Published in Windlesora 13 (1994)

© WLHG

Edward Lear came to Windsor in a wet and changeable July 1853, to paint a large picture of the famous view of Windsor Castle from St Leonard’s Hill. He stayed in Clewer Green just below the hill at the Prince Albert Tavern, a pub still found at the junction of Clewer Hill and Winkfield Roads. (Clewer Green was originally a small village built around a green, distinct from the riverside Clewer, but it lost the open space in 1817 and later even its name). While there Lear wrote a funny, grumbling letter about his experiences to his friend and fellow artist, William Holman Hunt.* Lear loved to play with the sounds of words and he tells Hunt that he has “two very good-sized and crumbfortable rooms enough”, but he nevertheless declares that he finds Clewer Green a “perfect prison”.

Lear is best known nowadays as the author of inspired nonsense poetry such as ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’, ‘The Pobble who had no Toes’, ‘The Quangle-Wangle’s Hat’ and so on. But he made his living as a landscape painter. Today his small spontaneous water colours are highly prized, but Lear hoped to make his name with huge oil landscapes like the eight-foot ‘View of Windsor Castle from St Leonard’s Hill’. This picture had been commissioned by the 14th Earl of Derby, a distinguished public figure who became Prime Minister for a brief period in 1851, and who in the 1850s was tenant of the grand house which then crowned St Leonard’s Hill. (Nothing of this mansion now remains, though a few ruins of the building which succeeded it can be found). Lord Derby’s father had first “discovered” Lear and become his patron. The Windsor Castle painting was to be a companion piece to a large picture of the Acropolis which had been commissioned for £100 by the 13th Earl and hung at the main family seat, Knowsley Hall in Liverpool.

Lear was a self-taught artist (even so he was for a time painting tutor to Queen Victoria), but at this period he was taking tuition from William Holman Hunt, co-founder with John Everett Millais of a group of artists calling themselves the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood or PRB. In rebellion against the rigid rules and traditions of the Royal Academy which had been laid down by its founder, Sir Joshua Reynolds (whom they nicknamed “Sir Sloshua”), the Pre-Raphaelites disliked the Academy’s emphasis on copying old masters such as Raphael, and scorned many of the prescribed techniques of painting. These included laying down on the canvas a ground of a tarry substance called asphaltum; instead Hunt initiated the use of a white ground to set off clear bright colours.

Above all the PRB made truth to nature the cornerstone of their creed: landscape or natural backgrounds must not be painted from sketches in the studio, as had been Lear’s practice, but in the open and in front of the subject. Thus Hunt creating ‘The Light of the World’, his portrait of Christ based on the words “Behold! I stand at the door and knock” from the Book of Revelations, set the scene in a moonlit orchard. He felt it essential therefore to paint a real orchard by real moonlight, and so on several freezing November nights in 1851 he sat meticulously painting away in a little shelter he had knocked up in his uncle’s orchard, his feet protected from frost-bite in a sack of straw.

‘The Light of the World’ – which was to become one of the best-known and most-reproduced paintings ever – was still being worked on by Hunt when Lear got to know him, and he asks about its progress in the Clewer letter. But it was this insistence on absolute fidelity to nature that was at the root of his troubles then.

The two men were introduced to each other in the summer of 1852, when it was agreed that in return for tuition in Italian Hunt should tutor Lear in painting. They stayed together at Clive Vale Farm, Hastings, and got on well even though Lear, then forty, was fifteen years Hunt’s senior. The paper on which he writes his letter from Clewer is headed by an engraving of the “Lover’s Seat” at Fairlight near Hastings, and he has marked a cross at the corner: this is a reference that Hunt will understand, for he had chosen the spot for the background of his allegorical painting “Strayed Sheep”, and it was here that Lear sat with him and watched and listened and tried to put the new ideas into practice himself. The simple X conveys a wealth of feeling.

Lear did his best to adopt Pre-Raphaelite techniques, saying that although he’d never make a Brother, he could be a son and a nephew. Hunt therefore became his “Pa” or “Daddy”. But it was one thing to practise Pre-Raphaelitism with Hunt to advise and encourage, another when he was on his own a year later. Like many comic geniuses Lear was given to melancholy, and when things went wrong it quickly turned to despair. Here is his letter, transcribed just as he wrote it. It shows his anxiety, but also the engaging qualities of his idiosyncratic writing:

My Dear Hunt,

I should like soon to know how you are getting on with the nightpiece: if you have done the breastplate & the bat, & if your teeth – (or the places they filled) are better! (1)

Very probably you have been at your Uncle’s at Epsom-Esher-Ewell-Ealing, & so have not been working at all. Send a line to your son, daddy. (2)

What do you hear of the Scottish party? – “studying heath”. I wonder if Millais will write about Miss Stuart-Mackenzie: she is worth writing about. (3)

Have you seen the Haydons naughtybiography, edited by Tom Taylor? I have read it all through, partly in the streets of London, (where I tumbled over an old woman & a barrow of goodseberries,) & partly down here. You will be pleased to find out from the authority of his niece, that Sir Joshua Reynolds used to use a large basin of Asphaltum, & as he walked about the room, it used to drop on the floor. The anecdotes about Wilkie, the Duke of Wellington etc & etc are beyond idea amusing. Tom Taylor has done it all well. (4)

As for my progress here, it is nothing, or worse. I sometimes think I cannot get on – & must give up the picture, – but the homilies I used to pour forth to you last year on the moral ill effect of “giving up” anything undertaken, reproach me horribly. The sky is always beastly blueblack, & I have sent for no end of tubes of the ingredient:- & during this week the sun has shone twice.

The sky is always beastly blueblack, & I have sent for no end of tubes of the ingredient:- & during this week the sun has shone twice.

It is therefore utterly impossible to do this view on a strictly PRB principle, – for supposing a tree is black one minute – the next it’s yellow, & the 3rd green: so that were I to finish any one part the whole effect would be all spots a sort of Leopard Landscape. I must therefore – if ever there is sun again (towards evening,) mark out the shadows grossly & work away as I can. All the distance also is blue, gray & black – dark and light – by fits, – & the castle which should be in strong light and sharp has been for 2 days jet black – 2 more scumbled gray without an iota of detail, & the remaining 2 days wholly invisible, the more that as it is to be a portrait I can give way to no remedies of imagination. What is more odious to me than all is the absence of nice walks:- all high dusty roads, & that for miles in all directions. I have 2 very goodsized and crumbfortable rooms enough, only the situation of the place & its noise make it a perfect prison to me, & give my natural disposition for grumbling great scope.

When you write – say particularly how you get on, & when you think of beginning the next picture.

Observe the Lovers’ seat on the opposite page. By jingo wet as it was, I wish we were at old Mrs Neeve’s again, cadmium & black beetles included!

If you write to the north – remember me to Uncle Millais. Goodbye, daddy.

Was the noise Lear complained of that of drinkers or horse-drawn traffic outside? (Today’s visitor to the Prince Albert, listening to planes and lorries, may feel he had little to complain of.) The reference to dusty roads reminds us of their unpleasant state before tarmac, but with the Great Park so close nothing

shows more clearly Lear’s pig-headed determination to be miserable than his statement that there are no “nice walks” to be found. Moreover the estate of St Leonard’s Hill was famed for its beauty: in 1792 Dorothy Wordsworth, sister of the poet, had visited it and in very different mood written:

It is in the finest Situation that can be conceived. It stands upon an Eminence, and commands a noble View of Windsor Castle and of hills richly wooded. This view and a thousand others in the Park and Forest are a thousand Times superior to that from the Terrace [of the Castle]. (5)

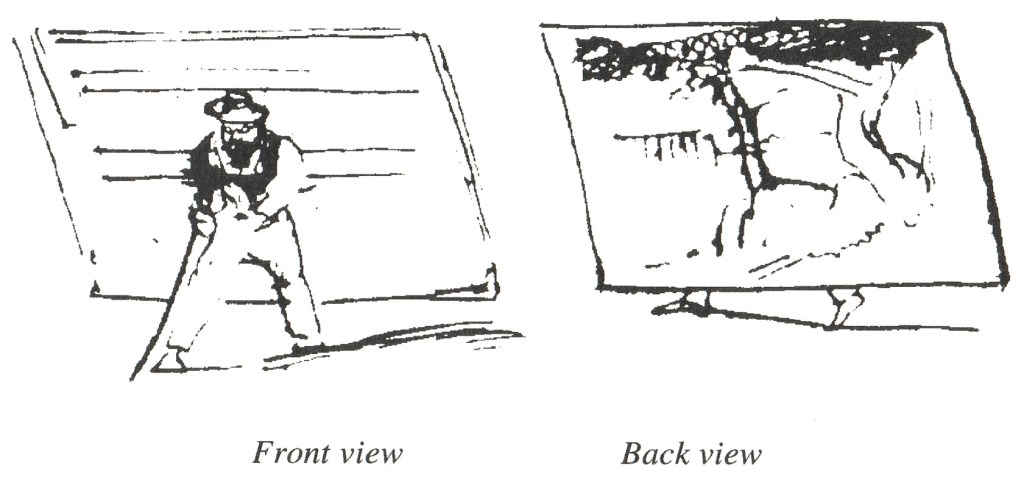

Perhaps Lear felt peeved that he hadn’t been invited to stay at the house, but the Derby family had come to consider Lear a bit of a scrounger and probably the Earl thought he was already doing him a good enough turn in giving him the commission. Presumably he was at least able to leave his painting at the house somewhere: lugging an eight-foot canvas up and down the hill – as he illustrates with another painting – would really have given him something to moan about.

After he left Clewer, Lear went off to Sussex to find some sheep to paint, truth-to-nature style, in the foreground. Not surprisingly they caused problems and, still grumbling though more light-heartedly, he wrote first to Lord Derby:

Infinite obstacles owing to the size of the picture, the shearing of the sheep, the growth of the lambs &c &c &c &c &c &c, have at last worn me out utterly

And then to Hunt:

The sheep here are all lame, and entirely driven away. So I shall put in a drove of Apes from the Zoological Society. Had he been working more recently he could have found a troop of baboons nearby at the Safari Park: they’d have given him a great deal more trouble than sheep.

Nevertheless the picture was finished, and was exhibited in London in 1855. Lear was delighted with its reception and wrote triumphantly to Lord Derby that:

the picture has literally the best place in the whole exhibition… And the opinions I have from artists whose opinions are valuable to me, are most satisfactory and encouraging.”

By then however Lear had decided that absolute fidelity to nature was not for him and he went back to studio painting. But the affection and respect he felt for his friend and father-figure, “Daddy” Hunt, remained with him for the rest of his life.

Hester Davenport

Notes

* The letter is in the possession of the Huntington Library, California, by whose kind permission it is printed here in its entirety for the first time.

1. Lear refers to ‘The Light of the World’ (now in the Chapel of Keble College, Oxford): the “breast-plate” is the jewelled clasp of Christ’s robe. It is based on part of the costume of a High Priest, illustrated in an engraving in Hunt’s Bible, and is rich in symbolic significance.

2. Hunt’s wealthy uncle, William Hobman, lived at Worcester Park Farm, Esher. His parents named him after his uncle, but the name Hobman was misspelt Holman on the baptismal certificate and Hunt insisted on using it.

3. Millais had gone to Scotland with the PRB champion John Ruskin and his wife Effie. Lear makes an innocent little query about an expedition whose consequences were to set tongues wagging; on their return Effie left her husband and the marriage was annulled for non- consummation. In 1855 she married Millais.

4. “Naughtybiography” is another example of Lear’s enjoyment of word play. Benjamin Haydon (1786-1846) was a west country artist, best-known for his large historical and Biblical paintings, who in a fit of despair committed suicide. For all the pleasure he got out of the Journals, including anecdotes at Sir Sloshua’s expense, Lear’s own melancholy may well have been increased by thoughts of Haydon’s death. David Wilkie, a Scottish artist, was Haydon’s friend. Tom Taylor was an art critic and dramatist (one play, Herne the Hunter, was based on Harrison Ainsworth’s Windsor Castle).

5. The present whereabouts of the painting is not known.

References

AMOR, Anne Clark, William Holman Hunt: The True Pre-Raphaelite, London 1989

CHITTY, Susan, That Singular Person Called Lear, London 1988

MAAS, Jeremy, Holman Hunt and the Light of the World, London 1984

NOAKES, Vivien, Edward Lear: The Life of a Wanderer (revised edition), London 1979

NOAKES, Vivien, Edward Lear 1812-1888 at the Royal Academy of Arts, London 1985

NOAKES, Vivien, Edward Lear: Selected Letters, Oxford 1988

ROONEY, Sheila and Pat, St Leonard’s Hill, Windsor: House, Hermitage, and Hill, Windsor 1991

de SELINCOURT, Ernest, The Early Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth, Oxford 1935

WINDSOR LOCAL HISTORY PUBLICATIONS GROUP, The Streets of Windsor and Eton, Windsor 1988.