– a Family Business

Published in Windlesora 09 (1990)

© WLHG

In June 1801 the following short obituary appeared in the Gentleman’s Magazine: :

‘At Clewer, near Windsor, aged 80, Mr John Davis, who, with his father and grandfather were successively locksmiths to the crowned heads of this realm for more than 150 years.’

John Davis had been living in retirement at Nightingale Place, Clewer, a small estate in Hatch Lane which had been left to him by his father. He had already, some four years previously, handed over the business to his youngest son George. The funeral that took place on Wednesday 3rd June at St Andrew’s Church had been a private affair, for in his will he had asked that only his relatives and workmen should attend. He had also requested to be buried in a vault to be made close to his pew in the church.

John Davis’ father and grandfather had also been named John and, not surprisingly, in later years this led to a certain amount of confusion. In some cases their works became wrongly attributed. To help clarify the situation Fig 1 shows four generations of the Davis family that built up a highly successful smith’s business in Windsor throughout the eighteenth century. As well as being locksmiths, they were called on to work as blacksmiths, ironmongers, clockmakers, and bell hangers. The family produced some exceptionally gifted craftsmen and the extent and variety of their work is perhaps not as fully appreciated today as it might be.

To most people the name of John Davis is only associated with the chiming clock in the Curfew Tower of Windsor Castle. The first John Davis was, indeed, the maker of this clock in 1689. Very little is known about the early part of his career. He is said to have been the son of William Davis, the King’s blacksmith in Windsor, in which case he would have become familiar with all the skills needed to work in iron. However, at some stage he must also have been trained in the art of clockmaking and particularly in the use of brass. Examples of his longcase clocks and brass lantern clocks show a quality equal to that of many of the best London makers. He was equally skilful in the making of turret clocks. Four apprentices trained under him including his own son in 1705. He died in 1713, leaving a house in Thames Street to his daughter and the adjoining house together with the business to his only son John.

After the young John Davis, aged only twenty two and barely out of his apprenticeship, had taken over the business very little is known about him for nearly ten years. He was, however, to become the most successful member of this family and it is worth looking closer at some of his achievements whose varied nature is typical of work done by the Davis family over the next one hundred years.

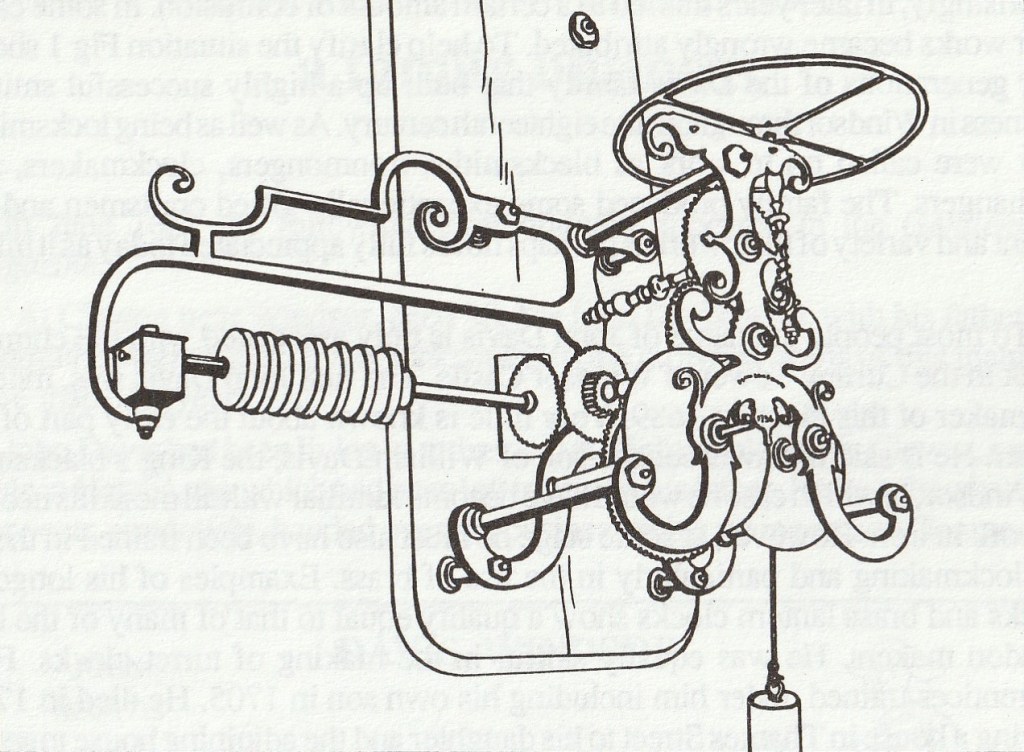

In 1722, he commenced a long association with Eton College carrying out works that perfectly illustrate this variety. To begin with, he maintained the clock in School Yard for over forty years. Between 1725 and 1729, when the College Library was being built, he supplied a large amount of the iron work, over eight tons of it, needed for structural work, gates, and banisters etc. He then supplied interior fittings such as brass grilles for the manuscript cupboards and over 65 brass locks. His bill specifies that all these locks were ‘home made’. Some years later Davis was called on to do work in the kitchens, such as mending the beam scales in the buttery and repairing the stoves. One of the most decorative examples of wrought iron work made by Davis at this period was a magnificent weight-driven clockwork roasting jack. Made in 1736, it was mounted up on the wall to one side of the open fire in the kitchen, and could drive up to six roasting spits. This jack remained in continuous use until the 1920’s.

In about 1730 John Davis became involved in an entirely different project. The town of Windsor was having problems with its water supply. Daniel Beaumont, who leased the Waterworks at the time, was providing an increasingly unreliable service, much to the concern of the Council, who were faced with complaints from customers and were themselves especially worried about the lack of water in case of a serious fire in the town. The Minute Books of the Council record their desperate pleas for anyone to come forward with a solution to the problem. Davis, in partnership with Benjamin Crompton, accepted the challenge for in about 1732 he took over the lease of the Waterworks. Later, Joseph Benwell became his partner, and the Davis family retained an interest in the Engine and Waterworks until near the end of the eighteenth century.

One of his apprentices was his own son John, in 1736, and to distinguish these two, the father was then referred to as Davis the elder or senior and the son as Davis junior.

It was as a clockmaker, however, that John Davis senior excelled. For many years he was listed in Court Registers as ‘Clockmaker to King George II’ or ‘Clockmaker & Blacksmith to HM Board of Works at Windsor Castle’. He supplied his customers with longcase clocks, bracket clocks and the occasional

tavern clock. As a maker of turret clocks, however, his services became much in demand. By careful attention to the details necessary for accurate and reliable timekeeping, Davis produced turret clocks of high quality. This was a time of increasing prosperity in England and the wealthy landowners were enlarging or building impressive country homes on their estates. The classic style of the accompanying stable blocks that became popular featured a central arch surmounted by a turret for a clock. The stables at Baylis House, Slough had the earliest known turret clock by Davis senior, dated 1735. The gardens of the same house also had a sundial signed ‘J. Davis Windsor 1744’. Several estates along the old Forest Road and in the Great Park had clocks supplied by Davis: the stables at Bill Hill for Lord Gower in 1749, at Great Lodge for the Duke of Cumberland in 1750, at St Leonard’s for Lilley Aynescombe in 1752, and at Billingbear Park in 1757. His reputation soon spread to other counties and his clocks, some in churches, are found in Wiltshire, Buckinghamshire, Oxfordshire, Hampshire and as far west as Somerset, for Lord Iichester at Redlynch Park, near Wincanton, in 1743. The recommendation for this may have come from Lord Ilchester’s brother, Henry Fox (later created Baron Holland), who was then Member of Parliament for Windsor. Even in London, Davis supplied a striking clock for Greenwich Hospital Chapel in 1754. Unfortunately this was destroyed twenty five years later in a disastrous fire.

No portraits of John Davis senior are known but he is included in a pen-and- watercolour drawing by Paul Sandby done about 1758 in which four men are shown: Isherwood the brewer, Capt Archibald Campbell, Davis the smith and a younger, unnamed man standing close to Davis. This may well have been Davis junior, who would have been in his mid thirties at the time.

John Davis senior died in 1762, a wealthy man, and passed on to his son the fruits of his success:

- A house and shop in Thames St in the Castle Ditch.

- A house adjoining the above.

- A house and stable in George St. Houses in Peascod St & Tull Lane called ‘The Pestel & Mortar’.

- Several freeholds in the Parish of Clewer.

- Copyhold estate purchased from Robert Lovell.

- Copyhold estate purchased from George Rosewell.

- Copyhold estates in the parishes of Taplow & Hitcham. The Rights & Title of the Engine & Waterworks.

John Davis junior, having worked with his father for over twenty five years, would have experienced few problems on taking over the business. Domestic clocks were still made by him but only three turret clocks are known, the last being for George Vansittart at Bisham Abbey in 1783. He continued with his interest in the Waterworks, and in 1769, partnered by Roger Cutler, a plumber from Eton, he made several improvements. They fitted a larger water wheel to the Engine to provide more power to pump water to the top of the town and the Castle. They also proposed to replace some of the old mains. Soon after 1790 Davis appears to have sold his interest, and the Cutler family remained proprietors of the Waterworks until 1888.

In 1776 he received the Royal Warrant as ‘Locksmith in Ordinary to His Majesty’s Palace of Windsor Castle’. In this capacity he serviced all the locks in the Castle and supplied new ones when necessary. By 1797, when he was 75 years old, he began handing over the business to the next generation by making his youngest son George a co-partner. The following year he resigned the Royal Warrant in his son’s favour.

The funeral in 1801 would have been attended by John Davis’ two surviving sons, Richard and George. Both had been apprenticed to their father, but Richard seems to have left the business and little is known about him, except that he outlived his father by only a few years and died in 1804.

One member of the family not directly concerned with the business is, however, worthy of special mention here. Henry Edwards Davis, brother of Richard and George, was sent by his father to be educated at a school in Ealing. Later he entered Balliol College, Oxford, graduating asa B.A. in 1778 and as an M.A. in 1780. He soon made a name for himself by making a public attack on part of the first volume of Henry Gibbon’s work The Decline and fall of the Roman Empire which was published in 1776. Henry Davis published his Examination of the 15th and 16th chapters in 1778. It was these two chapters that dealt with Christianity to which he objected. Davis was not the only critic but Gibbon’s famous Vindication was chiefly directed against him and Gibbon states that Davis was rewarded for the attack by a ‘Royal pension’. He took Holy Orders in 1780 and became Fellow and Tutor at Balliol. Sadly, his health broke down, and after a lingering illness he died in 1784, aged only twenty seven. He was buried at Windsor and a memorial to him was erected in the Parish Church.

George as we have seen, continued in the business and was to achieve more fame as a locksmith than any of them. In 1799 he took out a Patent for a ‘A double chambered lock with cylinders, to which pins are attached in different directions instead of wards’. His invention was considered sufficiently secure for the locks to be used on Government despatch boxes. These locks were extremely well made and the backs were engraved with the names of the various departments using them: the Colonial Office, Irish Office, etc., and the illustration (fig. 5) shows a typical Davis lock, in this case used by the Home Department, Whitehall. To protect this security and to discourage unauthorised locksmiths from making keys, a message was engraved on an inner plate of the lock offering a large reward of £20 or even £50. On one occasion, in 1815, a £20 reward was paid to a locksmith in Wolverhampton by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nicholas Vansittart. At the same time he offered a further £100 for the name of the person trying to have the key made.

King George III frequently called on the tradesmen in the town and one day, according to Price in his Treatise on locks and keys (1856), he paid a visit to George Davis in his workshop and offered to confer on him the honour of a knighthood, which George Davis humbly and respectfully declined, saying to his Majesty:- ‘Sire, it would sound very odd, were I to meet a gentleman in the street, and he were to say “Sir George Davis, please to come and mend my smoke-jack”. ‘ This reference to a smoke-jack, another form of roasting jack driven by a vane inside the chimney turned by the rising hot air, indicates that supplying and servicing these jacks still formed part of the business.

All of the Davis family so far mentioned, apart from Henry, had taken an active part on the Town Council, but George was the only one to become Mayor of Windsor, in October 1819. His portrait hangs in the Mayor’s Parlour in the Guildhall and he is portrayed wearing the gold chain of office that was presented on behalf of King George I’V in 1820. At the start of the new reign George Davis’ warrant was renewed as ‘Locksmith and Ironmonger in Ordinary to his Majesty.’

After his term of office as Mayor and a further term as Justice of the Peace, George, by then 62 years old, turned his thoughts to retirement at his farm at Nightingale Place. At about this time the business seems finally to have passed out of the Davis family as evidence suggests that one of George Davis’ workmen, William Berridge, may have gone into partnership with and then taken over from him. A trade directory of 1824 lists Berridge as Ironmonger in Thames Street but makes no mention of Davis. Berridge moved from the Castle Ditch in 1830 and setup his ironmonger’s shop and foundry at the corner of the High Street and Sheet Street. The works were at the back with an entrance from Bachelors Acre and from there William Berridge and his son, for another twenty years or more, continued the tradition of high quality craftsmanship started by the Davis family nearly two hundred years earlier.

Many of the properties associated with the Davis family have long since disappeared. The house and stables in George Street made way for the new railway station in 1849. The shop and houses in Thames Street were cleared away with all the other buildings in the Castle Ditch in 1851. Nightingale Place was, for a short while, a school for boys before becoming home for the Clewer House of Mercy and was finally demolished in 1854 to make way for the present Convent buildings. Any memorials that may have been erected in the Parish Church were lost when the Church was rebuilt in 1822 and no gravestones have survived. What do remain, however, in and around Windsor, as a lasting memorial to the Davis family are the many examples of their skill as craftsmen.

Peter Ashworth