Published in Windlesora 22 (2006)

© WLHG

If asked to suggest how people were entertained in the middle ages (roughly, 1000 — 1485), perhaps many people would be hard pressed to think what entertainment there could have been, outside knightly tournaments, jesters and minstrels — the entertainment of the rich. In fact, this ‘popular’ picture of the middle-ages is pretty accurate. Historic source material has surprisingly scant information on how ordinary people entertained themselves, outside ‘home-made’ entertainments such as story-telling, singing and dancing. On the other hand, the entertainment of the rich was perhaps more diverse than is commonly understood. As Windsor was a royal town from possibly 700, and an important place of pilgrimage (particularly for Londoners) in the fifteenth century, the town is fortunate in having more records of its medieval history than many others.

As with much medieval local history, however, we are restricted in knowing about certain aspects of society by the limitations of surviving source material. Although government records, property charters and wills have survived in considerable quantities for Windsor, these documents only include occasional references to matters of every-day life. In addition, the surviving records tend to refer only to the activities of the relatively small numbers of rich and famous people. But even given these restrictions, it is clear that ‘entertainment’ was more widely defined seven hundred years ago than we might think. The interest in literature is a case in point. Most people imagine that except for monks and a few literate clerks, medieval people were illiterate; some tour guides incorrectly claim that even the kings of England before the sixteenth century were illiterate. In fact, the contrary is true: many people could read in the middle ages including, by the thirteenth-century, some of those in the peasant or villein classes, as their surviving Windsor property deeds demonstrate.

Although today we conflate ‘reading’ and ‘writing’ within the term ‘literacy’, these were considered two separate skills in the middle-ages. Writing was a highly technical occupation involving not only a command of Latin, but the conventions of the shorthand used in writing all medieval documents. In addition, parchment (made from stretched animal skins), quills (typically a crow’s feather), correcting knives (pen-knives) and ink (made from ‘oak apples’) all had to be prepared and used in the correct fashion. This demanded a special expertise that effectively limited the skill of writing a small number of trained clerks and scribes. Reading by contrast was a more widely held skill with some people, and particularly the aristocracy, being considered highly literate. For example both Henry I and Henry II were described as being ‘litteratus’; a designation of their considerable learning. Clearly not all medieval knights spent their time oppressing the peasants or fighting battles in armour, as some may think. King John owned a library in 1203 as well stocked as any monastery, commanding that ‘a romance [ie a poetic text in French] of the history of England’ was sent to him at Windsor; evidence that John enjoyed quite elevated literature. Typically, such texts would have been read aloud in gatherings of the court in either the language of romance (old French) or simultaneously translated into vernacular middle-English. John’s court was resident in Windsor for two sustained periods, in 1204 and 1215 and it could be imagined that such readings would have taken place in one of the royal halls (probably in the area now known as the lower ward) of Windsor Castle. Furthermore, John read Pliny in Latin and was the first European monarch to have shown an interest in modern (twelfth-century) theological texts. Although John is best known for his grudging approval of Magna Carta he followed his father in counting intellectual pursuits amongst his sources of entertainment, as did many others of noble birth. Certainly John was not ‘illiterate’, as was claimed by Tim Marlow on a recent television program about Magna Carta, who cited the lack of John’s signature on the charter as evidence of his lack of education. A little more research would have revealed that personal signatures had no legal significance in the middle-ages (except for Jews); seals were used to authenticate documents. So much for TV historians!

The public reading of heroic tales or morality stories was very popular, and continued to be throughout the middle-ages, as the surviving fifteenth-century tales of Robin Hood testify.

The various strands of the Robin Hood story suggest that parts came from a French verbal story-telling tradition and others from England, such as the ‘green uniform’: where dress as an indicator of station was particular issue of the fifteenth century. The Robin Hood tales grew from telling and re-telling; weaving the traditions of at least two countries into a single story.

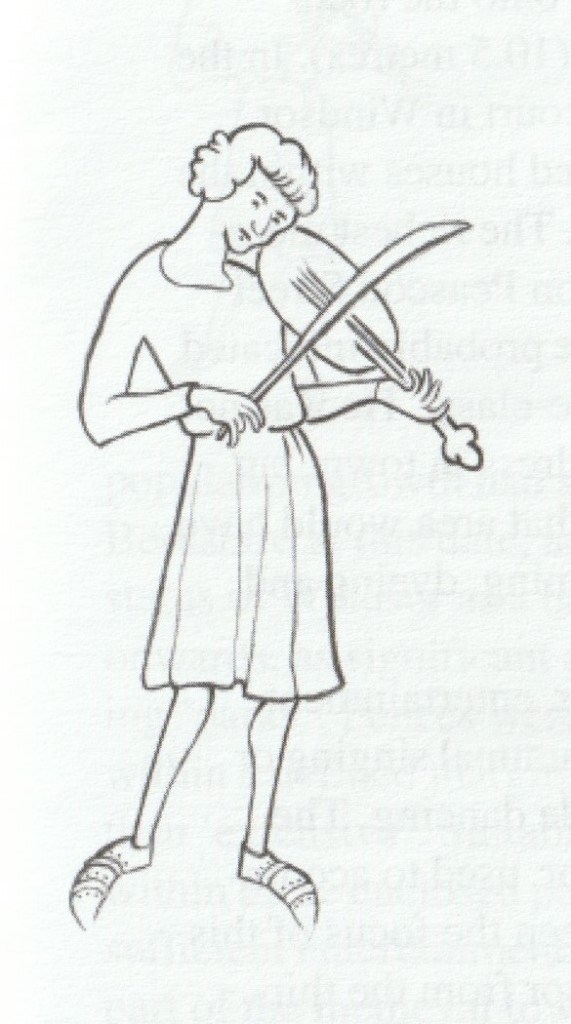

The records held at St George’s Archive, Windsor have details of the people who lived in medieval Windsor, and described themselves as ‘entertainers’. For example, in February 1386 Henry Marshall ‘the king’s minstrel’ (this would have referred to Richard II) purchased two adjacent houses and gardens near Windsor Bridge from William Hugin ‘a mason of Corf Castle’.

The designation of Henry as ‘the king’s minstrel’ seems to imply that he entertained the king as a solo performer rather than as part of a troop, possibly singing and playing a stringed instrument. In contrast, Thomas Haliday another Windsor resident was simply described in 1442, as ‘a minstrel’, in an acquaintance to a £10 bond to John Plummer. Thomas appears to have no royal connection and presumably made his living outside the castle. There is no reference to him owning property in the town. It seems that being a royal minstrel was a well paid profession however, as it allowed Henry to purchase two houses in Windsor from the mason William Hugin, who undoubtedly would have been involved in the extensive rebuilding of the upper ward of the castle, between 1350-68. These houses would probably have been joined into a single substantial, timber framed structure, having a frontage onto the road (following medieval custom) of two poles (10.5 metres). In the middle ages, many of those who attended court in Windsor Castle, either as servants or courtiers, owned houses within the town and Henry was typical in this respect. The richest member of the town community tended to live on Peascod Street and so Henry’s houses near Windsor Bridge, probably indicated that he was part of the town’s small ‘middle-class’. He was not quite rich enough to move into the best address in town, but had to be content with neighbours who in that area would have been engaged in the (noxious) trades of tanning, dyeing and butchery.

For the majority of people in Windsor, entertainment would have been ‘home-made’ such as communal singing or story telling or during good weather, outside dancing. The large number of inns and taverns in Windsor, used to accommodate visitors to the court, would have been the focus of this activity. Tavern keepers are noted in Windsor from the thirteenth century, although the names of their individual taverns, such as the Cross Keys, Saracens Head or the Black Eagle are only noted from the fifteenth century. The early tavern keepers in Windsor, such as William le Barbour (1280), or Osbert le Taverner (also town bailiff, 1330) were clearly wealthy, as the seals they used to purchase property were finely engraved, probably being made by London goldsmiths.

In several respects it would seem that there was a sharp division between the type of entertainment enjoyed by the rich and that enjoyed by the poor. Minstrels were clearly the preserve of those who could afford to employ them. Equally, covered space for dancing was a luxury preserved for wealthy, such as the ‘daunsyng chambre’ included in the Queen’s tower in the refurbished upper ward of the castle in 1368. However, in one aspect the entertainment of the rich and poor had a degree of similarity, that is, in the love of blood sports. For the rich the pursuit of hunting and hawking is well known — one of the primary and enduring attractions of Windsor Castle to aristocracy from the earliest dates, was its proximity to Windsor Forest and the opportunities for hunting. The poor quality of much of the land in east Berkshire preserved it from ‘assart’ (conversion into agricultural land) in the twelfth century, whereas the pressure of a population growth had seen the clearance of woodland in much of west Berkshire at this date, and its consequent loss to aristocratic sport. The status of Windsor as a base for hunting was (re)underlined from 1350 onwards, as significant areas of Windsor Forest were enclosed as hunting ‘parks’. Fences were set over considerable areas to trap quarry within a defined margin, allowing the sport to be more ‘intensive’ rather than ‘extensive’. Suitable animals, such as red deer, would be stocked within these enclosed parks, ensuring that a day’s hunting provided sufficient entertainment. As part of these arrangements, a substantial part of the medieval town of Windsor, known as ‘le Worth’ in Underore, (the modern playing fields of home park) were imparked and cleared of housing in the fifteenth century, to provide a royal deer chase and ‘grandstand’ for spectators — a feature prominently recorded on Norden’s 1607 view of the castle.

The ordinary people’s involvement in blood sport was probably limited to cock fighting or the baiting of wild animals — particularly in this context, bear baiting. There are more references to bear baiting in the extant source material than to any other popular entertainment.

Although many people today consider the medieval period to be dominated by dark periods of war, plague or famine, in fact for ordinary people, there were long episodes of stability. Windsor was known as a place of royal entertainment and no doubt, given the almost continual growth of the town throughout the middle ages, of popular entertainment too.