Published in Windlesora 06 (1987)

© WLHG

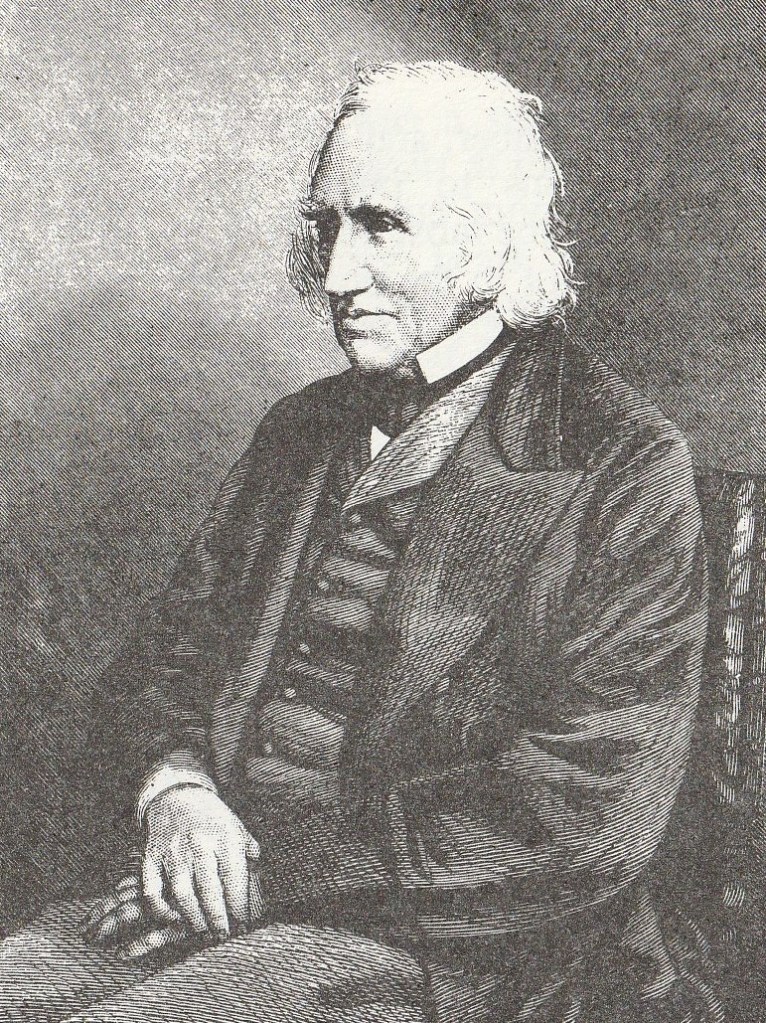

Among the three or more million annual visitors to Windsor, a great number often pause by the statue of Queen Victoria on Castle Hill to photograph the imposing Henry VIII Gateway and entrance to the Castle. How many, when also photographing the statue which imperiously surveys Peascod Street, will further enquire into the plaque above No.2 Castle Hill, and included in countless photographs throughout the world. This simple plaque records the birthplace and book-shop of Charles Knight and is inscribed ‘Charles Knight 1791- 1873 Author and Publisher lived here.’

To many Windsorians Charles Knight is best remembered as the founder in 1812, with his father, of the Windsor and Eton Express; but to many in the world of publishing and bookselling he is recognised as one of the most enterprising publishers of the nineteenth century, a pioneer in popular literature and a man who made important contributions to public education and publishing techniques. His career in publishing was long and varied, but it is for his association with the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge founded by Lord Brougham and others in 1826 that he is best remembered, for it was the SDUK with The Penny Magazine, Penny Encyclopaedia, and Library of Entertaining Knowledge, etc., which went further than ever before in bringing reading to the masses, and can be said to be the forerunner of book clubs and paperbacks. Being a man with a gift of expressing himself in words which few could equal in his time, and despite his very busy publishing activities, he still found time to write many books and plays, and also at one period in his life acted on the London stage with such notable figures as George Cruikshank, Wilkie Collins and Charles Dickens, who was numbered among his friends.

Charles Knight’s father (Charles Knight Snr) was established as a bookseller and printer at No. 2 Castle Hill (or Castle Street as it was then known) by 1780, and quickly assumed a position of some importance in Windsor, chiefly through his association with the Microcosm, a paper written by Etonians such as Canning (later to be Prime Minister) and Hookham Frere, and published at 2 Castle Hill. Charles Knight Snr, twice Mayor of the Borough of New Windsor in 1806 and 1817, married the daughter of a wealthy yeoman of Iver and their only son, also to be named Charles, was born on March 15 1791. After only a very short married life together, in fact when Charles Knight Jnr was only two years old, ‘this most amiable woman’ died and the boy was subsequently brought up by his father. Apart from being a successful bookseller and printer, Charles Knight Snr also had a leaning towards writing, and the fact that he was a very learned and scholarly man is evident in the first Windsor Guide which was compiled and published by him in Windsor on March 31, 1785 and ran into many editions over the next 50 years.

George III and Queen Charlotte were familiar figures to the local tradespeople, and were frequently to be seen wandering around the town, acknowledging many of the local traders by name. Charles Knight recalls in his autobiography Passages from a Working Life an amusing incident soon after the publication of Paine’s The Rights of Man in 1791 when the King was wandering about Windsor early on a summer morning and was heard calling out, “Knight, Knight in the bookshop” which had just opened. Charles Knight Snr made his appearance at the sound of the well-known voice and found the King reading The Rights of Man which had arrived with other books on the previous evening in a parcel from Paternoster Row.

Living surrounded by books Charles learned to read at an early age, and he considered later in life that this had much to do with rendering his constitution weak and feeble. Despite the loss of his mother, the young Charles Knight spent a very happy childhood in Windsor, roaming the Castle and playing with his friends in the quadrangle and terraces. After attending day school in Windsor, he was in 1803 sent to the school of Dr Nicholas in Ealing, where he concentrated on classical studies. During school holidays at this time he found patriotic feeling running very high in Windsor, for these were the days of the Napoleonic Wars, and his father was a lieutenant in the local Volunteer Corps. At the age of fourteen he signed indentures of apprenticeship to his father, and this began his life’s work in publishing and bookselling. Apart from selling new books, his father also dealt in secondhand and antiquarian books, attending auctions and buying private libraries. This side of the business greatly appealed to the young Charles Knight and he soon acquired a very sound knowledge of the book trade, and his bibliographical background was to stand him in good stead when he became associated with the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. In his autobiography Knight tells of a few happy weeks in 1811 spent at Cliveden cataloguing in the library of the Countess of Orkney. During this period the social inequality of the time began to have a great effect on him, and the misery of the poor in his native town is vividly described in his writings, for although Knight loved Windsor, he was often critical of the pomp surrounding the Castle. From about this time he became convinced that social reform would only come from education, and that the key was cheap books.

His ambition to bring good books within the reach of all led him in 1810 to form a local Reading Society, but this was short-lived mainly because it attracted members from the more prosperous middle class, and to quote from his autobiography, “the age of mechanics’ institutes was still far off”. The opinion of the great majority was against adult education. For the working class to read books was to make them dangerous members of society. Some 23 years later when he was invited by Sir John Herschel, the astronomer and President of the then thriving Windsor and Eton Public Library, to address the members, he was able to report considerable progress in both his own career and the diffusion of knowledge. In 1812, on gaining his majority, he went to London for a few weeks to undergo a spell of training in the offices of the Globe newspaper, in order to learn the work of a journalist. He frequently found himself in the House of Commons and was appalled at the conditions under which reporters had to work. Having completed this brief introduction to the newspaper world, and having long desired to possess a paper of his own, he realised this ambition when, on August 1, 1812, in conjunction with his father, he started the Windsor and Eton Express, the editorship of which he continued until 1827.

During 1814 Knight married Sally Vinicombe, the daughter of an architect, and she was to have a strong influence on his life. In this period many people looked upon newspapers as being the poor man’s Book of Knowledge, and Charles Knight used the medium of his newspaper to promote his views on popular education; his first article in popular literature appeared in the Windsor and Eton Express on December 11, 1819 entitled ‘Cheap Publications’. Soon afterwards, in collaboration with H.E.Locker, he founded the periodical The Plain Englishman, which only lasted from 1820-22. But it was an article headed ‘Diffusion of Useful Knowledge’ which shows the way his mind was turning.

During 1820 Knight became editor and part owner of the weekly London paper The Guardian, and in addition was publisher of The Etonian, thus dividing his time between Windsor and London. Out of The Etonian was born Knight’s Quarterly Magazine which boasted such contributors as Praed, De Quincey and Macaulay; but despite being praised in many quarters, it failed after only a few issues, mainly due to differences of opinion among the contributors.

In 1824 Charles Knight’s father died, and soon afterwards Knight moved much of his business to London, where he had opened an office in Pall Mall East, and began a modest publishing programme. Knight’s great ambition was to publish popular literature at a price the masses could afford, and thereby cater for the demand from the greatly increased reading public which, it has been estimated, increased from 1) million to 7 million between 1780 and 1825, and was now being increased still further by the rapid spread of adult education with the founding of Societies and Mechanics’ Institutes. Beginning in Scotland with Dr Birkbeck, Mechanics’ Institutes were helped to spread in England by the genius of Henry Brougham. Tn 1895 it looked as though Knight’s ambition was about to be achieved in what would have been a forerunner of the SDUK, but plans for a ‘National Library’ were abandoned when Knight experienced financial difficulties, and the Library was finally taken over by John Murray. Henry Brougham, having heard of Knight’s proposed National Library, and having in the same year announced his own plans of an educational publishing programme, approached Knight through the good offices of a mutual friend, Matthew Davenport Hill, and in July 1827 Charles Knight was appointed superintendent of publications for the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. This was the turning point in Knight’s career, and over the next 20 years he made many notable contributions to public education and publishing technique. Not only was it the most interesting period in his life, but it also marked a turning point in the political and social history of the country, being a period of great progress in the education of the people.

The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge pioneered the idea of publishing works of information in weekly numbers and in book form; it was formed in 1826 by Henry Brougham, one of the leading reformers of the early nineteenth century. He was also an MP and Lord Chancellor for four years, in Lord Melboune’s administration. Born in 1788 in Edinburgh, Henry Peter Brougham completed his education at Edinburgh University, where he read law, and in 1802 was a founder of the Edinburgh Review, but it was the publication of his famous pamphlet Practical Observations upon the education of the people addressed to the working classes and their employers, in 1825 which led to the formation of the SDUK. Having been long associated with Birkbeck, the founder of Mechanics’ Institutes, he helped to found the London Mechanics’ Institute and in 1828 founded London University.

In his early days with the SDUK, Charles Knight visited Reading Institutes in many parts of the country, speaking on behalf of the SDUK. I have a copy of his address to the Windsor and Eton Reading Society delivered at the Windsor Guildhall on October 19, 1833.

The publishing programme of the SDUK, which began in 1827 with the launching of the Library of Useful Knowledge, is too vast to discuss in detail, but there were many highlights over the next 20 years and Charles Knight was heavily involved in most of these ventures. One of his first series for the SDUK was the British Almanac which appeared in 1828 and continued under his editorship until 1873. There was also a Companion to the Almanac, and other Year Books which included the British Household Almanac, Working Man’s Almanac and Working Man’s Year Book. In April 1829 there appeared the first volume of the Library of Entertaining Knowledge of which Knight was the editor. The series covered such subjects as History, Geography, Natural History, Biography and the Arts, and was tastefully illustrated by woodcuts.

One of the greatest achievements of the SDUK was undoubtedly the success of the Penny Magazine which was launched on March 31 1832, and went further than ever before in bringing regular reading matter to the masses at the amazing price of 1d per week or the monthly issue at 6d. Its success was a surprise even to the editor Charles Knight, who was able to report at the end of the first year a sale of 200,000 copies in weekly and monthly parts, representing probably a million readers. Forty years previously Burke had estimated the number of readers in the country as 80,000. In the Penny Magazine, Charles Knight paid particular attention to the effective use of illustrations, and a great deal of the success was due to the extensive use of the woodcut. Eminent artists were engaged both as draughtsmen and wood engravers, and by means of this revived art Knight can be said to have diffused popular art as well as popular literature. The Penny Magazine lasted for 14 years and in 1846, when the SDUK ceased its publishing programmes, it was continued by Knight and the title changed to Knight’s Penny Magazine.

The Penny Encyclopaedia was launched in 1833 as a result of the success of the Penny Magazine and was suggested by Charles Knight. It was originally intended to be a work of eight volumes, and was completed in 1846. The work was originally issued at 1d per number each week, but gradually increased in size and price until it was sold only in monthly parts at 1s.6d. Although run at a loss, it was perhaps the most prestigious of all the SDUK publications and a great publishing triumph. Charles Knight tells us in his autobiography that on its completion the contributors gave a banquet in his honour, and that this was the proudest moment of his life.

Charles Knight could not afford to take part in the next and grandest venture of the SDUK which ultimately led to the demise of the Society. This was the New Biographical Dictionary, which was intended to supersede anything of a similar nature previously attempted, but after letter ‘A’ was completed, the Committee found to its horror that seven half volumes had been filled and a loss of £5,000 incurred. This was bad enough but when contributors were asked to send in suggestions for the letter ‘B’, one man alone forwarded more than 2,000 names. The Society had by now exhausted its available funds, and in view of these bleak prospects quietly retired from the publishing scene; as Charles Knight said, “The Society’s work is done for the greatest object is achieved, fully, fairly and permanently. The public is supplied with cheap and good literature to an extent which the most sanguine friend of human improvement could not in 1826 have hoped to have witnessed in 20 years”.

During the entire period of his association with the SDUK Knight continued to publish in his own right, and some of his most successful works appeared during these 20 years, including the Pictorial Bible,

Pictorial History and The Illustrated London. One of Knight’s aims was to produce coloured plates cheaply for the masses, and the results of his experiments in this field are best seen in Old England issued in 96 parts between 1844 and 1845 and England’s Worthies published in 1847. These were the first printed colour plates produced for the popular market.

The writings of Charles Knight are too numerous to list, but mention must be made of his Half Hours with the Best Authors, which achieved world-wide popularity, and Passages from a Working Life During Half a Century (in three volumes), his most interesting autobiography and an invaluable commentary on social, political and economic life in nineteenth century England.

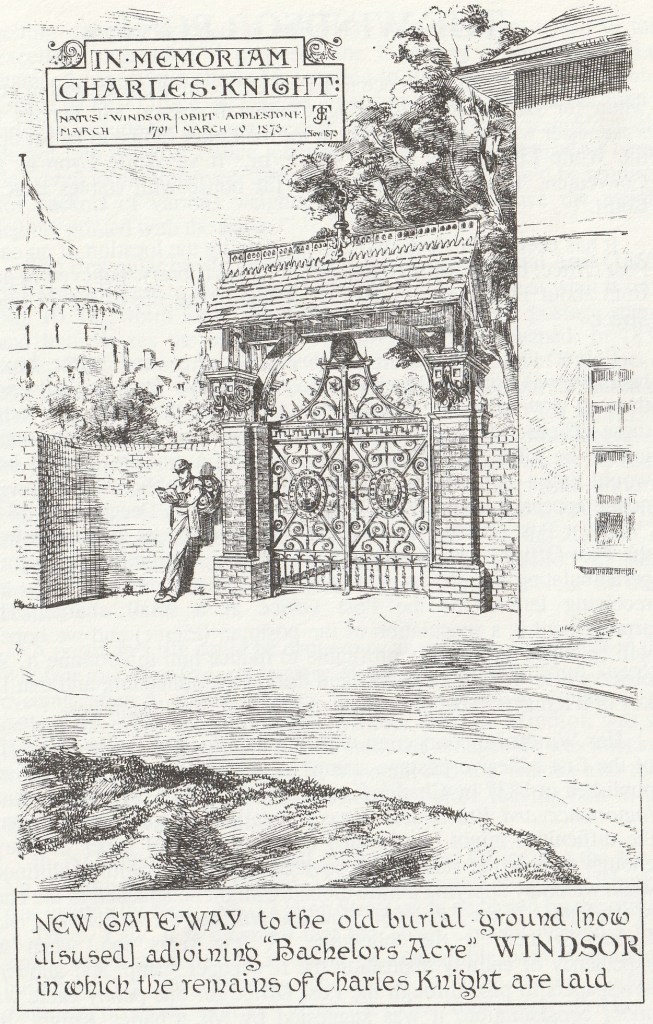

Charles Knight died at Addlestone in Surrey on March 9, 1873 aged 81, and was buried in the family vault in the cemetery* above Bachelors’ Acre at Windsor. The contemporary newspapers were full of tributes to his memory, and a committee of leading authors and publishers was formed for the purpose of perpetuating his memory in the form of a marble bust. This sculpture was presented to the Corporation of Windsor on June 14 1875 and placed on a pedestal in the Council Chamber of the Guildhall. The inscription reads as follows:

‘Charles Knight, author and publisher, born in Windsor March 15 1791, died at Addlestone Surrey March 9 1873, and buried in his native town. His chief work through life was to bring good literature within the reach of all. This bust was presented to the Corporation of Windsor by the committee of the Charles Knight Testimonial June 14 1875’.

David Hedges

* Editor’s Note: It has been suggested that this burial ground could become a car park in the near future for the Castle Hotel.