became Canada. In April the practice to arrange for orphan children to emigrate to 1874, seven boys aged 11-14 and six girls aged 8-10 were escorted to Ontario by a Miss Rye. Of these, seven were orphans and others had been deserted by their parents. The records show that in 1876 the trustees were still taking an interest in their well being and letters and some photographs were received from them telling how they were getting on in their new homes.

Other children were apprenticed to trades in the district. On 9th March 1875 Mr E Hills, a hairdresser of 93 Peascod Street, applied for an apprentice and selected Walter Palmer aged 13 who had been deserted by his father and whose mother was dead. However, the apprenticeship did not happen as the guardians did not think it a good enough business. William Sobey was apprenticed to Mr Jackman, a baker of Peascod Street. The boy expressed himself satisfied and a cheque for £7 10s Od was authorised. Shortly afterwards, however, the baker went bankrupt, and the cheque was cancelled and the boy re-apprenticed elsewhere.

In December 1902 the Board of Guardians complained of unduly severe treatment of a workhouse boy, William Blankett, by the village schoolmaster and this was investigated. The committee came to the conclusion that “under the circumstances every allowance should be made for the action of the master in cuffing William Blankett with his hand,” as they doubted whether “any schoolmaster when being kicked in the shins by a refractory boy could be expected to refrain from treating him in a similar way.”

The Chapel at the workhouse was refurbished in the 1870s largely by the Misses Rooper who supplied books and embroidered furnishings and linen. The vicar, Mr Harwood, arranged an-opening ceremony in 1880. It seems that Rev. Rooper, who lived at Ousley Lodge, often took services there as he is on record as complaining about “unruly behaviour by the paupers”.

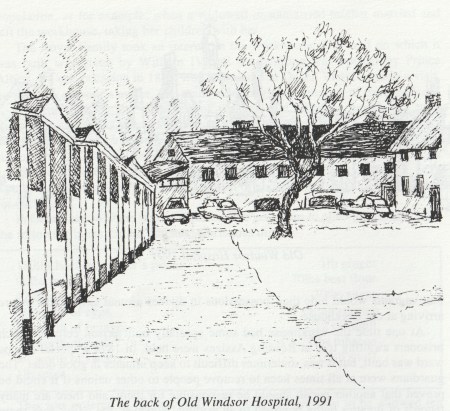

In the 1920s the workhouse was sometimes referred to as the infirmary and this may suggest that parts were used to accommodate casualties of the First World War. In 1940 it was definitely used for convalescing servicemen and eight huts or prefabricated wards were added at the back of the older buildings.

In 1948 when the National Health Service took over, Old Windsor became, in effect, a community hospital. There were maternity and children’s wards, a gynaecological ward and several wards for older sick patients. In addition there was a theatre, an X-ray unit and a premature baby unit which was added in 1960. There were all the ancillary services such as laundry and kitchen as well as dining and social facilities for the staff. The old main building contained offices and old peoples accommodation which was administered separately by the social services department. Some doctors and nurses lived on the premises and others lived at Newton Court Nurses Home. Conversations with people who knew it revealed the hospital (known as King Edward VII Hospital, Old Windsor) to be friendly and well run. Many Windsor and Old Windsor children were born there in the 1960s and villagers were sorry when, in 1970, children’s and maternity wards were closed. At the same time the last of the old people administered by the social services were moved to Windsor.

Old Windsor Hospital ended its days with only old people’s wards. Throughout its time as a hospital there was considerable involvement with the community of Old Windsor. Every Christmas the Church choir sang carols in all the wards -quite a marathon effort in the early days with 10 wards. Local musical and dramatic groups visited and latterly evensong was sung in one of the wards once a month. In the 1960s, the Chapel was well used, being open at all times. When Rev TD Herbert was vicar he was often called up to the hospital to baptise babies who might not survive, and he was always keen to see that the mothers who wished it were churched before they left hospital.

When the hospital was closed in 1991, there was considerable debate as to what should happen to the building, which was in a dilapidated condition. Some favoured just letting it fall down so that the land could be returned to the park, but as it is a listed building, most favoured institutional use. However, it became apparent that the cost of renovation was prohibitive and could only be financed by building houses. After a protracted period of planning enquiries, Berkeley Homes obtained permission to demolish the old 1940s wards and convert the buildings into houses, building some more in a similar style.

Old Windsor residents were amused when it was discovered that the workhouse was being marketed as The Mansion. The agreed name for the development is Bears Rails Views as it overlooks the site of the bear pits of Georgian times, but local signposts still call it Windsor Park View. In its journey of 160 years from workhouse to mansion,the building reflected the social history of the times.

Margaret Gilson

References

Records of the Old Windsor Union, held in Reading

Reynolds, Margot: “King Edward VII Hospital, Old Windsor“